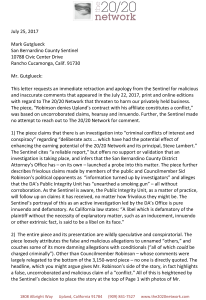

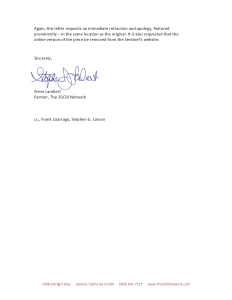

By clicking on the mages below you can access each of the pages of Steve Lamber’s demand for retraction lodged with the Sentinel.

Monthly Archives: August 2017

Upland City Councilman Sid Robinson’s Demand For Retraction

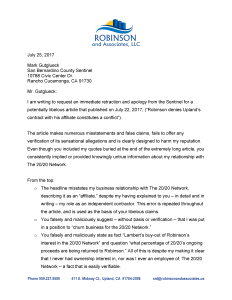

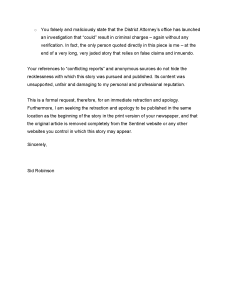

Upland City Manager Martin Thouvenell’s Demand For Retraction

Read The August 18 SBC Sentinel Here

By clicking on the blue portal below, you can download a PDF of the August 18 edition of the San Bernardino County Sentinel.

Final Arguments Begin In Historic County Political Corruption Case

By Mark Gutglueck

After six months of testimony by 34 witnesses in the Colonies Lawsuit Settlement Public Corruption Trial relating to actions that took place a decade and more ago, one of the two lead prosecutors in the matter and three of the defense attorneys this week offered widely divergent interpretations of that evidence in closing arguments. Those closing statements were initiated before the two juries which will soon begin their deliberations with regard to the four defendants.

Rancho Cucamonga-based developer Jeff Burum stands accused of conspiring with one-time sheriff’s deputies union president Jim Erwin to threaten, coerce, blackmail and extort former San Bernardino County supervisors Bill Postmus and Paul Biane to support the settlement of a lawsuit Burum’s company, the Colonies Partners, had brought against the county and its flood control district over drainage issues at the Colonies at San Antonio residential and Colonies Crossroads commercial subdivisions in northeast Upland filed in 2002. Together with Mark Kirk, who in 2006 was supervisor Gary Ovitt’s chief of staff, Burum, Biane and Erwin were named as criminal defendants in a May 2011 indictment. That indictment originally charged the four with a host of criminal acts including conspiracy, extortion-related and bribery-related acts, misappropriation of public funds, conflicts of interest, failure to report income and tax evasion. Before and during the trial, a substantial number of those charges have been dismissed. Burum and Erwin are yet charged with aiding and abetting Postmus and Biane in receiving and agreeing to receive a bribe. Biane remains charged with receiving and/or agreeing to receive a bribe under Penal Code sections 165 and 86, and engaging in a conflict of interest. Mark Kirk is faced with improper influencing of a public official and conflict of interest. Beyond aiding and abetting Postmus and Biane in receiving a bribe, Erwin faces additional charges of failing to file a tax return and of not properly disclosing his reception of gifts and other income from the Colonies Partners.

Postmus has already pled guilty to conspiracy, bribery, misappropriation of public funds, engaging in a conflict of interest as a public official and perjury. He turned state’s evidence and testified against the four defendants. Also testifying against them was Adam Aleman, who had been a member of Postmus’ staff when Postmus was supervisor and served in the capacity of assistant assessor after Postmus was elected assessor in 2006 and assumed that office in 2007. Aleman was caught up in the political corruption scandal surrounding Postmus, and he too agreed to turn state’s evidence, like Postmus testifying as part of a plea deal in return for favorable consideration with regard to his sentencing. Like that of Postmus, Aleman’s sentencing has been on hold during the duration of the Colonies trial.

According to California Supervising Deputy Attorney General Melissa Mandel, the evidence she and her prosecutorial colleague, San Bernardino County Supervising Deputy District Attorney Lewis Cope, laid out during the course of the trial, coupled with the trial testimony, provided a “bright and clear” illustration of “the contrast between what went on in this case and what we would expect to see” in the course of litigation between business entities and the county. Mandel said “secrecy and cover-up” surrounded the actions Postmus, Biane and Kirk took while the litigation was ongoing. That action included, she said, angling to obtain for Burum and the Colonies Partners a favorable outcome of the lawsuit the company was pursuing, which demonstrated their loyalty was not to the citizen taxpayers who had elected or employed them but rather with Burum, who had corrupted them through threats and blackmail and the provision of money.

“In this case, the devil’s in the details,” said Mandel. “We see lies. We see a cover-up. We see things done in secrecy. Those things don’t happen when things are on the up and up.”

Postmus, Biane and Kirk, Mandel said, “held themselves out to be” faithful public servants looking after the greater good while “secretly they were working toward one goal: to get as much money as they could into Jeff Burum’s hands for their own personal gain.”

The greater good they betrayed, Mandel said, consisted of letting the case the Colonies Partners had filed against the county be fully adjudicated in the court system.

“Trial was the best outcome,” Mandel said, to demonstrate “the shoddy construction work the Colonies had done” on a flood control basin that was at the root of the dispute between the county and the Colonies Partners. But Postmus, Biane and Gary Ovitt had chosen instead, she said, to “silence the voices that would stand up for the county,” i.e., the county’s lawyers representing the county in the lawsuit. Those lawyers were both contesting the Colonies Partners’ claims of extensive county liability with regard to the issues relating to delays of the Colonies Partners’ projects as well as working toward having other entities involved in those delays, including making sure other responsible government “agencies would pay their fair share.” Mandel said, “There was a train driven by Jeff Burum’s and Jim Erwin’s unadulterated greed, but Mark Kirk and Paul Biane weren’t supposed to be on that train. From the beginning Jeff Burum and Jim Erwin were trading money for political influence.”

