By clicking on the blue portal below, you can download a PDF of the July 28 edition of the San Bernardino County Sentinel.

Monthly Archives: July 2017

SBC Democratic Party Chairman Removed Through Parliamentary Jujitsu

By Mark Gutglueck

SAN BERNARDINO (July 28)–Members of the San Bernardino County Democratic Central Committee last night took action to remove their chairman, Chris Robles, as a member of the central committee, which they maintain has the effect of removing him from his chairmanship.

Robles, however, says the ploy used to remove him was a rogue one that has no practical or official meaning, and that he remains as the leader of the Democratic Party in San Bernardino County.

It appears that Robles, who for more than three months was able to stave off a vote to remove him through the use of parliamentary procedure, ironically was ultimately removed through the utilization of the same parliamentary procedure when he adjourned the meeting but failed to properly process a vote to confirm the adjournment. This permitted those who had for so long been frustrated by his parliamentary maneuvering to themselves reconvene the meeting in his absence and hold the vote that resulted in his expulsion.

Discontent with Robles’ leadership of the county party apparatus has been growing for some time.

When he first transplanted to San Bernardino County in 2012 after working as a Democratic Party operative in Los Angeles County, he was embraced by many local Democratic Party activists. He worked professionally as a political consultant, and it was widely believed that his command of electioneering tactics would be turned to the party’s advantage.

The need to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of Democratic Party operations was manifestly clear. In 2010, after decades of San Bernardino County being under the rock solid control of Republicans, the number of voters registered countywide as Democrats eclipsed the number registered as Republicans. Despite that, the Republican Party in San Bernardino County continued to maintain the upper hand, as Republicans held on to more than 60 percent of the political positions throughout San Bernardino County, including federal, state, county and municipal offices. Consistently, registered Republicans showed up at the polls or participated by mail-in ballots at a percentage significantly greater than did their registered Democratic counterparts. In 2012, 2014 and again in 2016, Republicans continued to dominate the majority of political offices at nearly all levels throughout the county, despite the Democrats having significant and even overwhelmingly superior registration numbers in many of the voting districts where those Republicans yet hold office.

At present, the registration gap between Democratic and Republican voters has grown to 8.5 percent of the county’s electorate, as 360,030, or 40.2 percent of the county’s 895,395 total registered voters are identified as Democrats and 283,494, or 31.7 percent affiliate with the Republican Party.

Three of the five members of the county board of supervisors are Republicans; two of the county’s five Congress members are Republicans, with two of the Democratic Congress members having districts in which those portions outside San Bernardino County are overwhelmingly Democratic; three of the county’s four state senators are Republicans; five of the county’s eight members of the California Assembly are Republicans; and 17 of the county’s 24 cities have city councils composed of a majority of Republicans. Where the Democrats hold state or federal office in San Bernardino County, they hold a commanding registration advantage. In those electoral jurisdictions where the Democrats have close to parity with the Republicans or hold a lead that is substantial but less than entirely overwhelming, they have consistently lost to Republicans. Such is the case in the 40th Assembly District where registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans 91,615 or 40.4 percent to 76,234 or 33.7 percent, and a Republican, Marc Steinorth, holds office. In San Bernardino County’s Fourth Supervisorial District, where the registration numbers are lopsidedly in favor of the Democrats 71,859 or 43.1 percent to 47,128 or 28.3 percent, a Republican, Curt Hagman is in office, even though his opponent in the 2014 election was a then-incumbent Democratic U.S. Congresswoman, Gloria Negrete-McLeod.

Two months ago, a contingent of Democrats initiated an effort to remove Robles as central committee chairman, when more than 30 advocates for his removal showed up at the May 25 meeting of the Democratic Central Committee, intent on lodging a vote of no confidence against him. Robles, however, used his control of the proceedings to refuse to recognize the call for a vote of no confidence. He then stood down repeated and heated calls for a vote to be put to the entirety of the central committee with regard to effectuating his removal, doing so by simply pronouncing them as out of order. He utilized one of his primary allies within the central committee, Mark Westwood, to stave off further calls against him, surrendering chairmanship of the proceedings to Westwood. Westwood, who was not elected to the central committee in his own right but was appointed as an alternate to Rita Ramirez-Dean, an ex officio member of the central committee. An ex officio member is one accorded central committee membership by virtue of having represented the Democratic Party as a candidate in the most recent general election. In 2016 Ramirez-Dean unsuccessfully vied for Congress against Republican Paul Cook in California’s 8th Congressional District. Robles appointed Westwood to the executive committee of the central committee, a group of eight officials vested with decision-making authority with regard to a bevy of party issues. A bear of a man at 6-foot and 5 inches and well over 300 pounds, Westwood has exhibited extreme loyalty to Robles. Westwood twice ruled out of order calls for votes of no confidence against Robles that had been seconded.

At the June 22 San Bernardino County Democratic Central Committee meeting, Robles was again confronted by a substantial number of committee members intent on initiating a review of what they maintain was Robles’ violation of a key bylaw alleged to provide grounds for his removal from the central committee: advocacy work he had done through his campaign consulting company, Vantage Campaigns, for a Republican, Gus Skropos, who had vied for the Ontario City Council in the 2016 election. Those calling for Robles’ ouster were armed with a California Form 460 campaign financing disclosure document filed by the Skropos campaign with the Ontario city clerk’s office on July 20, 2016 showing it had paid $1,850 to Vantage Campaigns and another Form 460 filed with the Ontario city clerk’s office on January 31, 2017 showing the Skropos campaign had paid $6,147 to Vantage Campaigns for “consulting.” They also put on display an email from Skropos sent on September 13, 2016 to Laurie Stalnaker, who in addition to being on the Democratic Central Committee is also involved with the AFL-CIO. In that email, Skropos sought the AFL-CIO endorsement in his run for city council, and stated, “My consultant is Chris Robles, should you wish to work with him.”

Robles denied working for Skropos, insisting that Sam Crowe, a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat who had been on the Ontario City Council 50 years ago and had later been the Ontario city attorney when Skropos was on the Ontario City Council in the 1980s and mayor in the 1990s, had chosen to run on a ticket with Skropos in 2016. His work had been on behalf of Crowe, Robles insisted, which inadvertently brought him into the Skropos political camp. His critics, citing the Form 460s, would have none of it and pressed again to have Robles removed. Robles was able to use his position of being in control of the meeting, as well as interpretations of the committee’s bylaws provided by the parliamentarian Robles had appointed, Carol Robb, to maneuver out from underneath the onus of the attack against him. But because of the continuous back and forth between Robles and his detractors, virtually nothing on the committee’s June 22 agenda was approved that evening. And to alleviate the situation, either Robles or one of his supporters phoned the police, whose arrival was used as a pretext to adjourn the meeting.

Last night, July 28, Robles was again confronted by committee members seeking to effectuate his removal or resignation. After the meeting was initiated, several members sought to add items to the evening’s agenda, two pertaining to “removal of a member” which Robles resisted, calling them out of order on the basis of procedural error. This provoked numerous objections and calls for points of order which Robles rejected, again relying upon Robb for support. There were further points of order with an appeal that Robb read from the rules and bylaws. Having partially worked through the agenda addition requests but before considering any actual agenda items, Robles eighteen minutes into the proceedings adjourned the meeting, having wearied of having to respond to his critics’ carping upon what they insisted were his unforgivable shortcomings.

He momentarily left the podium but returned when protests were heard that there had been no actual motion for adjournment, nor a vote on such. Robles requested a vote, calling for ayes. Upon hearing a half dozen or so ayes, he declared the meeting concluded without calling for those opposed to register their position on the adjournment. He disconnected the cord to the podium microphone, during which a series of shouts calling upon Robles to ask for “no” votes on the adjournment can be heard on the recordings of the meeting. Robles, with several of his supporters, including Mark Westwood and Sam Crowe, then took his leave of the room, prompting a loud round of applause, which is audible on the recordings of the meeting. Prior to exiting, Robles instructed sergeant-at-arms Sean Houle to call the police.

