By clicking on the blue portal below, you can download a PDF of the October 27 edition of the San Bernardino County Sentinel.

Monthly Archives: October 2017

Wonder Valley Chromium & Arsenic H2O Levels 1,000 Times Over Limit

By Mark Gutglueck

The San Bernardino County Fire Department’s reflexive move to protect its firefighters in reaction to the discovery of well water contamination in Wonder Valley is raising the specter of a wider contamination hazard that represents a threat to the well-being of the community’s residents generally.

Indications are, however, that there is no county agency mandated with responsibility to safeguard residents and their drinking water supply in the face of the risk that has been identified.

Wonder Valley is an unincorporated community roughly 10 miles east of the City of Twentynine Palms and approximately 15 miles northeast of the east entrance to Joshua Tree National Park. The town lies south of the Sheep Hole Mountains and Bullion Mountains and north of the Pinto Mountains at an elevation range of 1,200 feet to 1,800 feet near the confluence of the higher-elevation Mojave Desert and the lower-elevation Colorado Desert. Both Amboy Road and State Route 62 run through Wonder Valley and exist as the community’s primary paved roads, with the vast majority of the community’s streets existing as dirt roads or ones that have been oiled and impacted. Wonder Valley boasts a population of some 650; some 3,000 recreational cabins and more permanent living structures built by homesteaders under the Small Tract Act, also known as the “Baby Homestead Act,” between 1938 and the mid-1960s, once dotted the landscape in the 150-square-mile area, though hundreds were demolished and removed as part of a clean-up effort over the last two decades. Most of these remaining structures, sometimes called “jackrabbit homesteads,” are vacant or abandoned. Wonder Valley lies within the county’s Third Supervisorial District, currently overseen by supervisor James Ramos.

Until 2005 the rural community managed on its own, with the augmentation funding due it from the state and county. For more than half of a century it fended for itself with regard to the provision of basic fire protection service, utilizing a paid call firefighting staff working out of its traditional Wonder Valley Fire Station. After the community voted to become a special county fire district tax zone, the volunteer fire department was subsumed by the county fire department a little more than a decade ago. The San Bernardino County Fire Department operated Station 45, located at 80526 Amboy Road, manned with both on-call firefighters and volunteers along with two professional, full-time firefighters, serving under the command of a county fire division commander, in this case Captain Mike Bilheimer, who was formerly a senior officer with the San Bernardino City Fire Department until that entity was annexed into the county fire division in 2015. Earlier this year, there was some concern that the county, as part of its budget for 2017-18, was going to close out the Wonder Valley Fire Station. When the first version of the county budget was released in May, it did not include funding for the Wonder Valley fire station. But county supervisors elected to maintain budgeting for the station after it was demonstrated that the call volume there justified its continuing operation.

In September, an analysis was done on water drawn from the well Station 45 uses. It was discovered that the water was contaminated with arsenic, hexavalent chromium and fluoride at levels approaching or exceeding 1,000 times the threshold deemed safe for human use and consumption. On September 22, the county shut the fire station down, relocating the crew, which at that time included battalion chief Mike Snow, to the Twentynine Palms fire station. The reason given was the threat to the health of the firefighters.

Reliable sources have indicated that testing done on other wells in Wonder Valley showed contamination levels consistent with that in the well used by the fire station for its water supply. The county fire division is said to be looking at how to redress the water contamination issue pertaining to the well utilized by Station 45, including putting a water filtering system into place at the fire station. It has not been established, however, that such a system will reduce the contaminant level sufficiently to render the water safe. At this point, a solution to the problem has eluded the county fire division and the fire station remains closed.

San Bernardino County Fire Department Public Information Officer Tracey Martinez told the Sentinel on Wednesday, “The San Bernardino County Fire Protection District relocated its Wonder Valley Fire Crew to a fire station in Twentynine Palms while the water hazards are being evaluated. This is due to the safety concern for the fire crew. If and when the water concern is mitigated, county fire will re-evaluate the use of Station 45 in Wonder Valley. Until such time, the fire crew will continue responding to calls for service in the Wonder Valley area from Twentynine Palms.”

The Sentinel learned on Wednesday that the situation with regard to water in Wonder Valley had been brought to the attention of a county special districts division manager as well as Jeff Rigney, the director of San Bernardino County Special Districts, which is the closest approximation to a governmental authority for the area, though the special districts division is not responsible for the water supply in Wonder Valley.

Information available to the Sentinel is that the water sample drawn from the well serving Fire Station 45, in addition to being contaminated with hexavalent chromium, fluoride and arsenic, was also contaminated with at least ten other toxic chemicals or elements.

In the face of the swift reaction of county officials in protecting the firefighters at Station 45, some Wonder Valley residents took umbrage in considering that the county made no provisions to protect residents at large, who are using the same water supply. After pointing that reality out, residents asked why the county could not merely disconnect the station’s water piping system from the well, transport one of the several water tanks the county owns to the grounds of Station 45, fill it periodically with imported water and connect it to the firehouse’s piping system, pressurize it and have the firefighters use it. Residents tell the Sentinel that option was kiboshed by Mark Lundquist, one of Third District County Supervisor James Ramos’ field representatives, who said that Ramos and his board colleagues had passed an ordinance last year prohibiting just such importations of water going forward. The same ordinance, Lundquist said, proscribed Wonder Valley residents from constructing their own tanks to similarly ensure the safety of their own water supply. Lundquist did make clear, however, the Sentinel is told, that those who had water tanks which preexisted the ordinance were given license under a “grandfather clause” to store and use imported water.

Lundquist’s reported statements were contradicted by the county’s official spokesperson, David Wert, who told the Sentinel on Wednesday that “there is no county ordinance addressing hauled water, much less anything enacted earlier this year. The county has a long-standing practice of not permitting hauled water as a water source for new residential construction due to the risk of contamination. But that was superseded by a pair of 2016 state laws that prohibit the use of hauled water as a source of water for new single residential construction. People who used hauled water prior to the state laws (and the county’s practice) are grandfathered in.”

Wert went on to say, “The county does not provide water service to Wonder Valley. Actually, there are very few places in the county where the county is responsible for water service. Water is not a service counties or cities are required to provide to their residents. All but a relative few county residents are served by private water companies, independent water districts, or private wells. All properties in Wonder Valley are served by individual wells, and requirements for testing are very limited. It is essentially the responsibility of each well/property owner to monitor and ensure water quality.”

There is no county agency mandated to monitor water quality and ensure its safety on an ongoing basis, county officials said, and both well owners and those consuming the water drawn from those wells are on their own.

Felisa Cardona, the county’s assistant public information officer on Thursday said, “I was able to confirm that [the county’s] environmental health [department] has to inspect and permit newly dug wells but after that it is up to the property owner to have their well tested. At the time of drilling a new well, the San Bernardino County Department of Environmental Health Services does provide property owners with information about testing and/or treating their water, but again it is up to the property owner to have their water tested and/or treated.”

Industry’s Tres Hermanos Sun Power Plan Begets Greater Uncertainty

The inevitable development of Tres Hermanos Ranch remains fraught with uncertainty. That is the case even after the City of Industry, which recently reasserted ownership and control of the 2,450-acre property straddling Chino Hills and Diamond Bar, has declared its intention of converting the bucolic expanse into a 450-megawatt solar power generating field.