Mandel said, “San Bernardino County and the Colonies [Partners] were adversaries in that lawsuit.” But Postmus, Biane and Kirk, influenced by the money Burum was handing about, she said, were militating on the Colonies Partners’ interest rather than on behalf of the county.

According to Mandel, Burum and Erwin “took over San Bernardino County the way ordinary bullies take over a schoolyard.”

Mandel said that the way in which the $102 million lawsuit payment was conferred upon the Colonies Partners to settle the case was a criminal enterprise which was evidenced by a “paper trail” which traced out “a secret flow of money” that originated with Burum and the Colonies Partners. Ultimately, Mandel said, that money lodged with Postmus, Biane and Kirk, as bribes, and with Erwin, as a reward for his part in the “scam,” all in the form of donations to political action committees the defendants had set up to receive and launder those bribes.

Burum used his wealth to drive an early opponent of the lawsuit settlement, Jon Mikels from office, bankrolling in large measure the campaign of Biane, who replaced him, Mandel said.

Burum’s greed, Mandel said, had propelled the settlement amount from a disputed $28 million in early 2004 to $77 million in March 2005 to the $102 million approved by a bare 3-2 majority of the board of supervisors in November 2006.

Mandel said Burum employed Erwin as a cat’s paw to carry out his depredations. Erwin at that time was no longer the president of the sheriff’s deputies union, the Safety Employees Benefit Association, known by its acronym, SEBA, and had moved on to become SEBA’s executive director. From that position, Mandel asserted, Erwin had used SEBA’s political action committee’s account to launder – that is to hide the true origin of – money provided by the Colonies Partners that went to Biane.

In the spring and early summer of 2007, after the settlement was voted upon and $102 million had come the Colonies Partners’ way, Burum made $400,000 in contributions divided equally to political action committees (PACs) controlled by Postmus, Biane, Erwin and Kirk. The Inland Empire PAC and the Conservatives for a Republican PAC, each controlled by Postmus, received $50,000 each. The San Bernardino County Young Republicans, controlled by Biane, received $100,000. The Alliance for Ethical Government, which Kirk controlled, received $100,000 from Burum. And Erwin in March 2007 set up a PAC, the Committee for Effective Government, which likewise was provided with a $100,000 check from the Colonies Partners signed by Burum.

Postmus, Kirk and Erwin created those PACs in the aftermath of the settlement. Members of Biane’s supervisorial staff set the San Bernardino County Young Republicans PAC up in 2004, nearly two years before the settlement vote. Nevertheless, Mandel said, Biane had utilized that PAC to hide the origin of money he was receiving from Burum and the Colonies Partners from the inception. This is an indication that all along Biane was anticipating receiving a “big payoff” for assisting in securing a settlement on the Colonies Partners’ lawsuit against the county.

Erwin, by virtue of his control over SEBA, had facilitated “secret” deliveries of money to the elected co-conspirators involved, Mandel said, laundering those donations so that the politicians militating on Burum’s behalf could not be directly tied to him or the Colonies Partners. On December 10, 2004, Colonies Crossroads contributed $8,000 to SEBA. Seventeen days later, on December 27, 2004, SEBA contributed $5,000 to the San Bernardino County Young Republicans.

In addition, Mandel said, Burum had made contributions – ones substantially smaller than the $100,000 Biane’s PAC received in 2007 – to the San Bernardino County Young Republicans early on, including $2,500 on December 30, 2004 and $5,000 on June 8, 2005. In the case of the money that went from the Colonies Partners to SEBA and then from SEBA to the San Bernardino County Young Republicans, Biane was doubly insulated from being linked to Burum. In the case of the donations from the Colonies Partners to the San Bernardino County Young Republicans, there was just one layer of insulation between Burum and Biane, Mandel suggested, as the San Bernardino County Young Republicans did not bear Biane’s name but had been founded by Biane’s chief of staff, Matt Brown, and another staff member, Tim Johnson. “This is all the secret money going back and forth,” Mandel said. “The San Bernardino County Young Republicans was set up for Paul Biane’s secret control. Matt Brown in his early conversations [with investigators] said that PAC was to support his [Biane’s] elections. Matt Brown and Tim Johnson were Biane’s staff members. It’s not small money. This money does mean something to them.”

Just as Burum employed Erwin and SEBA to conceal the secret flow of money to those he was seeking to influence, he used other PACs to funnel money to them and stay off the public radar, Mandel said.

The $100,000 given to Kirk’s Alliance for Ethical Government after the settlement was in place was not, Mandel said, the first example of Burum’s largesse to Kirk.

Some two years before Mark Kirk created the Alliance for Ethical Government, he had created another committee, the West Valley Young Republicans.

“In 2005, the West Valley Young Republicans got a $10,000 donation from the Colonies [Partners],” said Mandel. “This meant something. There was also the promise of more.”

Burum had purchased Kirk’s services with that money, Mandel suggested.

“Once [Ovitt was in office] he did not talk to Mr. Burum or Mr. Richards about the Colonies trial,” Mandel said. Thus, Kirk almost immediately upon coming into office was working as an intermediary between Burum and Ovitt, seeking to keep his boss committed to settling the Colonies litigation on terms favorable to Burum, according to Mandel. This was evidenced, Mandel said, by Kirk angling, very early on, to put himself into place to influence Ovitt with regard to the Colonies litigation. She displayed for both juries a December 7, 2004 email from Kirk to Ovitt, sent the week Ovitt began as supervisor, in which Kirk was pushing his boss to be allowed to participate in the closed sessions of the board of supervisors where ongoing litigation against the county and legal strategy with regard to it was routinely discussed. “Both Brad [Mitzelfelt, Postmus’ chief of staff] and I agree that if you want me in there [closed session meetings] for issues, then I should be there. Just because they haven’t done it [permitted chiefs of staff to participate in closed sessions in the past] isn’t a good enough reason,” that email stated.