With most of those in the contingent opposed to Robles yet in the room, a member announced that the meeting had not been properly adjourned as another member promptly began calling the roll by California Assembly district. As the roll call was proceeding and Ron Cohen, one of two members of the executive committee who is not closely affiliated with Robles and the senior member of the executive committee present, was in the process of reconvening the meeting, the police arrived. Cohen entrusted the conducting of the proceedings to the other member of the executive committee there, Jim Gallagher, while he dealt with the police. Gallagher proceeded with the motions to amend the agenda. Cohen explained to the police that there was a quorum of the committee present and that party business was being conducted. The police allowed the proceedings to continue, but remained present to ensure order. A tally was taken and it was determined that there was a quorum, meaning that twelve or more members of the central committee were in attendance and that at least one representative from each of the county’s Assembly districts was present. Mark Westwood, as an executive committee member dedicated to Robles, would normally have at least sought to assert his authority to block the dissidents’ action. But he was unable to do so because Rita Ramirez Dean was present, and his eligibility to participate in the meeting was voided because his charter as a member of the committee consists of participating only in her absence.

With Ron Cohen presiding over the meeting from that point forward, a vote was taken on whether to ratify Robles’ previous removal of Lori Stalnaker as the committee’s finance director. The vote to ratify Stalnaker’s removal failed by unanimous vote and she was given the opportunity to give her report.

Stalnaker said she has had difficulty completing an audit of the county party’s finances because she has been consistently rebuffed in her efforts over the last several months to obtain minutes of previous meetings so she can reconcile expenditures made out of the committee’s bank account with their authorizations. She referenced several questionable expenditures, including ones made with a lack of receipts, and noted that Robles had apparently authorized via email expenditures for ads with a radio station for which Mark Westwood works.

Cohen asserted that Carol Robb’s appointment to the position of parliamentarian had never been ratified so he made a nomination for Tim Prince to the position. Robb had previously been given the position based on Robles’ action. A motion was made to move Prince into the parliamentarian post, seconded and supported by all but one abstention.

Debbie McAfee moved to remove Chris Robles as a member of the committee, an item that had been added to the agenda after Robles’ departure. A discussion on the merits of Robles’ removal ensued, which included Socorro Cisneros advocating against removing him.

“He said he was not advocating for this Republican,” Cisneros can be heard saying on the recordings of the proceedings. “It was his company. So therefore it wasn’t him. Another argument that Chris used was the body cannot remove a member; that it can only go to the executive board.”

The sentiment of several others, ones diametrically opposed to the utterances of Cisneros, can be heard on the recording.

“Chris worked against someone endorsed by our committee…it is a conflict of interest,” one can be heard saying. “He overextended himself….This isn’t about one side or another, it’s about our committee and whether or not our committee was served, and it wasn’t.”

The members voted to close the debate and the acting secretary read the motion. The motion was moved by Debbie McAfee, seconded and the vote was counted by raising credentials. Chris Robles was removed upon approval by the aye votes of 27 with two abstentions and zero no votes.

Under the bylaws of the central committee, the full committee does not have the authority to remove the central committee chairman. That authority is instilled in the executive committee. Nevertheless, the central committee’s bylaws authorize the removal of any member of the central committee, on a vote of the committee’s general membership, for engaging in specifically proscribed prohibited activities. Among that activity is engaging in the promotion of the candidacy of a political candidate other than a Democrat. In taking the vote to remove Robles’ from the central committee, Robles’ work on behalf of Skropos was cited. The removal of Robles as a committee member by extension relieves him of the committee chairmanship. A vacancy was declared for Robles’ position on the central committee and the office of chair.

The question now is will the California Democratic Party recognize the action by the San Bernardino County Central Committee last night as official.

This morning, Robles told the Sentinel that nothing that occurred after he closed the meeting and took his leave bears the patina of legitimacy. “It was adjourned and no other meeting would be recognized as official,” he said. “What they held was a bogus meeting. Our bylaws are very specific about the removal of a member. It is not something you can do willy-nilly. I am an elected member of this body. It is the same with every organization in the state. You cannot just remove somebody on a whim. It is a serious process and they are not following the process. The executive committee starts the process and then only if the body finds something sufficient. They are trying to bypass that and go straight to the members. The executive committee considered a motion for my removal and found no wrongdoing on my part and found no reason to move forward. That is why you see them making these crazy accusations and holding some type of shadow meeting. When they make their motion, they don’t give the background and full details. They only give information they think will build their case.”

The vote to remove him, Robles said, carries with it no party imprimatur. “The official meeting was held and adjourned for the safety of all of the members when a small group became unruly,” he said. “I assume they are going to try to legitimize this second meeting by stating there was a quorum. But when a meeting is adjourned, there is no continuation. Despite the motion to remove me and the vote, it is not valid. There is more required than those people having a meeting and I am somehow booted out.”

The Sentinel has learned that Ron Cohen, who is among the prime movers within the central committee militating for the removal of Robles and one of only two members of the executive committee in favor of removing Robles as chairman, is scheduled to have a meeting with California Democratic Party Chairman Eric Bauman tomorrow.

Ultimately it is the California State Democratic Party’s rules committee which will make the call as to the legitimacy of the meeting after Robles departed.

County Wants Devereaux Lite In Next CAO

The board of supervisors’ love/hate relationship with Greg Devereaux is shaping in a multitude of ways the pending selection of his ultimate successor.

For over seven years, Devereaux, the one-time city manager of Fontana and the former city manager of Ontario, was the chief executive officer of San Bernardino County. He has only recently departed and remains as a consultant to the county on management issues.

The title and position of chief executive officer was created for Devereaux. Previously, the county’s highest ranking staff member was the county administrative officer, CAO for short, which was distinct from the title of county CEO. Devereaux came to the county in January 2010, in the immediate aftermath of the ouster of Mark Uffer as CAO in December 2009. That had occurred on 3-2 vote, with then board members Gary Ovitt, Brad Mitzelfelt and Neil Derry prevailing against then-board member Paul Biane and Josie Gonzales, the only board member from that era who is yet in place.

Devereaux was respected for his accomplishments in Fontana and Ontario. In Fontana, after a decade-and-a-half of the depredations that city had suffered during the tenure of city manager Jack Ratelle in which sales tax and property tax springbacks to developers had nearly bankrupted the city treasury, the reformist team of city manager John O’Sullivan and reformist finance manager Jim Grissom had made an effort to stabilize the situation and stemmed the giveaways to the political cronies of the city council and the mayor. But more than a decade-and-a-half of deals given to development interests had resulted in commitments that hamstrung the city financially, indeed unto the point of City Hall being crippled altogether. For example, to allow the Ten Ninety Corporation to proceed with its development of the 9,100-unit Southridge Project in the early 1980s, the city agreed to use its redevelopment agency to underwrite the full cost of infrastructure there – a $120 million price tag in 2002 dollars. This entailed $55 million in loans from the glaziers union and $65 million in bond financing in the form of “certificates of participation” not approved in a vote of Fontana citizens but rather a vote of the city council. To service this indebtedness, the city of Fontana was committed for 30 years – until 2013 – to make $3.12 million in bond payments every quarter, that is $1.04 million per month or $12.48 million per year. This deal and others like it made O’Sullivan’s task extremely difficult and in three years on the job he encountered a depth of challenges most city managers do not see in a decade. He was succeeded by Russ Carlsen as city manager, who endeavored to come to terms with the city’s overwhelming financial issues. The torch was passed from Carlsen to Jay Corey. By that time, Devereaux had been hired to serve as Fontana’s redevelopment and housing manager. Devereaux’s brilliance was in evidence at once as he grappled, exhibiting command and confidence, with the seeming intractable financial problems that had put Fontana at the bottom of a pit. When Corey left in 1993, Devereaux was elevated to city manager. In four years he not only succeeded in lifting Fontana out of the abyss, but succeeded in putting that city on firm financial footing that would persist for two decades – to the present – and which looks to remain into the foreseeable future. Under the guidance of Devereaux’s successor, Ken Hunt, Fontana moved on to become what is today – at 212,000 – San Bernardino County’s second largest city population-wise, with the third-largest municipal budget of the county’s 24 cities and the fifth most dynamic economic engine countywide. Hunt at this point is the longest continuously serving and highest paid city manager in the county and is considered to be a model for his peers. Yet it is widely recognized among his colleagues in municipal management and acknowledged by Hunt himself that his career success is largely a function of the dual factors of the advantage he possesses of having succeeded Devereaux and his own good sense of having executed on the formula that Devereaux handed off to him.