Chino Hills and Diamond Bar officials, who have for some time complained that the City of Industry has been far too secretive with regard to how it truly intends to utilize the property, continue to perceive an inexactitude to Industry’s representations that borders on the duplicitous. Meanwhile, City of Industry officials, whose predecessors in 1978 spent $12.1 million to acquire the property and subsequently transferred ownership of it to their redevelopment agency, in August agreed to reacquire the land at a cost of $41.65 million. That reacquisition was necessitated after legislation passed by the California Assembly and Senate in 2011 closed out municipal redevelopment agencies and left the property in limbo. Having now expended $53.75 million to gain control of it, Industry officials feel they have earned the right to put the property to use as they see fit. They claim using it to accommodate thousands of rows of solar panel arrays to generate renewable energy which can then be used to power both heavy, medium and light industrial operations in the City of Industry is a responsible use of the property and one now fully within its rights. They insist the property will simultaneously accommodate a 450 megawatt solar farm and creatively-used open space such as hiking trails and recreational amenities.

Industry officials put themselves into position to take back ownership of the property on August 24, when what is referred to as the oversight board – a Los Angeles County entity representing the various property tax revenue receiving agencies in that area which stood to receive a portion of the proceeds from the sale of the City of Industry’s former redevelopment agency assets, agreed to allow the sale to go forward, despite previous indications that there were other potential buyers willing to pay as much as $101 million for the 2,450 acres.

Residents in Chino Hills and Diamond Bar have grown accustomed to Tres Hermanos’ rolling hillsides, canyon creeks and oak woodlands beside verdant pastures for cattle as a picturesque backdrop for their own community. Many of them have assumed that the ranch, with its proliferating bobcats, mountain lions, skunks and opossum, exists as a wildland preserve. In reality the property has been subject to sale and eventual intensified use and development all along. Many of those residents are now disturbed to learn that it will in coming years be blanketed with solar panels. They are equally appalled at one of the alternatives to those thousands of panels that has been mentioned on and off: residential development.

Both Chino Hills and Diamond Bar officials in August initiated procedural efforts with the California Department of Finance to challenge Industry’s move to purchase the property for use as a solar farm, and on October 20 the City of Chino Hills augmented those challenges with legal action filed in Sacramento Superior Court. A fair sprinkling of residents from both cities are distrustful of that course of action, perceiving, if not entirely accurately, that those challenges, either intentionally or inadvertently, will result in what those residents consider to be the more ominous eventuality of the property being converted to residential subdivisions, with thousands and maybe even tens of thousands of residents being packed and stacked onto the land, and the thousands or even tens of thousands of cars those new residents drive adding to the morning and evening rush hour commuting nightmare current residents are already dealing with.

Chino Hills officials maintain the residential development they envisage on the property will at its maximum be less than one-tenth of the intensity postulated by those reflexively rejecting Chino Hills’ alternative plan for the property’s development.

On its website, the City of Chino Hills has officially stated “Industry has resisted any meaningful dialogue regarding development schemes.” On the same website, Chino Hills officials have claimed that the City of Industry and its officials have engaged in questionable activities and contracts relating to the property. The website references the $41.65 million sale, noting, “The latest appraisal for the property was $100 million, which Industry had agreed to pay. A restrictive covenant was added that would not allow the land to be used for any purpose other than open space, public use, and preservation. The covenant is meaningless however, because state law only allows a city to own property outside [its] boundaries for these types of public purposes anyway. Thus, the oversight board’s reduction of the price by $60 million for the covenant served no purpose. What the restrictions are, and the plan for the solar farm, are very low on specifics. Industry officials act as though they are saving the region from more housing and traffic woes, and providing hiking trails and open space for people to enjoy. Yet the amount of energy they want to generate on the solar farm would seem to require solar panels on nearly the entire 2,450 acres. They’ve spent $10 million dollars in the last year studying the project but they have no design, no footprint, no specifics.”

A subset of Chino Hills residents, nonetheless, is skeptical of Chino Hills City Hall’s show of resistance to the City of Industry plan. They fear that if the City of Industry is thwarted in its effort to develop the solar farm, its officials will retaliate by instead developing the property to accommodate some 10,000 to 15,000 homes or apartment units.

On its website, the City of Chino Hills propounds that worries that stopping the solar power juggernaut will result in the City of Industry transitioning to an even more aggressive residential development scheme on the property are misplaced. The website references Measure U, a voter initiative passed by Chino Hills residents in 1999 which prohibits zone changes increasing density designated in the Chino Hills Specific Plan, the Chino Hills General Plan, the city’s zoning map, or any finalized development agreements without approval by a majority vote of the electorate of the city.

“Some worry that developers will build tens of thousands of homes on Tres Hermanos Ranch,” the Chino Hills website states. “In fact, Diamond Bar’s general plan allows 624 units. Chino Hills’ general plan calls for a maximum of 675 housing units. Measure U prohibits the city from increasing residential units in the city without voter approval. The city’s general plan requires any future development of Tres Hermanos to be master planned. Chino Hills has used a master-plan process to cluster development and protect the maximum amount of open space. For zoning purposes, Chino Hills has slated most development on the mostly-flat parcel of approximately 50 acres located on both sides of Grand Avenue to meet state affordable housing requirements. The general plan includes 103 very high density units, 364 mixed use units, and 15 acres of commercial development allocated to the 50-acre parcel. In addition, there are 208 agriculture ranch units which allow one unit per 5 acres. Limited development has always been included in planning documents for Tres Hermanos: the County of San Bernardino’s Chino Hills Specific Plan (1982) identified the Tres Hermanos Ranch as one of the eight Chino Hills’ villages with a development potential of 358 residential units, 16 acres of commercial within a village core that also included a school and community center or library. The city’s first general plan retained the 358 residential units despite the City of Industry’s request to increase the number of units to 2,600, and included the commercial area and village core area of approximately 50 acres.”

Chino Hills officials, in particular mayor Ray Marquez and city manager Konradt Bartlam, have expressed the belief that what the City of Industry is attempting to do is use the general population’s abhorrence of densely packed residential development to stampede everyone into accepting the solar farm as an alternative. In that way, Bartlam suggested, the City of Industry is hoping to be able to saturate the property with solar arrays.

Former Chino Hills City Councilwoman Rossana Mitchell offered her view that neither City of Industry nor Chino Hills officials are being straightforward. Each side, she suggested, is offering only half of the story and somewhere between half and two-thirds of each side’s narrative is untrue or questionable.

“This discussion is not about maintaining open space,” Mitchell said. “If the City of Chino Hills was truly interested in doing what its residents want done, then they’d change the zoning. They could have done that a long time ago. They could have changed it to traditional agricultural use or open space. They’ve had plenty of time.”

Mitchell said, “I am not in support of a solar farm and I don’t think the residents of Chino Hills are either. What the residents want is no housing and no development, and as much open space as possible. So now there is a battle between Chino Hills and the City of Industry. If it comes down to a legal contest and, for the sake of discussion, Chino Hills prevails, what do we get? High density residential, commercial development and maybe a golf course. The residents don’t want that. So, for the sake of discussion, let’s say it goes the other way and after all that expensive litigation, the City of Industry wins. What do we get? A solar farm. How monstrous is that solar farm going to be? The residents lose that way, too. Where are the details? I haven’t seen them.”

Mitchell said there was some validity to what either side was saying. For example she said, Chino Hills City Hall’s claim that the City of Industry had been less than transparent with regard to its intentions was true.

“The solar farm was pretty much under the radar,” she said. “It snuck up on everyone suddenly.”

But that is not to say that the City of Chino Hills has the purest of motives and intents, she said.

“The City of Chino Hills hasn’t stepped up to the plate either,” she said. “The only thing I’ve heard them say is, ‘We want to build according to our zoning.’ That is what the city manager says. I don’t think Chino Hills residents support what is being pushed by the city [of Chino Hills], which is the city manager’s agenda to build out. What that means is more houses, more cars and more traffic and more aggravation for the residents who live here. No one is speaking on our behalf. I don’t think there is a win in this situation. Honestly, the City of Chino Hills should not be zoning that land as high density residential with a commercial component. How is that any better than solar panels? That is not what the city residents want.”