Further indication that Kirk was doing Jeff Burum’s bidding consists of a conversation he had with then-county counsel Ron Reitz, the county’s highest ranking in-house attorney shortly after Ovitt had taken office, Mandel said. Kirk at that point was already pushing Reitz to let the board settle the case short of trial. Mandel reminded the juries of testimony to the effect that Kirk had told Reitz, “You can’t handle the Colonies case like a regular case. It is a political issue.”

In further asserting to the juries that Burum had unduly influenced the board to impose on the county a settlement lopsidedly in favor of the Colonies Partners, Mandel referenced a tentative ruling by the Fourth District Court of Appeal that was highly favorable to the county in the litigation with the Colonies Partners. That ruling reversed San Bernardino County Superior Court Judge Peter Norell’s ruling that the county had abandoned its flood easements on the Colonies Partners’ property. That ruling gravely undercut the Colonies Partners’ claim that the county had unjustifiably seized the Colonies Partners’ property, and the ruling brought into question the validity of the development company’s claim for monetary damages. Postmus and Biane had convinced the rest of the board to approve allowing the two of them, in the company of several of the county’s attorneys, to have “a small low key meeting” with Burum and the other managing principal in the Colonies Partners, Dan Richards, along with the Colonies Partners’ legal representatives, to discuss the implication of the appellate court ruling. Biane went into the meeting enthusiastically anticipating to confront Burum and Richards from the position of strength the county had just gained by virtue of the appellate court’s recent ruling that the easements remained intact and that the county potentially owed the Colonies Partners nothing, Mandel said. But in the course of that meeting, Postmus and Biane dismissed the attorneys from the room, leaving themselves in a negotiating session involving Burum and Richards, who were accompanied by their consultant, Jim Brulte, the then-recently termed-out state senator advising them on how to achieve a favorable resolution of the litigation. In that forum, a proposed $77.5 million settlement was arrived at which included a $22 million cash payout and the county turning over to the Colonies Partners property in Rancho Cucamonga deemed to be worth $55.5 million.

The fashion in which Biane bowed before the will of Burum and Richards in this instance, Mandel said, illustrated his first loyalty was not to the constituents who voted for him but the Colonies Partners, which was providing him with generous dollops of political cash.

Mandel said action that Biane engaged in with regard to expenditures from or use of the money in his own electioneering account – Paul Biane for Supervisor – demonstrated he knew in advance that both he and Postmus were going to receive money down the road from the Colonies Partners in return for their support of the lawsuit settlement.

In spring 2006, as Postmus was engaged in a challenge of then-incumbent assessor Don Williamson, Biane, who had $290,392.20 in his political war chest, loaned Postmus $100,000.

Mandel said Biane made the loan despite Postmus having at that time checked into drug rehab and then leaving before he had completed the program. “It was evident in 2006 he was clearly under the influence of some type of substance,” Mandel said. “Mr. Biane loaned him $100,000 because he knew Mr. Postmus was going to be able to pay it back.”

The investment of that kind of money inPostmus’ political future, given his proclivity toward drug use, would have been an unacceptably risky move by a serious politician such as Biane, said Mandel. This demonstrates Burum was indemnifying Postmus and Biane, she said. “There was no way Mr. Postmus was going to pay that money back if it backfired,” said Mandel. “There’s no other explanation why Mr. Biane would have loaned $100,000 to Mr. Postmus, who was spiraling out of control, unless he knows he’s going to get it back.”

The most damning testimony against the defendants in the trial came from Adam Aleman, whose version of events was more or less an encapsulation of the prosecution’s narrative and theory of guilt. In roughly descending levels of importance to the prosecution below Aleman was the testimony of Postmus, supervisor Josie Gonzales, Colonies Partners publicist Patrick O’Reilly, former county counsel Ron Reitz and former chief county administrative officer Mark Uffer.

By a substantial margin, the defense expended its greatest effort in attempting to impeach, discredit and demonize Aleman. In deference to that, Mandel acknowledged that Aleman stands convicted of four felonies, had been demonstrated as being dishonest and that his credibility on many points was subject to question. Nevertheless, she said, he had been intimately involved with the operation of Bill Postmus’ office during the time in question and he offered an important window on what had transpired. “Believe what is believable here, and you disregard the rest,” Mandel told the juries. “Every witness should be looked at closely. Look at the totality.”

She claimed Aleman’s testimony with regard to hit pieces targeting Biane which were used to coerce Biane had been corroborated by Patrick O’Reilly, Burum’s friend and public relations specialist who had no enmity toward Burum and Erwin. Aleman’s statements to investigators with regard to the PAC money that were in large measure an ignition point for the investigation that led to the prosecution of the case against Burum, Erwin, Biane and Kirk are corroborated by campaign finance documents, she said.

Further evidence of the conspiracy involving Burum, Postmus, Biane, Kirk and Erwin consists of the communication and coordination that went on between them while county officials and their attorneys were seeking to mediate a settlement with the Colonies Partners, Burum, Richards and their attorneys, Mandel said. She displayed phone bills and billing statements from the Colonies Partners’ publicist, Patrick O’Reilly, showing Postmus and, to a slightly lesser extent, Biane were meeting with or speaking by phone with Burum, Erwin and the Colonies Partner’s public relations team. Those contacts, she showed, included O’Reilly assisting Postmus and Biane drafting public and statements that advanced the idea that a settlement of the lawsuit was in the county’s interest.

Moreover, she said, there was evidence suggesting Postmus was outright militating on the Colonies Partners’ behalf and acting as their agent.

“Matt Brown testified Postmus would come out of closed sessions and tell Jim Erwin everything,” Mandel said.

Mandel noted that O’Reilly had been a powerful witness on behalf of the prosecution and that the damage he inflicted on the defendants, in particular Burum, went uncontroverted by the defense.