Having witnessed the dramatic turnaround in Fontana, the Ontario City Council set about luring Devereaux to Ontario in 1997, where for the next dozen years he ran that city, likewise transforming it through a variety of strategies which had for the most part not been previously utilized.

Incidental to his arrival in Ontario was the advent of the Ontario Mills shopping mall and expansions to Ontario International Airport, which were guided by the city of Los Angeles and the corporation utilized by the Los Angeles Department of Airports to run the airports Los Angeles then owned, including Los Angeles International Airport and Ontario Airport. Those resulted in substantial increases in the city of Ontario’s treasury. Far less apparent, however, were the subtle and more obscure methods that Devereaux used to boost Ontario financially, not the least of which was promoting Ontario as a point of sale for a host of corporations doing business throughout California. Through an effective but unpublicized campaign to have those corporations locate their corporate headquarters in Ontario, Devereaux was able to have the city capture sales tax revenue on the business those entities conducted throughout the state. By keeping this “point of sale” strategy quiet, Devereaux prevented other cities from catching on to the gold mine Ontario was tapping into, thereby reducing the competition the city would have had from other municipalities likewise seeking to exploit the point of sale phenomenon. By 2009, a dozen years after Devereaux had taken the helm in Ontario, the city had a total budget approaching $670 million dollars, meaning the city had more than two-thirds of a billion dollars running through all of its funds annually, such that its financial numbers were more than double that of the next most financially dynamic city is San Bernardino County.

After Uffer was sent packing in November 2009, the county made a show of carrying out a recruitment drive throughout California to replace him, which attracted 277 applications. And while 16 of those applicants were given a second look, in actuality the real action taking place was an attempt spearheaded by county supervisor Gary Ovitt to poach Devereaux from Ontario. Ovitt had been on the Ontario City Council and was mayor during the first six-and-a-half years of Devereaux’s tenure as city manager. So impressed were county officials that Devereaux was able to essentially write his own ticket. In an intense negotiation session that involved Devereaux insisting upon being given the title of chief executive officer as opposed to county administrative office, a degree of autonomy with regard to overseeing, hiring and firing county department heads that went beyond the authority of any previous county administrative officer, a salary and benefit package unparalleled in county history and a so-called superbonus, Devereaux consented to leave Ontario and become the county’s top staff member. The superbonus consisted of a provision written into his employment contract that he could not be removed as chief executive officer on anything less than four votes of the board of supervisors. Thus, the bare 3-2 majority vote that had knelled Uffer’s exodus would be insufficient to terminate Devereaux. His firing could only come if a cause was cited and a substantial number or percentage – 4 out of 5, or 80 percent of the board – agreed to force him out. He was given a ten year-contract that guaranteed he would remain as chief executive officer for five years and provided him with the option of remaining thereafter – with the board’s consent – as chief executive officer or instead transitioning into the position as “special projects” advisor. He was to be paid $319,909 in base salary as chief executive officer together with benefits that would make his total annual compensation eclipse $400,000. As special projects advisor he was to receive $91,000 per year.

His understanding of how to keep all of the moving parts of a large organization in synchronization with one another was unrivaled regionally. While delegating responsibility to department heads, he would intermittently and in some cases even constantly carry out operational control surveys that impressed upon the county’s workers that they were not only answerable, but in some fashion absolutely answerable, to him.

A significant element of Devereaux’s strength was his mastery of the financial bottom line and his ability to force the department heads below him to constrain themselves to the budget imposed on them.

More than two years prior to his coming into the position of county chief executive officer, the county, region, state and nation had been hit with an economic downturn that persisted for more than five years. Thus, the drawdown in revenue available to the county forced successive rounds of belt tightening. This resulted in sometimes testy relations with county employees and their union advocates. Immediately upon becoming chief executive officer, he had to deal with seeking and extracting the reluctant concession of the unions representing county employees to allow the freezing of salaries and reducing benefits. He carried this off but generated a degree of enmity with elements of the county’s workforce and the unions representing them.

An intrinsic part of Devereaux’s management formula is the assertion of control, indeed supercontrol. Devereaux’s absolute authority was a necessary ingredient in his success, as the margin for error and the window for achievement in the arenas in which he functioned were decidedly narrow. His plans were calculated carefully and with precision. Deviation could throw the formula into disarray. His suggestions thus became orders and his orders were exacting. To ensure compliance he sometimes used ruthless tactics. Given the stakes being played for and Devereaux’s overwhelming string of successes to say nothing of the superbonus that had been conferred upon him that made removing him extremely difficult, his political masters on the board of supervisors – who changed in 2010, changed some more in 2012 and changed in 2014 – were willing to tolerate his dictatorial manner and live with his style of having primacy in dealing with county staff and department heads, in large though not total measure cutting the board off from direct interaction with those department heads and staff.

Two major developments in recent years, however, introduced grit into the emollient that previously allowed for smooth gliding of the function between the board and the CEO.

The first was the ascendancy to the board in 2012 and 2014 of, respectively, Robert Lovingood as First District supervisor and Curt Hagman as Fourth District supervisor. Lovingood, as the owner of an employment agency, and Hagman, as a former member of the California Legislature, are strong and in some cases domineering personalities intent on interaction with those working below them in the county government structure, most particularly the echelons immediately below them at the top or near the top of the organizational chart, i.e., the county’s department heads.

The second development was the 2015 scandal that ensnared the county’s previously untouchable human resources director, Andrew Lamberto, in 2015. In the spring of that year while attending a wedding in Orange County, Lamberto was tripped up in a prostitution sting. He informed Devereaux of his citation on the offense shortly thereafter and Devereaux very privately and quietly disposed of the internal county discipline issues attending it by handling the matter administratively and not informing the board of supervisors of Lamberto’s travail. Later in the summer, however, the matter came to light publicly, and in the glare of publicity questions were asked about Devereaux’s motivation in keeping it quiet, with suggestions coming forth that doing so had provided Devereaux with some level of illegitimate leverage over Lamberto that enhanced his already dictatorial reach. While Lamberto did not survive the scandal and was given a severance from the county, Devereaux did survive, but was wounded in the outcome, creating an atmosphere in which the lines of power involving the board and the CEO subtly shifted. Over the next year-and-a-half, against this backdrop the board, or elements of it, began to move toward taking back from the CEO certain levels of authority which signaled to Devereaux that he would not have the unfettered control of the past.

On January 19 Devereaux announced he was retiring and by June would move into the post of a management consultant with the county for three years thereafter.

The use of the term love/hate is an apt one in describing the relationship between Devereaux and the board. Love is appropriate because of Devereaux’s efficiency and the manner in which he made a very large organization for which they bore some level of responsibility run relatively smoothly and in a way that was complimentary to, or at least potentially complimentary to, their own political careers and ambitions. Love because of his willingness to fall on his sword to protect them, absorb or deflect any criticism vectored their way by outsiders. But hate, or a form of it, was applicable to, because at least a few of the board members hated the way he interfered with their alpha male impulses to themselves be in control – not indirect control but direct control – of the machinery of government they headed.