Moreover, Mitchell said, once even a portion of Tres Hermanos Ranch is converted into homes, “We’ll be heading down a slippery slope. Once we start building houses there, where is it going to stop? It can be rezoned piece by piece, a little bit at a time. How can you jump into a swimming pool and just get a little bit wet? It can’t be done.”

Mitchell conceded that preventing the development of Tres Hermanos Ranch is probably impossible. “Real property rights is a huge issue,” she said. And keeping the property from being developed would result in “losing a lot of revenue,” she said. Still, she said, “What really should happen is that land should just be left as open space. That’s probably a pipe dream.”

Mitchell said the residents were being treated to the spectacle of “Chino Hills officials calling the politicians in the City of Industry bad guys and the City of Industry saying Chino Hills’ leaders are bad guys. This isn’t the good guys against the bad guys. They’re all bad guys. The bottom line is the City of Industry is into this to make money, just like Chino Hills is going to put in there what it wants to make money. They’re both trying to profit.”

Mitchell predicted that the City of Chino Hills will spend a considerable amount of money on lawyers trying to stop the City of Industry from succeeding with its plan and “convince everyone that the City of Industry is lying and that there will be no open space left if the plan to put in the solar plant goes through. If the city [Chino Hills] wins, it will turn around and start building homes. When the residents find out what is really going on, it is going to be bad. It is going to get ugly.”

Mayor Marquez has dismissed Mitchell’s characterizations of Chino Hills city officials’ intent as inaccurate, suggesting that the city’s efforts, which include the procedural challenge of the sale of the land to the City of Industry and the filing of legal action with regard to the solar project, as a sincere attempt to ensure that the City of Industry does not overburden the property. He said that his vision was that a portion of the property could be preserved in something approaching its current state, as “a wildlife corridor with trails all the way from Diamond Bar and across Chino Hills and into Tonner Canyon.” He said a trade-off to effectuate that might be obtained by allowing housing within the city’s current density limits per its zoning restrictions on the northern portion of the ranch on one or both sides of Grand Avenue.

Bartlam told the Sentinel that the City of Chino Hills failing to stand by its current land use specifications, which include the zoning to allow for residential development, could prove disastrous. He said that acceding to the City of Industry’s plan to develop the solar farm as a “public use” quite possibly would mean that Chino Hills and Diamond Bar would surrender their land use authority over the property. “We’re pretty much convinced that the City of Industry can do as they please with respect to future land uses,” Bartlam said. “That is what we are most concerned with. It is one area that most people are assuming we control.”

Bartlam said a governmental agency does not necessarily have absolute land used jurisdiction and authority over the land within its borders. He explained, “The issue goes back to a 1962 [California] Attorney General opinion which in part states that cities and counties are mutually exempt from each other’s building and zoning ordinances when they are acting in government or proprietary activity. So, the City of Industry would be responsible for entitling the solar farm. They still have to do appropriate environmental review, which we would monitor closely.” The City of Industry would likely, though not necessarily, have less ability to dictate the terms and density of residential development on the property, Bartlam said. “The question about residential development is an interesting one. I have raised the possibility that Industry could argue it’s a ‘public purpose,’ particularly with the legislature spending so much time on housing recently.” Bartlam’s allusion was to legislation now being contemplated in Sacramento that would take away from local governments land use and zoning authority on “public purpose” residential projects intended for low- and medium-income homebuyers.

Bartlam took issue with Mitchell’s suggestion that he was intent on seeing the property developed and that the City of Chino Hills or its officials stood to in any way profit by such an eventuality.

“My personal preference is to see the property remain as is,” Bartlam said. “That said, the general plan of the city is the official document governing land use. The city council and I cannot formally say we want something different, as that can be seen as preempting the mandated review process and subject the city to an inverse condemnation claim, as Ms. Mitchell well knows.” With regard to standing by the land use and zoning standards that are in place, Bartlam asked, “How does the City of Chino Hills profit? The City of Chino Hills is not concerned about tax revenue coming from the property. Our share of property tax is extremely low. As it is, we receive a pittance of the property taxes paid by Industry on the site and are fine if that continues in perpetuity.”

Bartlam insisted that the City of Chino Hills was forthrightly, through the legal and procedural means available to it, working to mitigate to the degree possible the impacts of the development scheme the City of Industry is proposing. He said this had to be effectuated within the confines of the law and with obeisance to the City of Industry’s rights as the property owner. “It’s interesting that former council member and attorney Mitchell is suggesting we can just change the zoning. She never suggested such a move when she was on the council. As she knows, the city cannot reduce the value of the property without compensation. An inverse condemnation action from the City of Industry would surely follow. Moreover, State law prohibits jurisdictions from ‘downzoning’ residential property without replacing those units elsewhere in the city.”

Bartlam said Mitchell’s claim that initiating residential development on the Tres Hermanos Ranch property within the limitations of the current zoning would lead to a future uprating in the zoning and more aggressive development there was “misleading.” He said, “Measure U still would require a vote if the general plan is amended to increase the number of units.”

Both Chino Hills and Diamond Bar officials remain unapologetic over the review of the $41.65 million sale of Tres Hermanos Ranch to the City of Industry they have requested of the California Department of Finance. That agency, based in Sacramento, had made no findings at press time.

On the Chino Hills website, officials stated with regard to the solar project, “There is no roadmap for a project of this nature: one city (Industry), building a solar farm (a public benefit) in other cities’ jurisdictions (Chino Hills and Diamond Bar). There is very little case law to indicate the level of jurisdiction or control that the cities of Chino Hills and Diamond Bar may exercise in reviewing a project of this nature. It’s time for residents to pay attention. Do Chino Hills residents want a massive solar farm in the City of Chino Hills which continues north into Diamond Bar? Can a massive 444-megawatt solar project, one of the largest in California, be ‘unobtrusive?’ The Desert Sunlight solar project near Joshua Tree is a 550-megawatt project on 3,800 acres in the open desert. Would Industry’s proposed solar farm consume nearly 2,450 acres? Could this project truly protect open space and create recreation space for the public? Is a solar farm preferred over limited residential (208 agricultural ranch 5-acre lots, 467 units) and commercial (15 acres) development on property that always included some level of rights for the property owner to develop? It’s time to decide. As for the City of Chino Hills, we will continue to ensure that Industry and the oversight board are following the law in the actions they take. We will continue to press Industry for specifics on their solar farm project. The City of Chino Hills would prefer to leave the land as open space. However, the only way for the land to remain as is, is for the landowner to agree to leave it as is. The only way the City of Chino Hills could prevent anything from happening on the land is to buy it for the apparent sale price of $41.6 million.”

With regard to the development of Tres Hermanos Ranch, Industry City Manager Paul Philips, while deflecting questions about specifics, told the Sentinel, “The City of Industry is looking forward to exploring options for the land dedicated to open space, recreational space such as hiking trails and exploring public purpose projects that will benefit our region.”

Bartlam said, “In response to Mr. Phillips, I would ask him, ‘If your “plan” is for open space and hiking trails, why be so secretive? Why have you spent over $14 million “exploring?”’ Additionally, I would look to Industry’s history. The City of Industry was prepared to spend $100 million of taxpayer dollars for the property. It is time for them to be transparent as to their ultimate scheme. If anyone believes that they have suddenly found religion and are doing this out of respect or benefit for the region, then they may want to look at swamp land in Florida for sale… Finally I would say that if people are wondering who they should trust, look at the facts. The City of Chino Hills has over 3,000 acres of permanent open space we own and maintain. The City of Industry does not even have a park for their 200 residents to enjoy. If the City of Industry was serious about reducing traffic and congestion, they would not be decimating 650 acres at I-57 and Grand Avenue today in preparation for millions of square feet of industrial buildings. Their comments are hypocritical at best.”