“Mr. O’Reilly wasn’t asked a single question” on direct examination by the attorneys for all four defendants, she noted. She reminded the juries that on the witness stand O’Reilly testified “Mr. Burum told me large amounts of money would be given to candidates he favored.”

This established an important element of the crime, Mandel said. The perpetrators of the criminal acts had moved forward in stages, Mandel said, in a carefully choreographed fashion that masked there was a quid pro quo at play. “The care that Mr. Burum took to structure the deal is evident,” she said. Burum did not pay the bribes, which were disguised as donations to the PACs, up front, Mandel said, but waited until after the settlement was made. That did not magically transform those kickbacks into non-bribes, Mandel said. “It’s not a defense to wait until after the settlement to pay the bribe,” she said.

And the explanation the defense offered that the payment of $100,000 to Postmus, who voted for the settlement, $100,000 to Biane, who voted for the settlement, and $100,000 to Kirk, whose boss, Gary Ovitt, voted for the settlement, were simply attempts to build bridges with county politicians in the aftermath of a hard fought legal battle as part of an effort to make sure that the Colonies Partners would be able to work on a cordial basis with the county in the future did not stand to reason, Mandel said. Those the Colonies Partners had to build bridges to at that point were the two members of the board, Josie Gonzales and Dennis Hansberger, who had opposed the settlement, Mandel pointed out. Indeed, after the settlement, Burum provided $200,000 that was used in Neil Derry’s 2008 campaign to defeat Hansberger when he ran for reelection. In this way, the two separate $50,000 donations to the PACs Postmus controlled, the $100,000 donation to the PAC Biane controlled and the $100,000 donation to the PAC Kirk controlled came across as rewards for the three votes to approve the settlement – quid pro quos, Mandel said.

The conspiracy was a grand one, Mandel said, consisting of many independently moving parts, all of which when isolated did not rise to the level of a criminal act. But in cohesion and in causation and ultimate result, they coalesced into felonies and a $102 million larceny, she maintained.

“In and of themselves, these acts are not illegal,” Mandel said. “In the totality of the evidence, they clearly are. The line is crossed when the elements of each of these crimes have been proved.”

In her final summation and penultimate appeal to the jurors before the commencement of the defense attorneys’ final arguments, Mandel said, “Your job is to keep an eye on the ball and not be distracted by smoke and mirrors. The question in all this is, ‘Was that settlement good for the county?’ Ladies and gentlemen, there is a line, and that line was crossed here. This was an obscene abuse of the public trust. This was a group of men who thought they could to anything. It is time to hold them accountable for their crimes.”

In the trial, from January until June, the prosecution put on its case, calling 34 witnesses. After the July 4 break, the defense teams for all four defendants responded by not calling any witnesses and resting after less than a half day’s presentation of stipulations, a series of facts or sworn statements which both the prosecution and defense concede are accurate. The tacit statement in the collective defense’s decision not to call witnesses is to imply that the prosecution had failed to establish its case.

In this way, the defenses’ closing arguments, which began on Wednesday after Mandel concluded hers, represent, along with the cross examinations of the various witnesses throughout the trial, gravitas of the defense case.

On Wednesday, Kirk’s attorney, Pete Scalisi, was the first of the defense attorneys to present a closing statement.

After thanking members of both juries – the one hearing the case against his client along with Burum and Biane as well as the other jury deciding Erwin’s fate – for their attention to the proceedings and for exhibiting tremendous patience throughout the trial, Scalisi told them the law dictates that they view the matter through a lens of presumptive innocence by which the prosecution has the burden of convincing them of guilt. He said the prosecution had not met that burden and that Mandel and her colleague Cope had been on a treadmill to nowhere from day one. “There’s reasonable doubt all throughout this case,” he said. “The way this evidence played out, none of our clients did anything wrong. None of them are guilty of anything.”

Scalisi rather daringly predicted both juries would return not-guilty verdicts before moving on to say that in the case of his client, Kirk could be acquitted on the basis of character witness testimony from three individuals Scalisi characterized as upstanding citizens – Ovitt, current county supervisor Curt Hagman and Biane’s former staff member Tim Johnson. All three vouched for Kirk’s character during the trial.

Of those, the one whose testimony was most germane to the charges against Kirk was Ovitt.

“Mr. Ovitt completely destroys the government’s theory,” Scalisi said. “Back in January, the government told you that Mark Kirk improperly, criminally, wrongly, influenced Gary Ovitt.”

Scalisi quoted Ovitt’s testimony during the trial. “He [Kirk] did not try to unduly influence me on any of the decisions I made,” Scalisi quoted Ovitt, continuing “It [approving the settlement with the Colonies Partners] was my decision, my decision alone. I stand accountable for it, not him [i.e., Kirk].”

The interpretation of this, Scalisi said, as pertains to Kirk is “case over. Mr. Kirk is innocent. He never unduly influenced Gary Ovitt. It is ridiculous to say ‘I can deliver Gary Ovitt’s vote when the entire world knew Gary Ovitt was going to vote in favor of the settlement before he came into office.”

Scalisi said “The very idea that he [Kirk] could bamboozle Jeff Burum by telling him he was going to deliver his [Ovitt’s]vote is ridiculous. Mark Kirk was just doing the things he was supposed to do. That’s why Gary hired him.”

The prosecution’s allegation that the defendants in general and Kirk in particular were hiding the $100,000 donations missed the mark entirely, Scalisi said. The donations were disclosed on all of the required reporting documents and Kirk had been the prime mover behind the county intensifying the disclosure requirements, which entailed putting the information on the county’s website.

A character witness for Kirk came from an entirely unexpected source, said Scalisi.

“Bill Postmus was a rising star in politics who was trying to hide his sexuality, trying to hide his meth addiction,” said Scalisi. “He didn’t say anything bad or negative about Mark Kirk.”