At the time of the announcement, Lovingood and Hagman veiled in a velvet glove their steel-fisted determination to take grip of county government.

“I was hoping to work with Greg throughout my chairmanship,” said Lovingood, who only recently before had been promoted to the position of board chairman by his colleagues. “Greg’s knowledge and ability to work with the board to address the county’s challenges will be missed. He is well respected in the local government and business communities.”

“Greg’s contacts in Sacramento and Washington and throughout Southern California and his knowledge of government have served the board and the county well,” said Hagman. “Greg played a key role working with me and other local leaders to return Ontario International Airport to local control. As the newest member of the board, I had been looking forward to working with Greg as CEO throughout my time on the board. I am glad he will still be available to us in an advisory role.”

The board appointed Dena Smith to serve in the capacity of interim county chief executive officer. Smith had begun with the county in the human resources division, was later clerk of the board, then the head of the land use services division and subsequently an assistant chief executive officer working with Devereaux, essentially as his right hand woman. Meanwhile the county is conducting a recruitment drive to find Devereaux’s full line replacement.

It was initially disclosed that Smith had applied for the post. During this year’s board hearings for the county’s 2017-18 budget, Smith found herself filling the role Devereaux had the previous seven years, the not insubstantial task of previewing that budget. The gap between her mastery of financial issues and the skill that Devereaux exhibited in that regard was immediately obvious and as the hearings progressed, it became increasingly apparent from some of the testy exchanges that took place that the board was less than enamored with Smith’s performance. Subsequently, the Sentinel is informed, Smith took her name out of the hat for consideration for county chief executive officer/county administrative officer.

The Sentinel has learned that the balance of sentiment among the board is that the individual hired to replace Devereaux as the county’s head of operations should not be given the full range of autonomy granted to Devereaux. While the terms under which the next top county manager will be hired and will function have yet to be determined and established and will no doubt be influenced by that successful candidate’s raw talent, experience, determination and charisma, the majority of the board is leaning toward returning toward the model of the county administrative officer, which served San Bernardino County for 61 years.

Under that model, most of the county’s chief administrators were relatively long-lived in the position. The first individual to hold the post after it was created in 1948 was Tony Zenz, who stayed in place until 1958. His successor was Robert Covington, who served a record 17 years as county administrative officer, from 1959 to 1976. Earl Goodwin followed him, remaining for a relatively short four years, from 1976 to 1980. Robert Rigney stayed as county administrative officer from 1980 until 1986 and would very likely have served far longer but for the health challenges that resulted in his leaving and his death the following year. Harry Mays succeeded Rigney, outlasting his predecessor’s six year tenure by two years, staying as the county’s top dog from 1986 until 1994. Mays and his successor, James Hlawek, who remained from 1994 to 1998, are credited, or blamed, for the succession of brief tenures of the CAOs who followed, an outgrowth of the disarray that ensued from Mays’ and Hlawek’s 1998 indictments and subsequent convictions on graft, bribery and political corruption charges. Hlawek’s successor, Carol Shearer, lasted a single year, from 1998 to 1999; William Randolph succeeded her, lasting from 1999 to 2001; John Michaels stopped the gap between 2001 and 2003 and Wally Hill succeeded him, remaining in place one year, from 2003 to 2004. Hill was succeeded by Uffer, whose exodus in 2009 was followed by Devereaux’s ascendancy.

The county board of supervisors are looking to establish the level of stability and perhaps even longevity exemplified by Zenz, Covington, Rigney and Devereaux, while hoping to strike a balance between authority, efficiency functionality and oversight.

Hagman told the Sentinel this week, “We are looking at people who are willing to apply, preliminarily at this point and will become far more focused as we move to the stages where those less qualified are eliminated from consideration. There were those who applied from within the county and outside the county. This will be a fair, methodical process to find the perfect match for the citizens of San Bernardino County and the board.”

Asked if the next county staff leader will be a CEO on the order of Devereaux with a superbonus, Hagman said, “I really don’t see that as the normal trend in government. I am leaning toward the CAO model, but we have yet to see what the rest of my board colleagues think about that. From my point of view, if you lose the confidence of a majority of the board, you should move on.”

With regard to Devereaux’s tendency to insert himself between the board and county staff, Hagman said of the supervisors generally, “We each have our own staffs and district’s to manage. The CEO managed the county in its entirety. Where Greg had issues with some people, I was able to work with him. In our case, you had two strong personalities, obviously, but the CAO has to be able to deal with 20,000 plus employees and all five elected officials, all of who have their own points of view and drive.”

Hagman said that in shifting to a new county staff head and his or her license to run county operations versus the near absolute authority given to Devereaux, “It is hard to say what will be different. It will be someone who has the confidence and trust of the full board. The type of person we are looking for requires someone with what I would not call your typical lifestyle. A CAO has to be ready to receive a call at 5:30 in the morning from a board member or at 11 p.m. on a Sunday night and be responsive, as Greg was sometimes called upon to do by me. They are expected to be available 24/7 and be at their best if they’re called upon. That has to be part of their job and part of their mission in life. It is a different job from most, and some people don’t want that life.” – Mark Gutglueck

Potential Precedent-Setting Challenge Of Annexation Authority Heard

By Ruth Musser-Lopez and Mark Gutglueck

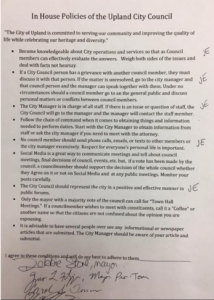

The battle to unwind the recently concluded annexation of both Upland’ and San Antonio Heights into a county fire protection service area was fully joined this morning when the attorney for the San Antonio Heights residents opposing the annexation and the lawyers for the three county entities seeking to perpetuate it had it out before Judge David Cohn. The matter was not fully resolved this morning and lawyers for the San Antonio Heights Association, the county and its Local Agency Formation Commission and the City of Upland will return to Judge Cohn’s courtroom for a status conference on the litigation on September 19, 2017.

Early in the hearing, Judge David Cohn said his reading of the Sunset Beach v. Orange County LAFCO case led him to conclude it is unlikely that the San Antonio Heights Association will prevail on the merits in the case or that he would be issuing the requested injunction. But as the arguments intensified during the two-hour hearing, Cohn appeared to be moving toward some of the assertions that the plaintiff’s attorney, Cory Briggs, was making, and the packed courtroom filled with Upland and San Antonio Heights residents overflowing into the jury box were observably heartened when the judge concluded the hearing by saying he would take the injunction under consideration and enter his decision regarding it in writing. That decision may come as early as next week.

The recently processed annexation of both Upland and San Antonio Heights into the county fire district and the West Valley Service Zone is controversial due to the concomitant annexation of both Upland and San Antonio Heights into the Helendale area “Fire Protection” service “zone,”known as “FP-5,” which is the subject of the contest and prompted the complaint.

After public officials in the cities of San Bernardino, Needles and Twentynine Palms closed out their municipal or community-based fire departments and “annexed their territory” into the FP-5 Service Zone, imposing a flat taxes in those communities ranging from $130 to $150 per year on every parcel within them, the City of Upland took a leaf from those cities’ playbooks and initiated a similar move last fall.

In March, the San Bernardino County Local Agency Formation Commission followed the recommendation of its executive director, Kathleen Rollings-McDonald, to annex Upland to the neighboring and contiguous West Valley Service Area that includes San Antonio Heights. Pundits say that the purpose of this extra move is a strategy, employed by Rollings-McDonald, to comply with the law that requires a territory to be contiguous or adjacent to the district that it is being annexed into at the the time of the annexation. That annexation into the fire district is not the legal issue at contest in the complaint.