The city is doing its part, Bartlam said, indeed all that it can, to either attenuate the development of Tres Hermanos Ranch or head it off completely. The most surefire way of achieving complete preservation of the ranch as it is or as dedicated open space is to acquire it and designate it as a preserve, he said. Chino Hills and Diamond Bar have discussed the possibility of combining their financial wherewithal and joining with others equally committed to preventing the development of the ranch to do just that. “If Ms. Mitchell was serious about preserving the property as open space, then she should be arguing for the purchase. She should be willing to open her check book and chip in to buy it,” Bartlam said.

Mitchell responded, “If the city council and the city manager want the residents of Chino Hills to have trust in them, they need to change the zoning on that property. They can give any excuse or explanation they want, but the city council has the authority to modify that., What it comes down to with Tres Hermanos is right now we need action, not words.”

-Mark Gutglueck

Upland Police Chief, At Odds With Nearly Four-Fifths Of His Officers, Resigns

Brian Johnson’s two-and-one-half year tenure as Upland police chief is at an end.

The atmosphere surrounding his exodus is radically different from the air of confidence that attended his assumption of the leadership of the department in March 2015.

Many in the Upland community hailed Johnson’s hiring at the time it occurred, characterizing him as a “cop’s cop,” whose career with the much larger, more prestigious, more sophisticated, more cosmopolitan and more storied Los Angeles Police Department would add dimensions to the smaller and parochial Upland PD. And Johnson appeared to have a genuine affinity and deep concern for the officers he commanded. On the evening of his introduction to the community at a March 2015 city council meeting that took place technically before he was officially police chief, a report of an injury to an officer came in and Johnson made a hurried departure into the field to ensure assistance was rendered, delaying only long enough to apologize for his abrupt leaving with a terse explanation of urgency. Upon assuming the post of police chief, Johnson initially earned kudos and appreciation from a cross section of residents and the business sector for stepping up patrols and the visibility of the department’s officers.

Johnson, however, was the first Upland police chief who had not promoted from within the ranks since Eugene Mueller, who would later go on to become San Bernardino County sheriff, was persuaded to leave his position as a captain with the Pasadena Police Department to take on the position of top cop in Upland in 1941.

Thus, Johnson was foreign to much of the culture and tradition within the Upland Police Department from the outset, and with the passage of time the degree to which he was out of step with the men and smaller complement of women he was commanding became more and more apparent.

The recruitment drive that brought Johnson to Upland was launched in 2014 with the looming retirement of Jeff Mendenhall. After Mendenhall’s departure in December 2014, Captain Ken Bonson, a 30-year veteran, had assumed the position of acting police chief. Bonson had been in the running to accede to the position of chief, and remained as captain in the immediate aftermath of Johnson’s hiring. A year after he was passed over in favor of Johnson, Bonson retired. Bonson’s exit marked the beginning of a wave of departures of experienced and advanced officers during the second year of Johnson’s primacy with the department. That mass exodus intensified as his third year as chief started this spring. To date since Johnson became chief, 28 officers left the Upland Police Department. Seven of those involved personnel who were within or very near the standard age range for retirement among law enforcement officers. The loss of 21 other officers in that time frame falls far beyond the typical two-to-seven percent annual attrition a department normally experiences in terms of lateral transfers or promotions to higher positions in other departments.

Perhaps the most noteworthy of those departures were the ones not voluntarily taken but imposed on captain Anthony Yoakum and sergeant Marc Simpson.

Yoakum was a 29-year law enforcement veteran who at one point had risen to become Johnson’s second-in-command in charge of operations. Simpson was a 23-year member of the department who was the Upland Police Officer Management Association president.

A key battleground for the heart and soul of the department was the cultural metamorphosis relating to marijuana. For nearly two decades, as in the majority of cities elsewhere in the state, the political establishment in Upland had resisted accepting the new ethos that had its rise with the passage of Proposition 215, or the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, which allowed marijuana to be used for medical purposes by those obtaining a prescription. Upland had maintained ordinances prohibiting the operation of dispensaries in the city and had spent a considerable amount of money over the years on enforcement efforts to keep ones that cropped up shuttered, as well as on legal fees against the more persistent medical marijuana purveyors who had the sophistication and the financial wherewithal to remove the issue to the courts. The city was stymied by two of those cannabis kingpins – Randy Welty and Aaron Sandusky, the operators, respectively, of the Captain Jacks and G3 Holistics dispensaries in Upland. Well before Johnson arrived in Upland as police chief, both Welty and Sandusky managed to keep their operations up and running while their medical marijuana business competitors in Upland consistently, after either short or medium term runs, would be closed down. At last, after consistently losing in their legal efforts against Sandusky, city officials made a breakthrough when they succeeded in getting the federal government – in the form of the Drug Enforcement Agency, the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office – to unleash their firepower on him. In 2012, Sandusky was prosecuted in Federal Court, convicted and given a ten-year prison sentence, which he is yet serving.

It was against that backdrop that Johnson came into Upland. Relatively early on, he came to understand that three members of the city council as it was then composed – mayor Ray Musser, councilwoman Carol Timm and councilman Glenn Bozar – were intent on holding the line against marijuana liberalization. In an effort to please them, he angled to use the police department’s authority to help hold that line. In 2016, for example, when advocates of medical marijuana availability in Upland began circulating a petition to legalize marijuana sales in the city, Johnson detailed the department’s detective bureau to monitor the signature gatherers and give them the third degree if the opportunity presented itself. Many of the officers felt such an approach bordered on or actually crossed the line into interfering in the political process. At the same time that the pro-medical marijuana availability petitioners were active on the doorsteps of Upland homes and in the parking lots of local shopping centers, a statewide initiative – Proposition 64 – aimed at legalizing marijuana for recreational purposes had been put on the ballot. Ultimately, Proposition 64 would be approved by California voters. Simultaneous with Proposition 64’s success statewide, it had failed with voters in Upland that November. Johnson took that as a signal to continue with the department’s efforts to shutter the dispensaries that continuously sprouted at new locations within the city.

For many of Upland’s officers, including ones who earlier in their careers had enthusiastically involved themselves in enforcement of the penal code relating to the prohibition of marijuana, an element of the absurd had crept into the perpetuation of the die-hard effort to eradicate marijuana clinics in the face of a two-decade old law that allowed marijuana use for medical purposes and the more recent passage of Proposition 64, which essentially ended, at least in California, marijuana’s run as an illegal narcotic and transformed it into a legally and socially acceptable intoxicant on the order of beer and wine. To them, the department’s policy was tantamount to swimming against the tide of history. And in an age of austerity with the drop off in revenue coming into government in general and budgetary and staff cutbacks to the police department, a growing number of officers felt it was time to put the department’s limited resources to work on other areas relating to crime in the city rather than chasing after the coming generation of cannabis entrepreneurs, whose numbers would eventually be winnowed and profits diminished through the principal of onerous competition among themselves.

Johnson, however, did not quite see it that way. One of the duties that had been entrusted to the department shortly before his arrival was responsibility over the city’s code enforcement function. He had taken the community’s pulse and it was clear a majority of Uplanders wanted their city to remain off limits to the marijuana profiteers. He saw that as authorization to double down on the marijuana clinic eradication effort. It would be one such undertaking, which Johnson somewhat inexplicably sought to carry out on his own, that ultimately, hindsight now reveals, was the catalyst for the series of events over the next nine months that led to his resignation as police chief.