The $100,000 provided to the Alliance for Ethical Government by Burum was an entirely legal donation, Scalisi insisted. And the $20,000 from that PAC that Kirk paid himself which the prosecution said proves the donation was intended as a bribe was entirely legitimate as well, Scalisi said.

“Mr. Kirk got withdrawals for lawful consulting contracts,” Scalisi said, calling suggestions that was illegal “nonsense.” He said the prosecution’s own witness, former California Fair Political Practices division chief Lynda Cassady made a determination Kirk paying himself the consulting fee from his own PAC “was fully legal.”

Suggesting that Kirk was some kind of go-between linking Ovitt with Burum was a canard, Scalisi said, pointing out that Burum’s wife had been one of Ovitt’s students at Chaffey High School when Ovitt was a teacher there, and Ovitt had known Burum long before Kirk went to work for Ovitt.

“These are innocent men,” Scalisi said of all four defendants. “The prosecution says there is a conspiracy here. What conspiracy?There’s no conspiracy. It’s ridiculous. It’s an easy word to throw around. Once you start throwing it around, you better have proof. They’ve got nothing.”

Adam Aleman, upon whose information and testimony Scalisi said the prosecution had based its case, told the prosecution whatever it wanted to hear, “not even caring about what the truth is. The best that the government gives you is Adam Aleman?” Aleman’s misrepresentations to the investigators escalated into perjury before the grand jury and then when he was on the witness stand in the trial, Scalisi said. “He came into this courtroom, raised his right hand and lied. He was making stuff up as he went along.” He called Aleman’s testimony “a fairy tale.”

Prosecutors were colluding with Aleman, agreeing to reduce the felony charges he has pleaded guilty to down to misdemeanors in exchange for his perjured testimony, Scalisi said

“He’s going to walk,” Scalisi said.

Mark McDonald, Biane’s lawyer, accused the prosecution of engaging in “misrepresentation, taking a fictional stroll down conspiracy lane, using speculation presented as fact to make outlandish claims offered without proof. What I saw over the course of Tuesday and into Wednesday [when Mandel was offering her closing statement] was a piecing together of unrelated emails, messages and phone calls.” Mandel had not given them the truth, McDonald told the juries, but “presented to you a story she created.”

McDonald said the juries should not buy into Mandel’s creative assembly of exhibits and evidence after the fact. “What I urge you not to do is play with [the exhibits] and put them in an order that builds a case for guilt,” McDonald said. “These exhibits don’t prove anything.”

The prosecution had constructed its false story, McDonald said, on the basis of those misleading exhibits and the perjury provided by Aleman, whom he called “a mealy mouthed little liar. It was hard to look at him during trial, to see [him] go at it and at it. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything that blatant.”

He quibbled with the prosecution charging his client with both Penal Code 165 and Penal Code 86 violations. McDonald once specialized in prosecuting white collar and political corruption cases when he was with the Riverside County District Attorney’s Office.

“I have never been able to understand why there are two different parts of the law to cover the same thing,” McDonald said. He further said that the conflict of interest charge filed against Biane was misapplied in that Biane had no direct stake in the outcome of the vote.

He said the donations to politicians by developers or others having a stake in the outcome of a vote, even in close temporal proximity is not illegal.

A donor, he said, is “able to make those kind of donations. It might look bad. It might be distasteful. But the Supreme Court has said a political contribution made close in time to a vote is [Constitutionally protected free speech].” McDonald said basing a case on the fact that a politician had voted on an issue impacting a political donor was “a misunderstanding of the law. That’s why these guys are here.”

An indication the prosecution had taken evidence out of context to assemble “a false story” consisted, McDonald said, in the consideration that investigators for the district attorney’s office had induced Biane’s chief of staff, Matt Brown, to use an audio recording device to capture something on the order of 70 conversations he had with Biane in an effort to capture an utterance from Biane implicating himself. “I don’t know how many hours there were,” said McDonald. “It seemed like a lot.” Biane and Brown were close political affiliates, friends and mutual confidants, McDonald pointed out. “If Paul was going to tell anybody, it would have been Matt Brown,” McDonald said. Biane made no mention of bribery, McDonald said.

“This is a case that should never have been brought to trial,” McDonald said.

Saying he was reluctant to make such a recommendation, McDonald urged the juries to make a finding of not guilty “to send a message,” telling prosecutors, “‘You should not go after anybody who didn’t do anything.’”

Erwin’s attorney, Rajan Maline, began but did not finish his final argument on Thursday, after McDonald had concluded.

On the courtroom’s overhead visual projectors Maline displayed the text, “No one has ever been charged with this crime, aiding and abetting the receipt of a bribe.”

Mandel objected to the display. Judge Smith overruled it.

Charging his client with aiding and abetting, and by extension charging Burum with aiding and abetting, was a legal fallacy, Maline asserted. Someone who aids and abets a perpetrator in the commission of a crime must share the perpetrator’s intent, Maline asserted.

“The problem is they [Erwin and Postmus; and Erwin and Biane] don’t share the same intent,” Maline said. “To be an aider and abetter you have to have the same intent. Mr. Erwin can never be guilty of this crime.”

A hole in the prosecution’s case, Maline indicated, is that a key element of it is based upon Aleman’s contention that Erwin showed him fliers threatening to expose Postmus’ homosexuality and drug use and Biane’s dire financial circumstance.

But Aleman had been outfitted by investigators with, Maline said, “recording apparatus from December 18, 2008 until February 16, 2011.” Maline said that in none of the conversations Aleman recorded with Postmus did Aleman ask about the fliers or discuss with Postmus the six to 12 meetings between Postmus and Burum between January and June 2006 where Aleman claimed he was also present and where Aleman claimed the bribe to be paid in exchange for a vote in support of the settlement was discussed. Both of those failures to corroborate Aleman’s claims provide the jurors, Maline said, “a path to check the not guilty box on the verdict forms.”

Postmus testified, Maline said that “Burum never crossed the line” with regard to offering money in exchange for a vote. “And he told you the same thing when he got on the stand,” Maline said.