At issue is a maneuver by LAFCO to “annex” both San Antonio Heights and Upland into a discontiguous fire service zone of the county fire district, FP-5. The legally defined “zone” was originally formed by a vote of residents in the unincorporated Helendale region of the desert more than a decade ago. Helendale is 48 miles as the crow flies from Upland and 65 miles driving distance from Upland.

The controversial “annexation” of Upland and San Antonio Heights into FP-5 entailed the imposition of a $148.68 annual assessment with inflation adjustments into perpetuity. The county and city agreed to the option of tacking on the FP-5 service zone tax as part of the agreement to defray the cost of the county fire department providing that service. Plaintiffs however, claim state code prohibits annexation of a territory or municipality into a zone, with Briggs characterizing the maneuver as a “Frankenstein Monster Tax” cobbled together to get around the tax code and California Constitution requiring 2/3 majority on a ballot vote before a special tax can be applied.

Further, the plaintiffs argue that the San Bernardino County Local Agency Formation Commission’s scheduled “protest vote” used legally in the case of valid annexations like annexing territory into a city or a district may not be applied to extend a special zone tax that those to be taxed did not vote on, and that annexation of a larger populated city into a distant tiny service zone is strictly prohibited in the state code.

The protest vote that LAFCO conducted, however, consisted of the San Bernardino County Local Agency Formation Commission’s invitation of property owners and voters within each of the jurisdictions to lodge letters of protest against the mixed bag of annexations all bundled up in one package. Each protest letter received was to be counted as a single vote against all varieties of annexations proposed. Any resident or voter not lodging a letter of protest was presumed to have voted to accept the annexation. If 25 percent of the city’s and San Antonio Heights’ voters or landowners lodged protests, than a straightforward election with regard to the formation of the assessment district was to be held. If a majority protested, than the assessment would have been denied outright. As typical of such “protest votes,” nothing approaching sufficient opposition appeared to be manifesting in Upland or in San Antonio Heights to achieve the 25 percent protest threshold.

In response, the San Antonio Heights Homeowners Association retained attorney Cory Briggs to file suit against the city, the county and the Local Formation Commission in an effort to block the annexation. Briggs filed the suit before the July 12 deadline for the reception of protests of the annexation, pairing with it a petition for a temporary restraining order (TRO) to prevent the implementation of the shuttering of the Upland Fire Department and the imposition of the special tax while the lawsuit was being litigated. At the July 10 TRO hearing, Judge David Cohn denied the request, saying it was premature since the outcome of the protest count was unknown and it was possible that there could be enough objections to prevent the annexation from occurring. He set the matter for a later date, July 28, at which time the outcome of the election would be known but prior to the tax being applied to the parcels by the county assessor’s office and bills going out to the property owners.

On July 12, it was manifest that the protest effort had fallen short and on July 22, a week prior to the scheduled hearing the county and the city began implementing the changeover from the City of Upland’s fire department to the county fire district, including changing the logos on city fire trucks, which passed into the custody of the county, along with the city’s four fire stations.

The proceedings today were to hear arguments for or against a preliminary injunction until the matter can be tried. Briggs and attorney Anthony Kim, were in court to ask that the preliminary junction be granted to enjoin the county from applying the special FP-5 Service zone on the property tax bills of Upland and San Antonio Heights on the grounds that the annexation into FP-5 is illegal and is being engaged in by the defendants as a means to avoid the state constitution-guaranteed right to vote on any new special tax.

To counter Briggs and Kim, the Local Agency Formation Commission, the City of Upland and the County of San Bernardino and its separate agency, the Fire District were represented by attorneys Donald Wagner, Ginetta L. Giovinco, and Laura L. Crane, respectively. The foundation of the defense’s argument is one that was argued by Crane at the hearing that a ballot vote and a protest vote are “not coexistent.” She said the agencies “don’t have to satisfy the right to annex” and that “there is a right to vote if there is sufficient protest against the annexation.”

However Briggs and Kim argued that while it is true that the agency has a right to annex, that the taxing aspect of this annexation is illegal. They maintain that the agency cannot legally annex into a zone. The term “service zone” applies to a special tax area of a “district” or “special district,” all terms which are legally defined in the government code. The linchpin of the plaintiff’s case is that while annexations of any territory, including San Antonio Heights and Upland into a district, special district or city are legal, an annexation of a territory into a service zone such as FP-5 of a district or special district, is illegal. Unlike a city, a district or special district into which a municipality can be annexed into, “service zones,” Brigg and Kim assert, are expressly excluded from the definition of an agency that can be annexed into, as per Government Code Section 56036(b)(10).

The city, county and the Local Agency Formation Commission, however, are relying upon the authority of a case, Sunset Beach vs. Orange County LAFCO, and assessment district code in asserting that the extension of the FP-5 Service Zone tax upon Upland and San Antonio Heights and its annexation into Fire Protection Zone 5 is permitted because a zone’s service tax may be extended into an annexed area just as an assessment district tax is extended when a territory is annexed into a district or city with an assessment district.

Briggs and Kim distinguished the cases by explaining the difference between an assessment district tax and a special “service” tax applied in a fire protection zone. Council for the plaintiffs stated that an “improvement zone can only be formed for the sole purpose of improvements. This annexation is not for improvements. It is for service” and suggested to Judge Cohn that it was up to the defendants to explain how these new special “service” taxes can be construed as “improvement” assessments.

Improvements are for structures and buildings, Briggs explained. Fire protection services are something else and treated differently under the law.

He said that the Sunset Beach case was about paying assessment district taxes because Sunset Beach was benefiting from those improvements but that the taxes being foisted upon the residents of Upland and San Antonio Heights were new service taxes, under a totally different section of the law than assessment district taxes.

Giovinco asserted that under Government Code Section 57330(t) any territory annexed to a district or city is subject to any taxes, fees or assessments previously levied in that district or city.

Briggs seized upon that opportunity to say that the county fire district does not have a tax assessment, and that it is only the fire zones which are taxed, again citing government code that strictly prohibits territories being annexed into a fire protection zone and that State Constitution under Propositions 218 and 26 prohibit special taxes being applied without a vote of the property owners or voters.”When you do an annexation you can continue the tax that was already there in the affected territory,” Briggs asserted. “We don’t have that here. We have a tax in another territory being exported.” Briggs said. “Special tax information went out on the ballot to the Helendale, Silver Lakes territory.” Briggs read from the ballot that the voters approved a special tax area that shall not be expanded, nor shall there be any increase without vote. “Helendale said we won’t make this area bigger without going through the procedures to make the territory bigger,” Briggs said. “We didn’t ask anyone in Helendale to ask them if they now want this tax expanded elsewhere” he said, “This annexation is illegal.”

“The term zone trips up Mr. Briggs,” said Wagner. “It should not trip up the court.” Wagner admitted he wished the county would have called FP-5 by a different name than “zone.”

“The district includes a county service area,” said Wagner. “This is a ‘semantics game’ here. The fire district organizes itself as zones, clearly annexing into the district then specifying the zones is appropriate and provides protection for the people sitting behind us so they can make sure they get their monies worth organized the way it is.”

In response, Briggs said, “Mr. Wagner says he wishes they didn’t use the word ‘zone.’ What he really means is ‘I wish my clients would have followed the law…’ This is a Frankenstein tax monster that has been cobbled together.”

Briggs asserted that the Local Agency Formation Commission had blurred the distinction between assessments in an improvement district and special taxes in a fire service zone He told the court that in a response to a question from a member of the public with regard to the legitimacy of annexing into a service zone, the Local Agency Formation Commission’s executive director, Kathleen Rollings-McDonald, replied in an email that the annexation was being made to an improvement zone.