On January 18, 2017 officers, with Johnson monitoring the operation, served a warrant at a dispensary at 1600 W. 9th Street. All marijuana, cash, weighing devices, display shelves, equipment and office supplies on the premises were confiscated. The following day, however, the dispensary was back in operation. Another warrant was obtained and the plan was to serve it either on January 25 or 26, the following Monday or Tuesday, when manpower was available. Impatient with that delay, Johnson on January 21, 2017 went to the dispensary unassisted and without notifying any of the officers on duty or dispatch of his intentions, detained everyone inside at gunpoint and ordered them to the ground. He then called the department, requesting assistance. Johnson was unable, however, to give his correct location and was only able to say he was at 9th and Benson. He could not leave the inside of the dispensary, as the dispensary’s entry and exit were controlled, as is common with commercial cannabis operations, by an electronic locking door manually controlled by an armed security guard. When the first responding officer, Anthony Kabayan, arrived on the scene, he was not able to gain entry into the business. Kabayan then initiated an effort to kick the door down. Ultimately, Johnson was able to have the door opened, allowing the arriving officers into the business. Johnson had at least six people – customers and employees of the dispensary – detained, handcuffed, transported to the Upland Police Department headquarters and put into holding cells and then transported to the West Valley Detention Center where the county’s jailers initially resisted booking them because they had not been arrested on a bookable offense. Ultimately, Johnson was able to convince the sheriff’s employees to accept the prisoners into the detention center on a municipal code violation, which technically could not be used to justify the incarceration and which ultimately the district attorney’s office declined to prosecute. This has left the city subject to a potential false arrest lawsuit from at least six of those individuals. Subsequently, in an apparent effort to get the city out from underneath the liability of those yet-to-be-filed civil suits, Johnson began to cast about for some justification of the arrest that could be applied after the fact. He attempted to do this roughly a month after the arrests by requisitioning the laptop computer and DVR seized from the dispensary that were part of the surveillance system of the premises. He then ordered the department’s information technology specialist to make copies of the video contents and computer data. That, however, constituted an illegal search under the Fourth Amendment and a violation of SB 178, a 2016 California law governing the search of electronic items. A separate search warrant was required to search those items and could not have been obtained because the original crime was a misdemeanor and not a felony.

For several of the department’s officers, Johnson’s action on January 21 and its aftermath was what one of those officers described as “the last straw,” in that Johnson’s actions violated officer safety protocol, did not take into account that since he was not easily identifiable as a police officer that the on-site security guard could have thought that the business was being robbed, thus resulting in an armed confrontation, and that he placed the officers responding to the location and citizens at danger. With the three highest ranking department members below Johnson who were involved in the response to the dispensary – a patrol sergeant, the watch commander and the patrol division commander – concurring, a collective decision involving multiple officers was made to proceed with an official complaint against Johnson. That complaint, in slightly different format, was lodged by at least three department members in early February. Detective Lon Teague, the president of the Upland Police Officers Association, played a central role in taking the issue forward, ultimately to Upland’s acting city manager, Martin Thouvenell. Thouvenell was himself a former Upland police chief, and was one if the three panelists that evaluated the applicants to replace Mendenhall in late 2014 and early 2015, which ultimately selected Johnson.

Upon learning that Teague had gone out of department channels in lodging the complaint – channels that would have ultimately reached Johnson and have required that he pass judgment on his own action – Johnson suspended Teague, pending an internal investigation. At that point, captain Yoakum, then the department’s second ranking officer behind Johnson as the operations commander, and Simpson, the department’s senior sergeant and the president of the Upland Police Management Association, moved to back Teague. As both Yoakum and Simpson were considered members of the department’s management team, Johnson deemed their action to be insubordination. They too were suspended.

In the meantime, Thouvenell, at an expense to the city of $30,000, had a management consultant look into the complaint against Johnson. That inquiry was completed by late May.

The Sentinel has acquired an internal city communication from Thovenell to one of the complainants. Dated June 1, 2017, it states, “The complaint(s) set forth alleged that chief of police Brian Johnson committed a violation of California Penal Code Section 1546.1 (SB 178) when material contained on a DVR was viewed without first obtaining a search warrant. Based on the allegations provided in these documents, a formal investigation was conducted. Pursuant to California Penal Codes section 832.7(e))(1), you are hereby notified that this allegation was sustained.” The communication continues, “Pursuant to California Penal Code Section 832.7(a) concerning the confidentiality of peace officer personnel matters, the city is precluded from providing additional details of the investigation or the nature of any discipline which may have been imposed.”

The Sentinel has learned from a reliable source that Thouvenell imposed on Johnson what was referred to as “informal counseling.”

Johnson at that point remained police chief, with what was essentially full autonomy over the department.

For slightly more than six months, the investigation of Teague was ongoing, and the suspensions of Yoakum and Simpson continued. During that time, all three remained in limbo and on paid leave, representing a cost of roughly $270,000. Taken together with the $30,000 spent on the management consultant’s inquiry into Johnson’s action, the cost to Upland’s taxpayers growing out of the January 21 incident approximated $300,000 monetarily, and the loss of Yoakum’s, Simpson’s, and Teague’s services throughout the six-month plus duration. Ultimately, it was determined that while Teague’s action had deviated from the normal protocol and lines of authority within the department and had “improperly” challenged Johnson’s judgment and authority, his status as the department rank and file’s union authority would make firing him highly problematic. He was given a 40 hour suspension as his official discipline with a notation of reprimand by the chief placed into his personnel file.

Even though Yoakum and Simpson outranked Teague, they were in an even more delicate situation. Indeed, as members of the department’s management team, they were answerable to the police chief and subject to his discretion. Both were charged with disparaging the chief of police and making unauthorized disclosures about the investigation. Given the nature of the chain of command and their direct links to Johnson, it was Johnson’s judgment that the working relationship he had with both of them was irrevocably sundered. On that basis, they were terminated earlier this month.

With Yoakum and Simpson’s sackings and Teague’s reinstatement pursuant to his 40 hour suspension, the paralytic stasis that had persisted within the Upland Police Officers Association came to a close. The Sentinel was informed earlier this week that the Upland Police Officers Association had called for, and held, a vote of no confidence against Johnson. The Sentinel was told that 78 percent of the association voted against Johnson or “no confidence.” Ten percent voted that they yet had “confidence” in Johnson’s leadership of the department. The balance, some 12 percent, rendered a verdict of “undecided.”

On Wednesday, a former law enforcement officer with a direct pipeline to several members of the department told the Sentinel that with regard to Johnson, “Word on the streets is he’s a ‘Dead Man Walking’ and will submit his resignation ‘soon.’”

Early Friday morning, Johnson announced to his command staff that Monday, October 30, will be his last official day on the books.

Persistent efforts to contact Johnson this morning and early afternoon prior to press time reached only the recording device on his desk telephone and the day watch commander, who told the Sentinel he had attempted to relay the interview request to Johnson but had been unable to reach him by mid-afternoon.

–Mark Gutglueck

Miffed With Postmus’ Testimony, DA Now Seeking Long Sentence

The legal fate of Bill Postmus, whose meteoric rise in San Bernardino County politics in the early 2000s was matched in intensity by the plunge that followed his implosion and crash to earth in a series of scandals that rocked the county and the Republican Party to the core, will not be fully determined at least until January.