Prosecutors did not have sufficient evidence upon which to convict the defendants or to even bring charges, Maline said. “They doubled down on Aleman,” he said. “They had nothing else.”

The Colonies Partners had aggressively lobbied members of the board of supervisors to bring an end to the litigation, Maline acknowledged, but he said doing that was not illegal and was necessitated by the consideration that “The county was not negotiating in good faith.”

Maline ridiculed the prosecution’s claim that the political action committees controlled by the defendants were “sham PACS, [set up] in the dark of night. She [Mandel described them as sham PACS.” Those were genuine PACs, Maline said, and if they were sham PACs the prosecution would have the evidence to prove it, he said. “They [the prosecution] have every document these gentlemen own [as the result of having seized materials from the defendants’ homes and offices during searches pursuant to search warrants.] They’ve gone through everything with a fine tooth comb.” Maline dismissed the idea that “Mr. Erwin’s PAC is a secret. He filled out his [disclosure documents]. If anyone wants to go online, they’re going to know exactly who started it.”

Maline will finish his closing statement on Monday. He is to be followed by Stephen Larson, Burum’s lead defense attorney, a former federal judge. Mandel is permitted to make a rebuttal after the defense attorneys complete their final arguments. Thereafter, the juries are to begin their deliberations.

One jury is to return verdicts for or against Burum, Biane and Kirk. The other jury, deliberating separately, will decide Erwin’s fate.

Legitimate Criminal Enforcement New Vagrancy Control Tool

While issues with the homeless are seemingly universal in Southern California, the problem is more acute in certain areas.

Every January for the last several years, the county government and each of the 24 municipalities in San Bernardino County collaborate on what is called the “point in time count,” which tallies the number of homeless in the region. That count was carried out on January 26 of this year, finding 1,866 homeless people countywide, which was a slight reduction from the 1,887 counted on January 28, 2016. San Bernardino County compared favorably to most of the surrounding counties in terms of the ratio of officially counted homeless numbers to total population. In descending order, the cities in San Bernardino County with the highest homeless populations were: San Bernardino: 491; Redlands: 164; Victorville: 157; Upland: 127; Ontario: 91; Rialto: 91.

This drawdown in the number of the homeless clearly bucks the trend in Southern California. What at one time were referred to as vagrancy laws are no longer applicable following a legal development a generation ago. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville, struck down Jacksonville’s vagrancy ordinance, ruling unanimously that Florida city’s ordinance was unconstitutionally vague for failing to give a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice that “vagrancy” is forbidden while secondly it “encourage[d] arbitrary and erratic arrests and convictions.”

California, likely because of its hospitable climate for most of the year, hosts roughly one fifth of the homeless population in the United States. In the last 20 years, California cities, no longer able to rely on the state’s discarded vagrancy statute, have enacted a rash of laws which are essentially directed at people who are homeless. These restrict activities in a way calculated to encourage the dispossessed to leave. The ordinances criminalize activities that people without homes must undertake in public, such as sitting in public, loitering, begging and panhandling, or sharing food during daytime and camping in public and sleeping or lodging in vehicles at night.

While these ordinances have often had the intended immediate effect of driving the disenfranchised away, these draconian means are not without some degree of legal risk.

In 2006, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in the case of Jones v. City of Los Angeles held that “the Eighth Amendment prohibits the city from punishing involuntary sitting, lying, or sleeping on public sidewalks that is an unavoidable consequence of being human and homeless without shelter in the City of Los Angeles.” In October 2007, the parties settled the case and sought withdrawal of the opinion, which the Court of Appeals granted. Nevertheless, the ruling in Jones v. City of Los Angeles set the prevailing standard which effectively prevents ordinances from criminalizing conduct that, due to the shortage of housing for the homeless, is an unavoidable outgrowth of being without a place to live, making it legally unacceptable for cities struggling with homeless population challenges from shifting the homeless from the streets to jails.

Again pushing the envelope of what restrictions could be placed on the homeless or what ordinances or policies could be employed to induce them to leave, the City of Los Angeles enacted an ordinance allowing authorities to seize and discard unattended personal property located on public property, in particular sidewalks. This provoked a lawsuit, Lavan vs. Los Angeles, in which eight homeless people claimed their personal belongings were illegally taken from the sidewalk when they got up to use the restroom or run an errand. In September 2012, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that the city was not allowed to remove and destroy unattended property on the sidewalk, citing Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment violations. The City of Los Angeles for two years sought to appeal the ruling and amend the consequent injunction it entailed, but the U.S. Supreme Court did not deign to review the ruling.

Throughout much of San Bernardino County, officials have taken a clever approach that reduces considerably the potential for legal liability. Rather than enforce those laws which could be construed as targeting the homeless, they have moved to a strategy of enforcing, where the behavior of the destitute population warrants such, other elements of the penal code against them. This enforcement is done in a high-profiled and conspicuous manner calculated to come to the attention of others living on the streets, sending an unmistakably clear message that they should think long and hard about remaining in place.

For their part, law enforcement officials maintain that they are merely enforcing the law. They say those homeless individuals arrested were rung up on crimes that would have triggered the arrest of anyone – homeless or housed – perpetrating them. And, they say, there is no greater premium on prosecuting the homeless than prosecuting anyone else.

It is worth noting, nonetheless, that several of the county’s law enforcement agencies make a point of publicizing the more sensational arrests of those they refer to as transients.

On Tuesday morning August 15, the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, which provides contract law enforcement services to the City of Chino Hills, arrested Edward Lopez, a transient, on suspicion of robbery, vandalism and attempted arson. Deputies maintain Lopez tried to use a lighter to ignite a fuel nozzle.