“We don’t have an improvement zone, we have a service zone” Briggs said. “They call it a service zone [in the agreement] and there are half a dozen references to service zone [in the agreement] and the only time the term ‘improvement’ appears anywhere talks about capital improvements to replace equipment. Ninety five percent of the transfer is for service. An improvement zone can only be formed for the sole purpose of improvements. This annexation is not for improvements. It is for service. You cannot rely on the one thing that the LAFCO executive officer says to try to make this case lawful.”

After reading to the judge the legislation supporting his assertion, Briggs concluded, “you can do annexation, but only within this law. The law says that improvements districts are formed for improvements and any others are service zones.”

“LAFCO’s executive officer used the word zone in the title of the title of the plan. The plan is about the FP-5 zone tax.” Briggs charged. “They have given you the plans and every time the tax is discussed it is levied for the zone, it is not levied by the district. Not a single document says it the tax is levied by the district. The evidence does not support that the tax is levied by the district. The tax is levied on a zone, a non contiguous zone, many miles away.”

The Sunset Beach case involved a small population of residents living on Sunset Beach, an unincorporated county area in Orange County adjoining and partially surrounded by the City of Huntington Beach. Those citizens objected to being annexed to the city with the requirement that they also pay the preexisting Huntington Beach special assessment district taxes Those Sunset Beach residents maintained they had not voted on the assessments and therefore should not be forced to pay them. After the trial court agreed with the plaintiffs on the grounds that Proposition 218 protected them against taxes that they had not voted on, Orange County LAFCO appealed to an appellate court, which ruled that the Sunset Beach residents had to accept the assessments once they were a part of the city.

In the Sunset Beach case, Briggs said, the appellate court held that the Proposition 218 protection does not apply to improvement assessments already in place. “But,” said Briggs, “the Sunset Beach case did not address the issue of the even more comprehensive Proposition 26 protection against any new taxes not approved by a vote.” He said that Proposition 26, which was passed in 2010, the same year that the Sunset Beach case was ruled upon and was not yet in effect, had not been considered in the Sunset Beach decision. Therefore, Brigg said, it will be up to Judge Cohn with regard to how Proposition 26 applies in this case.

“Proposition 26 falls to your Honor,” said Briggs. Sunset Beach dealt with non-constitutional issues, Briggs said, reminding the court that in a conflict between Local Agency Formation Commission policy and the California Constitution, the Constitution prevails. “There is strong authority for issuing an injunction,” Brigg said. “The action is void because the agency is not following a coarse prescribed by law. They can’t do an improvement tax, they can’t do a zone tax. The court in Sunset Beach was not concerned about law change concerning new special taxes. The logic of that case said Proposition 218 does not apply because the statutory scheme provides all of the protections But Sunset Beach did not look at Proposition 26,” Briggs said. “Proposition 26 closes loopholes like this one, so even if there is any doubt regarding Proposition 218 not applying to an annexation, Proposition 26 comes along and says this applies to any new tax unless it is one of the exceptions. The defense doesn’t waste any paper on this because nothing in this case fits into an exception under Proposition 26. Sunset Beach is not the authority for a proposition not considered. We don’t know why Proposition 26 was not mentioned in that case, but we put Proposition 26 right up front in our Constitutional argument in this case. The defense never even argued that Proposition 26 was not to close loopholes, any fee, any extension, any charge. If you want to talk about raw language…the Constitutionality issue takes precedence over everything else.”

Briggs and Kim have asserted that the circumstance involving Upland and San Antonio Heights is significantly different from that in Sunset Beach. Sunset Beach was an unincorporated island type area surrounded by, adjacent and contiguous with Huntington Beach. In the case of Upland, it is not an unincorporated county area but an existing municipality and is nowhere near Helendale and in no way adjacent or contiguous.

As to Briggs’ assertion that having a smaller district in an unincorporated area of the county annexing a larger incorporated or municipal area constituted “the tail wagging the dog,” Giovinco dismissed that assertion as an emotional rather than a factual reading. “There is no authority that supports that position,” Giovinco said, asserting that existing law and legislation does not rule out a smaller area welcoming a larger one into its jurisdiction, even if they are not contiguous. Briggs, she said, was engaging in his own wishful interpretation of a law that does not yet exist. “He is arguing [with regard to something] that the legislature needs to [clarify or set in stone].”

But at the hearing Briggs pressed on stating that Sunset Beach involved a specific type of annexation referred to as “island annexation.”

Briggs further maintained that Government Code Section 56119 requires that “any territory annexed to a district shall be contiguous to the district…” Government Code Section 56031(a) defines “contiguous” as “territory adjacent to territory within the local agency.”

According to the suit,“Neither the city nor San Antonio Heights is contiguous to the unincorporated community of Helendale, where the Valley Service Zone and Service Zone FP-5 originated.” Besides, Briggs argued, the FP-5 Zone voters specifically voted against “expansion” of their zone.

Briggs said one of the problems with the agencies’ interpretation of the law is that they have confused the meaning of the term “extend” when they say “a zone’s service tax may be extended into an annexed area.” The legislators defined and the courts recognize that the word is “temporal” meaning time or through time not geographically extended, Briggs asserted. “Extend means the duration, the effective date, nothing more,” Briggs said. “Extending to a geographic location is not the same use of the word,” he propounded.

Judge Cohn asked Briggs “why do you believe you will prevail?”

Briggs said he could summarized his argument in three minutes. In sum he said that first it is illegal to annex a territory into a service zone, and second, since a “service zone” falls under a different definition and code than an “assessment district” that unlike an assessment district, LAFCO can’t just export or extend the hand of a tiny service zone in Helendale to reach over for revenue for services in a distant municipality. This is a new source of revenue. Under Prop 26, if its new revenue and is not one of those exceptions then the agency cannot tax without a 2/3 majority vote.

Briggs concluded by saying that the City of Upland’s inability to budget does not allow its officials to conspire with the Local Agency Formation Commission. “It does not give the right to conspire to put a cockamamie square peg into a round hole,” he said. “FP-5 is not an improvement zone by their own admission. FP-5 is excluded by definition from annexing.”

The defendants argued that an injunction was not needed because taxpayers would be refunded their money if the plaintiffs prevailed.

A consensus appeared to form between Briggs, Cohn, Wagner and GioVinco that the San Antonio Heights plaintiffs might best challenge the annexation through a specialized legal challenge known as a reverse validation. Briggs said he was preparing to lodge that challenge next week, but even so that process could take years and in the meantime, his clients would suffer.

Weighing the harm of the application of the taxes against enjoining the county from processing the taxes, early in this morning’s hearing, Judge Cohn indicated his tentative ruling was to deny the motion for a preliminary injunction. Briggs countered that the county would initiate the collecting of taxes and that plaintiffs would take the case up on appeal and upon prevailing the assessments would need to be returned. He said that it would take several years, but there was only a one-year window for residents to make a claim against the county for the return of the money. Moreover he said, each taxpayer will need to make a separate filing to have the money returned, saying the court would be clogged with “50,000 lawsuits and 50,000 claims” for a refund.

The citizens of Upland and San Antonio Heights, Briggs said, “have the right to vote on whether this tax will be applied to them.”

“They [the city, the Local Agency Formation Commission and the county] haven’t proceeded in the manner the law requires. Respecting the public’s right to vote might might be painful but they didn’t follow the rules,” Briggs said. “That’s on them, not on the voting public, not on the taxpaying public.”

Wagner, however, said the right to vote is not unlimited.

“Your honor knows,” Wagner said, “the right to vote is defined. We don’t have the right to vote for the [U.S] Attorney General. The Consititution gives us the right to vote for president. The right to vote can be circumscribed by the government. The right to vote is not absolute in some circumstances. The right to vote doesnt apply to the annexation.”

The residents of San Antonio Heights are demanding more than that to which they are entitled, Wagner suggested.

“What we have are people who haven’t paid for fire service and who have been freeloaders for so long they would like to continue to have the the right to not pay for their fire service.”