Postmus, 46, was in court early this morning before Judge Michael A. Smith for possible sentencing on charges against him which were lodged in 2009 and 2010 and to which he pleaded guilty in March 2011. His sentencing has been held in abeyance since then as part of the plea agreement he entered into in which he committed to cooperate with prosecutors in their prosecution of his alleged accomplices and co-conspirators. In the immediate aftermath of his guilty plea Postmus met the prosecutors’ expectations, testifying as the star witness before a grand jury in April 2011 which was looking into a $102 million settlement conferred upon the Colonies Partners in November 2006 and the exchange of money that took place between the Colonies Partners and county officials within the ensuing eight months. That $102 million payout ended legal wrangling between the Colonies Partners and the county which related to disputes the company had with the county flood control district over drainage issues at the Colonies at San Antonio residential and Colonies Crossroads commercial subdivisions in northeast Upland. Following Postmus’ testimony, which was augmented with the testimony of more than 30 others, that grand jury in May 2011 handed down an indictment of Colonies Partners co-managing principal Jeff Burum; Postmus’ former board of supervisors colleague Paul Biane; former San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies union president Jim Erwin; and Mark Kirk, who had been the chief of staff to another of Postmus’ board colleagues, Gary Ovitt. According to the 29-count indictment, Burum had conspired with Erwin to threaten and blackmail Postmus and Biane into settling the lawsuit. The indictment alleged Erwin prepared but ultimately withheld “hit piece” mailers that targeted Postmus, who was then the board of supervisors chairman as well as the chairman of the San Bernardino County Republican Central Committee, and Biane, then the vice chairman of the board of supervisors as well as the vice chairman of the same central committee. Those mailers, according to prosecutors, took as their subject matter Postmus’ homosexuality and methamphetamine addiction and Biane’s financial travails which had him on the brink of bankruptcy. After Postmus, Biane and Ovitt on November 28, 2006 voted to enter into the $102 million settlement, the indictment alleged, between March 2007 and the end of June 2007, the Colonies Partners endowed political action committees controlled by Postmus, Biane, Erwin and Kirk with $100,000 each. Prosecutors maintained the donations to Postmus and Biane were bribes provided in return for their votes in support of the settlement and that the $100,000 donation to Kirk’s political action committee was likewise a bribe made in exchange for his having delivered Ovitt’s vote in favor of the settlement. Kirk as his chief of staff, had been Ovitt’s primary political advisor.

Postmus’ vote in favor of the settlement had come when he was a lame duck as a member of the board of supervisors. Three weeks previously, on November 7, 2006, he had been elected county assessor. In 2007, after he assumed the position of assessor, he upped the number of assistant county assessors from one to two and installed both Erwin and a close friend and political associate, 23-year-old Adam Aleman, into those positions. In the ensuing 18 months, Postmus slipped further into the morass of drug addiction. The county assessor’s office, into the management echelon of which Postmus had made a series of no fewer than 11 political appointments of friends and associates who had virtually no real estate, appraising or taxation policy/regulation expertise, became a hotbed of partisan political activity, promoting the Republican Party, Republican causes and certain Republican candidates. An investigation into this activity by the district attorney’s office began in 2007, and in 2008 events overtook Aleman, who was called before a grand jury to be questioned about the goings-on in the assessor’s office. Panicked, Aleman had an office employee alter some internal assessor’s office documents, destroyed the hard drive in a county-issued laptop and then lied in his testimony to the grand jury. Ultimately, all of these actions were detected by district attorney’s office investigators and Aleman was arrested and charged with a variety of crimes in July 2008. By November 2008, he had begun cooperating with prosecutors, including recording conversations with others, among them Postmus, helping at first to assemble a case against members of the assessor’s office engaged in political activity on county time using county facilities that was unrelated to the assessor’s official function. Subsequently, he provided information to district attorney’s office investigators with regard to events prior to and after the $102 million settlement of the litigation brought by the Colonies Partners against the county, which he said involved efforts to intimidate, threaten, and blackmail Postmus and Biane to extort from them support of the lawsuit settlement, followed by the provision of kickbacks after the settlement, disguised in the form of political donations.

Aleman pleaded guilty to four felony charges in July 2009 and agreed to testify against any others involved in illegal activity about which he had knowledge. Based in large measure on information supplied by Aleman, the district attorney’s office in 2009 charged Postmus with misuse of his authority as assessor in allowing the office to be used for unauthorized purposes and with misappropriation of public funds. In February 2010, again based to a considerable degree on information provided by Aleman, the district attorney’s office in conjunction with the California Attorney General’s Office charged both Postmus and Erwin with conspiracy, fraud, involvement in an extortion and bribery scheme, misappropriation of public funds, engaging in a conflict of interest as public officials, tax evasion and perjury related to the Colonies Partners lawsuit settlement and its aftermath.

Postmus, who had been driven to resigning as assessor in February 2009 in the wake of public revelations about his drug use, by early 2011 was running out of options and money. At that point, he entered into the aforementioned plea arrangement on the assessor’s office corruption case, the Colonies Partners lawsuit settlement case and a separate charge relating to drug possession, a total of 14 felonies and a single misdemeanor.

Since 2011, Postmus has been a free man despite his conviction, though the resolution of his criminal case yet hung over his head, and the adverse publicity had ruined any prospect that he might remain in politics. His guilty plea on the conflict of interest charge legally prohibits him from holding elective office.

In January, the criminal case against Burum, Biane, Erwin and Kirk went to trial after numerous motions, rulings, appeals and delays. A total of 39 witnesses were heard from during the course of the case. The lion’s share of those testified during January, February, March and April, setting the table for Postmus and Aleman, who were the star witnesses, to begin their testimony in May. During his first three days of testimony under direct examination from May 1 through May 3, Postmus replicated the key elements of the prosecution narrative. In the latter half of 2006, Erwin, working on behalf of Burum and the Colonies Partners, Postmus testified, had threatened to expose elements of both his and Biane’s personal lives in an effort to persuade them to support the settlement. And Burum had promised to support him in either or both future political and business endeavors once the settlement was out of the way, he said. Moreover, Postmus said, he believed the $102 million paid out to the Colonies Partners was ridiculously more than the development company was due. The threats and promises of reward, he testified, along with the desire to put the whole thing behind him prompted the settlement. And after the settlement was in place, Postmus testified, the Colonies Partners had come through with $100,000 for him in the form of two separate $50,000 donations to political action committees he had control over.

But thereafter, the defense was given an opportunity to cross examine Postmus and controvert the prosecution’s version of events he had supported. Particularly under the withering questioning of Burum’s attorney Jennifer Keller, Postmus began to go sideways, responding positively to the suggestions in Keller’s questioning which offered alternate and even diametrically conflicting descriptions of events he had described. On the witness stand, Postmus moved toward adopting Keller’s stated theory that much of what he was testifying to had been planted in his memory by unscrupulous district attorney’s office investigators who had taken advantage of him, his legal vulnerability and his drug-addled state by interrogating him over and over while inculcating in him the prosecution’s narrative of events with their questions. Contradicting his testimony under direct examination, Postmus said he did not consider the $100,000 in contributions to his political action committees from Colonies Partners in 2007 to have been bribes, and that there was no quid pro quo inherent in his settlement vote and the contributions. He claimed any confusion about what had occurred was because “my mind is kind of messed up” from his use of drugs.

After eight months, the trial drew to a close with Burum, Biane and Kirk being exonerated on all of the charges against them and Erwin’s jury deadlocking, followed by the district attorney’s office dismissing the case against Erwin. At the time of that dismissal, district attorney Mike Ramos stated publicly, “Bill Postmus’ unexpected testimony on cross-examination at the last trial conflicted with his grand jury testimony, his statement to the FBI, and multiple interviews with the district attorney’s office.”

Ramos’ statement presaged what occurred this morning, when instead of acquiescing to having Judge Smith adhere to the language of the plea agreement which called for dismissing eleven of the felony charges against Postmus and taking into consideration Postmus’ testimony to arrive at a determination as to what his sentence would be, Supervising San Bernardino County Deputy District Attorney Lewis Cope asked for Smith to refer Postmus’ case file to the Riverside County Probation Department for review and sentencing recommendations. The matter is going to the Riverside County Probation Department because Postmus, who was formerly one of the most powerful political figures in San Bernardino County, oversaw and approved budgetary allotments for the San Bernardino County Probation Department, and officials want to avoid any chance of the recommendation on sentencing being influenced by that.