Deputies went to the gas station/Circle K, located at 4200 Chino Hills Parkway, following a report that a man was vandalizing the convenience store by breaking several glass shelves and that he took two refrigerated Coca-Cola coolers and then chased employees out of the store. Thereafter, according to the sheriff’s department, Lopez attempted to use a stolen cigarette lighter in an effort to ignite a fuel nozzle on one of the gas station’s fuel pumps. After Lopez fled into the Circle K and locked the door behind himself, he relented and let the deputies in, at which point he was taken into custody. According to deputies, Lopez had previously vandalized playground equipment at Chaparral Elementary School in Chino Hills on August 9 and had slept on the campus.

On Monday, August 14, 2917 at 11:08 p.m., San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies responded to a report of a break-in attempt at a business office in the 17100 block of D Street in Victorville. Deputies came upon a suspect, later identified as Marcus Joseph Dewitt, 28, nearby. Believing Dewitt had just left the business, they confronted him. The department says a deputy deployed a stun gun on a Dewitt, described as a transient, when Dewitt attempted to strike the deputy and refused to follow his verbal commands. Dewitt was taken into custody and booked into the Adelanto Detention Center in lieu of $50,000 bail on suspicion of resisting a police officer.

Christopher Barrios, identified as a 35-year old transient, was taken into custody August 11 at 8:34 a.m. in Victorville and charged with resisting and obstructing an officer. A confrontation between Barrios and sheriff’s deputies ensued after the deputies came to a home in the 15300 block of Center Street in response to a domestic disturbance call from Barrios’ estranged wife. According to the department, Barrios “became angry and argumentative with his wife [after] deputy D. Carpenter responded to the location and while talking to the involved parties. Due to the suspect’s erratic behavior, deputy Carpenter attempted to detain him, for the safety of all parties.” The department maintains Barrios fled and hid beneath a wooden container until he was found by deputy A. Pen. Barrios became combative when the deputies approached and pepper-sprayed him.

On August 14, officers with the San Bernardino Police Department arrested Renee Hernandez Jr., who was living in the vacant Happy Boy Car Wash in the 500 block of North Flores Street in San Bernardino. County fire fighters responded to that location at 3:05 p.m. that day in response to a report of a fire. Upon arrival, firefighters extinguished the blaze. Hernandez told firefighter he lit the fire. A San Bernardino County fire investigator questioned Hernandez, determining he had intentionally set the fire. Hernandez was transported by an officer with the San Bernardino Police Department to West Valley Detention Center where he was booked for arson, trespassing and a San Bernardino Municipal Code violation. His bail was set at $150,000.

In Redlands on August 11, Redlands police officers detained and then arrested Isaac Edward Allen, described as a 21-year-old transient from San Bernardino, near the underground parking structure at Citrus Avenue and Fifth Street. According to the department Allen had several items which they believe he had stolen when he had burglarized Citrus Valley High School sometime between the early afternoon of July 31 and mid-morning on August 1. It was subsequently determined that the items, which have not been described, were equipment the school owned. Allen was booked on suspicion of having stolen or having received stolen items. Allen had an outstanding warrant, Redlands Police said.

On August Friday 4, Redlands police arrested Julio Nestor Flores, 23, a transient, after he got into the back seat of a pregnant woman’s car. The woman, who was 8 months pregnant, was at the Shell gas station at 127 Redlands Blvd., according to the police “placing her 18-month-old baby in the back seat of her SUV when the subject opened the other rear door and sat next to the baby. The mother became frantic and fled the parking lot with her baby in her arms.”

Police said Flores sat in the vehicle for a brief period, but attempted “to walk away when officers arrived,” according to a police department web post. Flores had apparently sought to get into another vehicle earlier while he was in the Vons parking lot in the 500 block of Orange Street, but was thwarted when the driver pulled away. Flores, who was on probations, was arrested on suspicion of being under the influence of a controlled substance

On August 4 in Victorville, 28-year-old Dontra Anthony Morris, described as a transient, was arrested after attempting to break into multiple vehicles at Valley-Hi Toyota in the 14600 block of Valley Center Drive that morning. A dealership employee spotted Morris trying to get into vehicles in the service area. He was told to leave but a short time later he went into the parts department, according to the sheriff’s department, where he attempted to steal merchandise.

Dealership employees escorted Morris off the property prior to deputies arriving, but with assistance from California Highway Patrol’s Airship H80, sheriff’s service specialists G. Bracamontes and C. Rodriguez located him in a shopping center off Seventh Street, near La Paz Drive, the sheriff’s office said. Morris was observed attempting to enter a vehicle parked at the shopping center and was taken into custody. Morris is on probation for attempted grand theft and had been arrested on May 27 after trying to steal a vehicle from the garage of a home in Victorville. Morris was arrested on suspicion of attempted grand theft auto, attempted burglary and felony violation of probation and was booked at the High Desert Detention Center.

On August 4, 31-year-old Daniel Davila, a transient, was arrested in Victorville after he attempted to walk away from the Office Max office supply store at 12628 Amargosa Road with a printer he had not paid for. Davila pushed and hit employees who confronted him, according to the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department. The Office Max employees succeeded in taking the printer away from Davila, who fled, crossing the I-15. Davila was located by sheriff’s deputies and arrest. He was booked at High Desert Detention Center for robbery.

On Wednesday July 26, Danielle Alexandria Giangrossi, 32, a Victorville transient, was arrested on suspicion of arson after firefighters responded and doused a fire near the Rancho Seneca Apartments in the 14700 block of Seneca Road. Investigators concluded that Giangrossi set fire to a transient encampment near where she was living. She was arrested by the fire department and booked into the High Desert Detention Center in lieu of $50,000 bail.

Just before midnight Monday July 17, Jeremy Byrd, a 30-year-old transient, was arrested on suspicion of possession of a stolen vehicle and on a warrant for driving with a suspended driver’s license. Byrd and the vehicle, a 2003 Chevrolet Silverado, were spotted by sheriff’s deputy Jared Sacapano in line at a Del Taco drive-thru in the 12200 block of Apple Valley Road in Apple Valley. Sacapano checked the license plate of the pickup. It turned out to have been reported as stolen from Boron.