This provoked a groan from many of the more than 50 Upland and San Antonio Heights residents attending the hearing. This was followed by a response from Briggs.

“I don’t appreciate calling them freeloaders,” said Briggs. They have been paying ad valorem [property] taxes for years.

Giovinco asserted that under Government Code Section 57330 any territory annexed to district or city is subject to any taxes, fees or assessments previously levied in that district or city.

Cohn said he was taking all of the arguments under advisement and would issue a written order in the days to come. He set September 19 as the date for another hearing.

Four Contestants Have Already Declared For 2018’s San Bernardino Mayoral Election

Councilman John Valdivia’s challenge of incumbent San Bernardino Mayor Cary Davis has triggered a spate of candidates seeking the top political spot at the municipal level in the county seat.

Mike Gallo and Daniel Malmuth have now declared their candidacies, meaning it will be at least a four-way race when the city holds its first regularly scheduled mayoral race in an even-numbered year next spring.

City voters’ adoption of a new city charter last year, revamping in significant measure the municipal operating blueprint that was in place in San Bernardino since 1905, has changed more than just the years in which elections will be held. In fact, the charter has lessened to some degree the power the mayor once had. Whereas previously, the mayor did not have a vote except in those circumstances when there was a tie, the old charter gave him veto power when the vote for passage was 4 to 3 or 3 to 2. The mayor presided over the meetings of the city council and had control over the issues to be discussed as well as the ebb and flow of that discussion. Under the previous charter, the mayor had power that went beyond mere political control, as he was vouchsafed what bordered on a co-regency with the city manager in terms of the day-to-day management or direction of operations at City Hall, including decision-making power with regard to personnel, in terms of hirings and firings. While there was talk of giving the mayor voting power when the form of the new charter was under discussion beginning two years ago, that was to have come with the reduction of the number of council wards from seven to six. The number of wards remained unchanged in the new charter, and thus the mayor still no longer has voting power unless an issue voted upon by the council has ended in a tie. The mayor retains veto power, which essentially gives him two votes if the council splits 4 to 3 or 3 to 2 on any of the issues before it. But the charter removed the mayor’s non-political primacy at City Hall, so he or she, in this case Davis, no longer has the reach to run the city in conjunction with the city manager. Nevertheless, the mayoralty in what remains as yet the county’s oldest and most populous city is yet considered an honored prize.

For that reason, Gallo, the president and chief executive officer of Kelly Space & Technology and a San Bernardino City Unified School District board member, has thrown his hat in the ring.

Gallo refers to himself as a consensus builder who has sought to have collective meetings of community business leaders, social leaders and elected officials to discuss issues and forge that consensus and set goals.

Gallo and his supporter tout the school district upping its graduation rate from 67.5 percent to 86.2 percent.

Gallo, an appointee to the California Workforce Development Board, including its executive board and the Career Pathways and Education Committee of which he was chairman, became enamored of San Bernardino when he was stationed as at Norton Air Force Base in the early 1980s. When he left the Air Force he went to work for TRW Ballistic Missiles Division. In 1993, he co-founded Kelly Space & Technology, which conducts aerospace research, development and testing at the now converted Norton Air Force Base, now called San Bernardino International Airport.

Malmuth, who worked in the movie industry and was a member of the San Bernardino Historic Preservation Commission and Art Commission, chose the headquarters for the San Bernardino Historical and Pioneer Society to announce his candidacy.

Career-wise, Malmuth began as production assistant at Columbia Pictures before moving on to direct some movies in the capacity of associate director before being entrused to serve as a production executive on movies with budgets well into the eight figures.

Malmuth sees San Bernardino as something like the Anaheim of the 21st Century, with a major movie studio choosing it to become host to a world class theme park called Joyland. He says the park could begin on the 48-acre footprint of the now delapidating Carousel Mall. And San Bernardino could take advantage of its location at the foot of the mountains and its climate to make itself into a new Hollywood. He said he would appoint a deputy mayor to oversee film making in the city. That deputy mayor would be accompanied by five others under Malmuth’s vision for municipal governance, with these mayoral delegates dedicated to preservation, openness and transparency, economic development and artistic development. He said he would seek to relocate City Hall into the Arrowhead Springs Hotel.

Davis, who in the 2013 election finished second among a slew of candidates to make his way into a run-off election against Wendy McCammack in 2014 which he then won, saw his four year term extended by a year as part of the charter change. The city will hold its next municipal election in synchronization with the gubernatorial primary in June 2018. If a runoff is required because no single candidate gets a majority in the voting, that recontest will be held in November 2018.

Chino Chooses Rodriguez To Fill Gap Left By Duncan Departure

Dr. Paul Rodriguez, the third cousin of a former councilman, has been chosen to replace Glenn Duncan on the Chino City Council.

The city council voted 3-1 during a special session prior to its July 18 meeting, with mayor Eunice Ulloa dissenting, to appoint Rodriquez, an educator who had previously vied for the council. He will represent District 1 on the city’s newly created council ward map. His term will expire after the November 2018 election.

The vote was held at a special meeting that started directly before the regular council meeting on July 18.

Rodriguez was not the first candidate nominated. Councilman Gary George moved initially to consider planning commissioner Harvey Luth. Luth was supported by Ulloa, but failed to garner the backing of councilmen Tom Haughey and Earl Elrod. Elrod then nominated Rodriguez, which was seconded by Haughey. When George supported Rodriguez in the vote, the matter was closed.

Rodriguez did not join the council for its scheduled agenda at the regular meeting that night but was sworn in at the end of the council’s final action on the regular agenda items. He was in place to hear the council reports that typically close the council’s public session and he then accompanied his colleagues into a closed session, during which no reportable action was taken.

Ezekiel Ortiz, Rodriguez’s grandmother’s first cousin, was a member of the city council in the 1940s.

In One Day, Over $300M In Jail Abuse Cases Settle For A Penny On The Dollar

After more than three years of litigation, San Bernardino County in the last six weeks settled for a total of $2,745,000 seven separate lawsuits growing out of the Spring 2014 revelations of severe abuse of inmates at the West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga. A total of 32 inmates or former inmates were represented in those suits, which had sought far in excess of the eventual settlement amount.

In one case involving six inmates originally represented by attorneys Stan Hodge, Jim Terrell and Sharon Bruner, it was alleged the inmates had been subjected to such horrific treatment at the hands of San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies that they should collectively recover a total of $180-million, $15 million in compensatory damages for physical, mental and emotional injury to each plaintiff along with $15 million for exemplary and punitive damages for each plaintiff, in addition to attorney fees. That suit on behalf of John Hanson, Lamar Graves, Brandon Schilling, Christopher J. Sly, Eddie Caldero and Michael Mesa, all of whom were housed at West Valley between January 1, 2013 and the end of March 2014, was filed in U.S. Federal Court in May 2014. Ultimately, on July 11 of this year, the county settled for $2.5 million the Hanson, Graves, Schilling, Sly, Caldero and Mesa lawsuit and six other lawsuits on behalf of 26 other plaintiffs represented by Hodge, Terrell and Bruner. Dale Galipo, whose reputation proceeds him as an aggressive litigator on wrongful death, brutality and excessive force cases, joined with Hodge, Terrell and Bruner as co-counsel three months ago, a signal the legal team was ready to go to trial. There was nevertheless an obvious and substantial discrepancy between the more than $300 million sought in the various lawsuits and the total $2.5 million settlement, a settlement of less than a penny on the dollar.

Two weeks before Hodge, Terrell, Bruner and Galipo closed out the seven cases, on June 27, the county settled a lawsuit brought against it by former inmate plaintiff Eric Smith for $175,000. In January 2015 Smith filed a lawsuit in which he alleged that as an inmate at West Valley who was given trustee status as a meal server within the jail he he was subjected to repeated jolts from Tasers on multiple occasions as well as sleep deprivation and calculated psychological torture.