Based on these developments, and Ramos’ statement at the conclusion of the trial, it appears that the district attorney’s office is seeking to have convictions on all of the charges against him reinstated. Under that plea agreement, Postmus was convicted of all 15 of the charges on the proviso that based upon his cooperation, all but three of the 14 felony convictions would be vacated, and the maximum sentence he would receive would be six years and eight months, with the possibility that the prosecution would recommend that he be given straight probation with no actual prison time. Sentencing remains within the discretion of the judge. The judge in Postmus’ case, Michael Smith, was the trial judge in the case tried against Burum, Biane, Erwin and Kirk. Thus, Judge Smith has sufficient perspective to make his own conclusion as to Postmus’ credibility on the witness stand and whether he indeed lived up to the terms of the plea arrangement he made with prosecutors in 2011.

The case file the Riverside County Probation Department will be provided on Postmus will consist either primarily or wholly of material generated or vetted by the San Bernardino County District Attorney’s Office, which is still smarting from the failure to win any convictions in the matter arising out of the Colonies Partners lawsuit settlement other than the pleas from Postmus.

Judge Smith gave indication that he anticipated having to mete out Postmus’ punishment based on the prosecution’s contention that Postmus had failed to live up to the terms of the plea agreement and in the face of contrary contentions by Postmus’ lawyers, Stephen Levine, who is representing Postmus with regard to the Colonies Partners lawsuit settlement, and Richard Farquhar, who represents him with regard to the charges stemming from his tenure as assessor.

“That [the sentencing recommendation] might be contested,” Smith said, with some degree of understatement. Judge Smith then said that the Riverside Probation Department should not count on him to assist it in giving his size-up of how truthful Postmus had been on the witness stand prior to sentencing.

Noting that both the court and the probation department will be “interested in knowing counsels’ perspective on whether the terms of the agreement were fulfilled,” Smith said, “Were probation to inquire of me, I would not give them any response. That is because I would have to decide [the question of whether Postmus had indeed cooperated fully and entirely with the prosecution].” Smith said accordingly, “It would not be appropriate for me to comment.”

The probation department is to complete its report and Cope, Levine and Farquhar are to make written submissions, known as sentencing memorandums, to the court. Smith ordered Postmus to return to his courtroom on January 19, at which point sentencing is to take place or further hearings or arguments on the matter will be either heard or scheduled.

After the hearing, Levine told the Sentinel, “Mr. Cope wants to throw him [Postmus] under the bus.” Levine said that he is uncertain as to how aggressive Cope, who saw firsthand the pressure Postmus was subjected to during Keller’s cross examination, will be in asserting Postmus failed to abide by the terms of his plea deal when he authors his sentencing memorandum. Levine, who characterized Cope as “a decent guy,” said nonetheless that Cope took his marching orders from district attorney Mike Ramos.

Ramos is facing reelection next year and it is anticipated that his political opponents will make an issue of the failure to get a conviction in the recently concluded Colonies Partners lawsuit settlement case, as the matter has been widely referred to as one of the most important prosecutions carried out by Ramos’ office in his more than 14 years as district attorney.

Jurors interviewed after the verdicts were returned indicated that Postmus’ hedging of his testimony was a factor in their acquittal votes, but they said that Aleman’s credibility was a major consideration as well. Aleman was subjected to an even more brutal onslaught during his cross examination by defense attorneys than was Postmus. Though he was shown to have gotten some particulars such as dates and locations of meetings that took place between himself and some of the defendants wrong, Aleman remained relatively faithful to the narrative staked out by prosecutors in the indictment, and on occasion grew contentious with the defense attorneys. This was in stark contrast with the manner in which Postmus appeared to come to an accommodation with the defense attorneys who were cross examining him. For that reason, it does not appear that the prosecution will move to revoke the terms of the plea agreement Aleman entered into in 2009.

Other witnesses were problematic for the prosecution during the trial. Supervisor Josie Gonzales confused 2005 with 2006 in recounting a near encounter she said she had with Burum in China prior to the settlement vote, which she testified was part of a pattern of her being unduly pressured to approve the lawsuit settlement. Matt Brown, who had been Biane’s chief of staff during the run-up to the settlement in 2005 and 2006, had been counted upon by the prosecution to offer damning testimony during the trial, recapitulating elements of his grand jury testimony. Brown, who had created the political action committee through which the $100,000 donation from the Colonies Partners to Biane alleged to be a bribe had been provided after the settlement and who in 2009 and 2010 used a hidden recording device in an unsuccessful effort to capture utterances from Biane implicating himself in the alleged bribery scheme, proved highly testy during his questioning on the stand, claiming he had no recollection of numerous events nor of several of his previous statements before the grand jury.

Prosecutors have no leverage on either Brown or Gonzales, however, as they were never charged with crimes. In the case of all of the witnesses, including Postmus, the passage of a decade between the events in question and their testimony is seen as a plausible reason for lapses in memory or confusion with regard to dates, times, places and facts. Postmus repeatedly claimed that his memory of events had been impaired by his drug use. Nevertheless, prosecutors believe Postmus in large measure malingered memory loss and that he has demonstrated remarkable clarity and mental acuity with regard to many other events and activities, both related and unrelated to the Colonies case. They believe internal inconsistencies in his testimony demonstrate he failed to meet the requirement laid out in his plea arrangement that he cooperate fully with the prosecution and testify accurately and to the best of his recollection at trial.

Cope said he was not at liberty to comment on anything relating to Postmus’ case due to his office’s policy of not discussing ongoing cases outside the courtroom.

-Mark Gutglueck

Highland And County Dinged For Militating To Favor Incumbents In 2016 Council Races

San Bernardino County Superior Court Judge David Williams has entered a judgment against the City of Highland and San Bernardino County in a legal action brought against them by 2016 Highland Ward District 4 city council candidate Frank Adomitis, who alleged the city and the county loaded the dice against political outsiders in last year’s election.

In particular, it appears, Williams found credible Adomitis’ contention that the city and the police/sheriff’s department militated in favor of John Timmer and Larry McCallon, incumbent councilmen running in the election who emerged victorious over, respectively, three challengers and a single challenger.

In the 2016 election, Highland, its political institutions and its office holders found themselves under an uncommon attack of historic significance. In the light of Williams’ ruling, it appears city officials reflexively sought to insulate the city’s powerful insiders from having to participate in an open and unbiased political process.

Traditionally since its 1987 founding, Highland’s elected leaders – the members of the city council from among whom they designated one of themselves on a rotational basis to serve as the city’s mayor – were elected in at-large elections in which all Highland residents of the age of majority were at liberty to run.

In 2014, however, Highland resident Lisa Garrett, who claimed Latino lineage, publicly asserted that the city’s Hispanic population was not properly represented given that approaching half of the city’s residents – 48 percent of its 53,104 citizens – are Hispanic and the city had never elected a Latino to the council. Represented by the Lancaster-based R. Rex Parris Law Firm, Malibu-based Shenkman and Hughes, along with attorney Milton C. Grimes of Los Angeles, Garrett filed a lawsuit, alleging that the city was violating the California Voting Rights Act of 2001 by continuing to hold at-large elections and not switching to a ward system whereby minority voters would stand a greater prospect of electing one of their own ranks to office.

In response to the lawsuit, the city council directed Highland City Attorney Craig Steele to draft documents that were later enacted by the council, placing a measure on the ballot in the November 2014 election, Measure T. Measure T would have divided the city into five voting districts. Ward district elections would have begun in 2016 with two districts. The remaining three districts would have been subject to the 2018 election, according to the terms of the measure. Two of those districts would have contained a majority of Hispanic voters, and a third ward would have been populated by residents, more than 40 percent of whom were Latino. On election day in 2014 and by absentee ballot, 6,655 of the city’s voters participated, with 43.01 percent, or 2,862 voting in favor of Measure T and 3,793 or 56.99 percent rejecting it.

Following that vote, Garrett’s lawsuit proceeded and the city sought to assuage the demand by proposing to allow cumulative voting, in which each voter is given one vote for each contested position and is allowed to cast any or all of those votes for any one candidate, or spread the votes among the candidates. When the matter went to trial, despite making a finding that the socioeconomic based rationale presented by the plaintiff’s attorneys to support the need for ward elections was irrelevant and that the plaintiff’s assertion that district voting was the only way to cure the alleged violation of the Voting Rights Act was false, San Bernardino Superior Court Judge David Cohn mandated that Highland adopt a ward system.

In this way, the 2016 election marked a major departure from the way things had been done previously in Highland. Up to that point, the City of Highland had evinced a substantial degree of stability in its politics, with its incumbents being consistently reelected.

In the 2016 election, two of the city’s longtime incumbents, Jody Scott and San Racadio, opted out of running. In the four contested contests under the newly implemented ward system, incumbents Larry McCallon and John Timmer did run.

Timmer, who had been zoned into the city’s Fourth District, found himself beset with three challengers, Russell “Rusty” Rutland, Frank Adomitis and Christy Marin. McCallon, whose residency put him in the Fifth District, invited a single challenger, Jerry Martin. No one challenged Penny Lilburn, a resident of the Third District. The First and Second district races featured no incumbents, and a field of newcomers – Jorge Osvaldo Heredia, Raymond Hilfer and Jesus “Jesse” Chavez in the First District and Anaeli Solano and Tony Collins Cifuentes in the Second District – threw their hats in the ring.

Curiously, City Hall facilitated a public forum for candidates that featured Timmer and McCallon in the Fourth and Fifth Districts but somehow excluded their challengers. That forum also involved Heredia, HIlfer and Chavez from the First District and Solano and Cifuentes from the Second District. That event was held in a city facility, known as the community room, which also doubled as the Highland Police Department’s training room. Highland contracts with the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department for law enforcement services. In this way, the Highland sheriff’s substation is the Highland Police Department.

When Adomitis requested that the city allow the community room be utilized for a more inclusive candidate forum that would allow for a debate that included him, Rutland and Marin to participate, captain Tony DeCecio, the Highland sheriff’s substation commander and by extension Highland’s police chief, refused. DeCecio vetoed allowing the community room to be used for the forum because he did not want the department’s training facility tied up, notwithstanding that he had raised no objections to a similar event when the request had originated with the city.

Undeterred, Adomitis arranged to rent the events center owned by the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians to hold the candidates forum. In his case, Adomitis invited all of the other candidates, including McCallon and Timmer, to participate. As it turned out, neither McCallon nor Timmer, nor any of their political allies participated in the forum at the San Manuel Reservation.

It remained an open question as to whether the city’s action in keeping McCallon’s and Timmer’s challengers at bay by not having them participate in a city-sponsored forum was a calculated effort to benefit the incumbents. As it turned out, the incumbents prevailed in the election.

Timmer, with 1,998 votes or 44.69 percent in District 4 outdistanced his closest competitor, Marin, who captured 1,190 votes, or 26.62 percent. Rutland came in third with 714 votes or 15.97 percent and Adomitis trailed the others with 569 votes or 12.73 percent.

McCallon, running head to head against Martin, won with 2,655 or 58.69 percent of the District 5 vote to Martin’s 1,869 votes or 41.31 percent.

In District 1, Chavez, with 649 votes or 39.99 percent, emerged victorious over Heredia, with 569 votes or 35.06 percent, and Hilfer, who drew 405 votes or 24.95 percent.

In District Two, Solano’s 895 votes or 59 percent beat Cifiuentes’ total of 622 votes or 41 percent.

Over the last part of 2016 and the first six months of 2017, what had occurred percolated with Adomitis, who developed the belief that the institution of Highland’s city government had indeed played favorites and purposefully disadvantaged the political outsiders challenging incumbents Timmer and McCallon.

In July Adomitis filed a legal action in San Bernardino County Superior Court against the city and county.

So open and shut was the matter that neither the City of Highland nor the County of San Bernardino deigned to have an attorney – either one from the Highland city attorney’s office nor the county’s stable of in-house lawyers known as the office of county counsel – contest that matter. Rather, the city sent Nancy Wayne, its administrative representative, to represent it. The county employed one of its risk management personnel, Rick Castanon, to appear for it.

Adomitis gave Wayne and Highland and Castanon and the county a shellacking in court. Judge David Williams ordered the county and the city to pay Adomitis the $2,690 he had to spend putting on the public forum, along with $90 in litigation costs.

-Mark Gutglueck

Hesperia Mayor Russ Heading To New Orleans For Double Organ Transplant

Hesperia Mayor Paul Russ, who was handed a possible death sentence earlier this year when he learned his only kidney was failing and he had liver cancer, is soldiering on and will temporarily relocate to Louisiana next month to await a double organ transplant he hopes will prolong his life.

Russ, 57, is no stranger to dire health challenges. At the age of 12, a viral infection devastated his kidneys. In 1986, at the age of 26, he began kidney dialysis. A year later, he received a kidney transplant from his brother, Raymond. That kidney did him yeoman’s service for thirty years, twice the 15-year span typical kidney transplants remain viable.

Along the way, Russ contracted hepatitis, but treatment had rendered it dormant.

In March, he pulled a muscle and took a muscle relaxant. A metabolic reaction to the muscle relaxant activated the hepatitis C. Dazed and disoriented, he was taken to the emergency room at Desert Valley Hospital. There it was determined that the drug he was taking was not passing beyond his kidneys, to the point that he had gone into stage 4 renal failure. He was given prednisone and he recovered, relatively, to stage 3. Follow-up tests showed his kidney is failing and that he had liver cancer.

This summer, he was set to begin chemotherapy to combat the liver cancer, which would have precluded any possibility that he could get another kidney transplant, consigning him to a lifetime of dialysis.

Before actually beginning chemotherapy, he applied for a double organ transplant. He was recently informed by Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans that he has been accepted. He will sojourn there in two weeks and await the availability of the two organs he needs.

Nan Songer – Yucaipa’s Spider Woman

By Amanda Frye

Nan Songer, a self-taught naturalist, played a once well-hidden but pivotal role in the American victory in WWII.

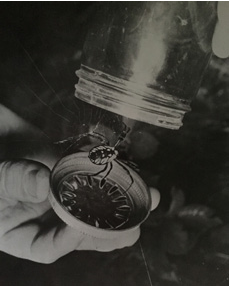

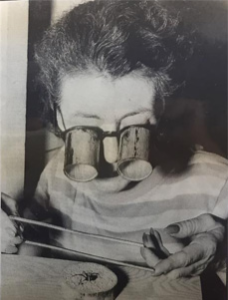

Nan Songer displays one of the creatures which fascinated her as a child and which became her life’s work and legacy.

Born Nannie Mae McCawley on May 26, 1892 in Cooksville, Tennessee to Joey Harris and Sarah Lula Hix McCawley, she was frail as a child and led a sheltered life. While she was very young she became interested in insects and arachnids, observing them in her home’s garden, where she would sit for extended periods in the sun. In high school, she studied botany and biology under the tutelage of Marie M. Meislawn.

Her brother Ridley had contracted tuberculosis and the family moved to Texas and Golden, Colorado in an effort to help with his recovery. After her family moved to Redlands, she was awarded an art scholarship to the University of Redlands in 1920, although she did not graduate from that institution.

On November 23, 1923, she married William A. “Bill” Nelson, with whom she would have two children, Elizabeth Louise “Betty Lou” on March 10, 1924 and William Donald “Billie Don” on September 23, 1925. In 1926, she lost both of her parents to influenza. She and Bill divorced sometime around 1930.

Nan subsequently met Noah H. “Bill” Songer, and they married on August 5, 1934. Songer was two decades older than she. He was devoted to her.

They resided on the North Bench on a three acre ranch at Juniper and Adams, and had a mailing address of Route 1, Box 120 Yucaipa.