A week before that, on June 21, the county settled with plaintiff Armando Marquez on his claims of physical and psychological abuse for $70,000.

A lawsuit filed by attorney Robert McKernan on behalf of four inmates, Keith Courtney, Daniel Vargas, Mario Villa and Anthony Gomez, is in the settlement negotiation phase and is unlikely to go to trial. That is not the case of a lawsuit brought in August 2014 by attorney Scott Eadie on behalf of inmate Cesar Vasquez, who is at this point scheduled to go to trial against the county in July 2018.

According to the lawsuit filed on behalf of Hanson, Graves, Schilling, Sly, Caldero and Mesa, “During the plaintiffs’ incarceration the plaintiffs were subjected by defendants to beatings, torture including but not limited to extending the handcuffed arms behind the plaintiffs causing extraordinary pain to plaintiffs’ bodies, electric shock, including electric shock to their genitalia, sleep deprivation, had shotguns placed to their heads, and sodomy. All these actions were taken without any legitimate purpose. The defendants thereby deprived the plaintiffs the right to be free from punishment without due process of law pursuant to the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.”

The allegations of sodomy pertained to aggressive body cavity searches carried out by guards at the facility.

The suit alleges that “As a direct and proximate result of the conduct of the defendants the plaintiffs have suffered extreme physical and emotional injury. The conduct of the defendants was willful, malicious and designed to inflict pain.”

The suit maintains the defendants’ conduct “was under the color of state law. Each of the individual defendants are being sued in their individual capacity as well as their official capacity.”

Language in the suit suggests that the mistreatment of the prisoners was documented by medical treatment subsequently provided to them. “Those plaintiffs who were permitted by the defendants to obtain medical treatment had to receive such treatment due to the conduct of the defendants,” the lawsuit states.

Among those named as defendants in the suits were San Bernardino County Sheriff John McMahon, West Valley Detention Center commander captain Jeff Rose, seven deputies initially identified by the last names of Teychea, Oakley, Copas, Escomilla, Morris, Snell, and Strifler, as well as two civilian jailers with the last names of Stockman and Neil, along with the county of San Bernardino and up to ten yet-to-be-identified members of the department. Subsequently, the seven deputies were identified as Brock Teyechea, Nicholas Oakley, Russell Kopasz, Robert Escamilla Robert Morris, Eric Smale and Daniel Stryffeler. An eighth deputy, Andrew Cruz, was identified as one of the unnamed defendants. Brandon Stockman was identified as one of the unsworn civilian jailers.

In late February 2014, the FBI was provided with a report of widespread abuse of inmates at the jail. In early April 2014, during the early stages of the federal inquiry, three deputies were “walked off” the grounds of the facility by federal agents. Those three were identified as Teyechea, Oakley and Cruz, all of whom had not yet been with the department a full year and were thus considered to be within their probationary term where they could be fired at will. They were terminated on the strength of the FBI’s initial findings. Stryffeler. reportedly voluntarily resigned

In October 2014, Escamilla, Kopasz, Morris and Smale were placed on paid administrative leave and subsequently let go.

The suit said the knowledge of the abuse went right to the top of the department. “The defendant John McMahon and the defendant Jeff Rose and their subordinate administrators sued herein had knowledge that the abusive conduct by which the plaintiffs were deprived of their civil rights were taking place and were going to take place in the future and failed to take any action to cause the violation of plaintiffs’ rights to be prevented.”

The department maintains that McMahon had no knowledge or understanding of what took place inside the West Valley Detention Center and that he has since assisted the FBI in its investigation. The department claims there has been a surge in inmates assaulting one another as well as violence against jailors in the aftermath of the 2011 prison realignment, which has resulted in inmates who would otherwise be housed in state prison now being incarcerated locally.

Early in the litigative process, the county sought to challenge the validity of the lawsuit by claiming the inmates alleging abuse had filed no grievances. The department has since acknowledged that the inmates were discouraged in many cases from filing grievances against their jailors.

Over the last two years, the department has upped the number of security cameras tracking guards and inmates at West Valley.

A federal grand jury was impaneled in 2015 to consider the allegations of abuse at West Valley. No indictments have yet been returned. Fact finding by the FBI is yet ongoing. -Mark Gutglueck

Forum… Or Against ’em

By Count Friedrich von Olsen

Egad! I find this report of warring factions within the presidential administration pitting Reince Priebus against Anthony Scaramucci so disheartening. Does no one adhere to the 11th Commandment anymore? We Republicans should not be fighting Republicans, but the true enemy – the Democrats. I would not presume to offer President Trump advice, but I will say how I keep the peace in my household between two fabulously accomplished personnel serving me. The secret is not only separate quarters, but separate floors. My chauffeur, Anthony, has his bedroom on the ground floor. My butler, Hudson, sleeps in his room on the third floor. I keep the peace by passing my nocturns in blissful somnolence between them, on the second floor…

Randsburg, Atolia & Red Mountain

Red Mountain is a mining district located at an elevation of roughly 3,600 feet in the Mojave Desert along what is now Highway 395, some 23 miles north of Kramer Junction. It was the location of a significant silver mine in a general geographic area that was notable for gold mines. It was originally named Osdick after one if the early miners that worked the area.

Not too far across the San Bernardino County line in Kern County, on April 25, 1895, three miners, Charles A. Burcham, F.M. Mooers and John Singleton discovered gold in the area at a place they designated as Rand Camp. Rand Camp would later become known as the Yellow Aster Mine and the town that grew about it was called Randsburg, the population of which by 1896 had swelled to 1,500. A post office was established there on April 16, 1896. In 1897 the first bank in the area was established in Randsburg. Shortly thereafter a grammar school was in operation. In 1898 the Randsburg Railroad from Kramer Junction was completed on January 5 and later that year the Yellow Aster Mine was augmented with a 30 stamp mill. A church was established and in January 1899 the population had reached 3,500. The Orpheum Theatre was built that year. According to a newspaper report, $3 million in gold was taken out of the Yellow Aster Mine in 1900. The following year a new grammar school was built along with a new 100 stamp mill. In 1903, there was a labor strike at the Yellow Aster Mine.

In 1904, the Santa Barbara Church was built in Randsburg after the previous place of worship burned. In 1905 tungsten was discovered in Atolia, which is roughly 5 miles south of Randsburg on Highway 395. in northwestern San Bernardino Counthy. The town got its name from two mining company officials, Atkins and DeGolia. As Atolio grew, it boasted being host to a dairy, a movie theater, and the Bucket of Blood saloon.

In 1911, the Yellow Aster Mine produce $6 million worth of gold. In 1913 Charles A. Burcham died and in May 1914 John Singleton died, leaving Dr. Rose Burcham as the sole owner of the Yellow Aster Mine.

In 1915 Dave Bowman found a gold nugget in Red Rock Cajon which sold for $1,979 and Al Wiser and Charles Koehn found a sizable nugget at their mine near Red Rock Cajon and Last Chance Canyon Road.

By 1916 there was a tungsten boom in Atolia when the price had increased to $90 per unit. Atolia’s population surged to 2,000.

With America’s 1917 entrance into WWI, which was then called The Great War, the population in the area dropped dramatically. This was exacerbated by a flu epidemic. The town of Randsburg and its outlying gold mining district was dying. But in 1918 silver was found in substantial quantities by some miners prospecting in San Bernardino County in what is now Red Mountain. A boom ensued there, with the Kelly Mine being the most prolific source. A stamp mill, the vestiges of which are yet extant, was built. In 1922, the town, then called Osdick, garnered a post office. The rich lode of silver in Red Mountain attracted miners who were willing to use their success in Red Mountain to stake them to prospecting forays for more valuable gold across the Kern County line.