Clorinda Garcia, a 29-year-old transient, was arrested in Highland on July 6 and charged with stabbing her boyfriend with a pair of scissors. At 10:05 p.m. that evening, a man with a stab wound was found walking near Base Line and Sterling Avenue. Medical aid was summoned, and he was taken to the hospital. Investigating deputies learned he had been stabbed after an argument with his girlfriend, identified as Garcia. She was located at a nearby transient camp in Highland and booked into the Central Detention Center in San Bernardino on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon. Her bail was set at $50,000.

John Mosby, a 58-year-old transient was arrested July 3 after having allegedly shot a man the previous day in the area of Bear Valley Road and Second Avenue in Hesperia. Mosby was found and taken into custody near Main Street and Cataba Road by San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department deputies, who were assisted by the Specialized Enforcement Division. He was arrested and booked into the High Desert Detention Center on suspicion of attempted murder. Mosby is currently being held in lieu of $1 million bail and the motive for the shooting is under investigation.

Deputies with the Hesperia Sheriff’s Station were dispatched to the 16700 block of Bear Valley Road at 2:58 a.m. on Sunday July 2 after receiving a call of shots fired. Arriving deputies found a male victim suffering from a gunshot wound. He was transported to a trauma center. Mosby fled the scene before deputies arrived, but was ascertained to be a suspect in the shooting.

On Wednesday June 1, two transients believed to have been living at a homeless encampment in Victorville were arrested following a traffic stop in Loma Linda, after deputies discovered a significant amount of stolen personal property within the vehicle in which they were riding.

When Steven Vigil, 40, and Desiree Rodriguez, 35, were subjected to a vehicle check on California Street conducted by Loma Linda deputies B. Ortiz and L. Sandoval along with Sgt. A. Garcia, Vigil was determined to be a parolee at large with an active no bail warrant and Rodriguez was found to have several arrest warrants. A search of their vehicle found they were in possession of a “significant amount of other persons credit cards, ID cards and social security cards,” according to the sheriff’s department. Ortiz contacted several victims and it was determined they obtained the property during two burglaries.

Vigil was arrested and booked him into the Central Detention Center without bail. Rodriguez’s matter has been referred to the district attorney’s office.

Geraldo Gonzalez, a transient, was arrested twice, once when he broke into a child care center in Redlands on May 22 and again on May 27, when he sought to enter that city’s federal building from the roof where he left a water valve running.

On May 22, Gonzales got into the Redlands Day Nursery at 1643 Plum Lane by defeating a locked door. He was arrested after the alarm system summoned a nursery employee and the police. He was booked but released on May 24. On May 27, Gonzalez scaled to the top of the U.S. Geological Survey Building at 1653 Plum Lane, where he opened a water valve. He was found in a field next to the building after federal police were summoned. Those federal officers took him into custody and he was charged with trespassing on federal property.

Vontrell Lamarr Wynn, a transient from Victorville, was arrested on May 25 after he robbed the In-N-Out hamburger stand at 15290 Civic Drive in Victorville at gunpoint. Deputies from the Victorville sheriff’s station were summoned shortly after the incident, and employees gave a description of the suspect, later identified as Wynn. Deputies searched the area and located Wynn behind the Food 4 Less on La Paz Drive. Wynn was positively identified by the employees as the suspect who robbed the business. Wynn was booked at the High Desert Detention Center on suspicion of robbery and is being held in lieu of $125,000 bail.

Ruben Guzman, a transient man from the Redlands area was arrested Tuesday, May 23, and charged with breaking into an elderly woman’s home in Mentone, where he allegedly attempted to sexually assault her.

Guzman, 31, was found in the area shortly after the incident was reported. He was arrested and booked into jail on suspicion of burglary, elder abuse, attempted rape, and assault during rape.

The woman, identified as more than 65 years of age, told deputies a man she did not know forced his way into her home, “physically assaulted and attempted to sexually assault her,” according to the sheriff’s department. When he fled, Guzman took the woman’s phone, the sheriff’s department said. “Evidence of the crime linking the suspect to the incident was located,” according to a sheriff’s department release.

Adrian Tostado, a 30-year-old transient was arrested on Tuesday, May 23, for having intentionally lit trash cans on fire at a park in Highland. Images of Tostado captured by a videocamera show him walking near two trash cans on fire at Highland Community Park at 7793 Central Ave. at around 5 a.m., according to the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, which provides contract law enforcement service for Highland. Tostado “made no attempt to extinguish the fire or call for assistance,” the sheriff’s department maintains. He was found roughly a block away, near another trash bin that was on fire, the sheriff’s department claims.

Tostado was arrested on suspicion of arson and booked into jail with bail set at $50,000. -Mark Gutglueck

Terminated Whistleblowing Fontana Police Officer Seeking Reinstatement Tuesday

By Carlos Avalos

Next Tuesday, August 22, 2017, David Moore, who had worked the last 16 years of his 23 years in law enforcement with the Fontana Police Department, will fight to be fully reinstated in his job as a police officer together with recovering five months of back pay when he comes before the Fontana City Council for a hearing.

Moore was ignominiously fired from the Fontana Police Department in March. That firing has a significant backstory, indeed a backstory with several layers.

The justification the department gave for cashiering Moore had nothing to do with using excessive force, nor pilfering items out of the department’s evidence locker, nor was he suspected or proven to have framed civilians with crimes they did not commit in the course of his work in the field or while he was carrying out investigations. And he was not charged with falsifying a police report. Indeed, Moore’s firing had nothing at all to do with his comportment on the job. Rather, his badge and service gun were taken from him because his wife, now his ex-wife, was listed as a beneficiary on the health insurance policy Moore was entitled to as one of his employment benefits. He had, the department maintained, phoneyed up a document pertaining to his health benefits policy. When the department’s internal affairs division came across this circumstance, he was placed on administrative leave, pending an investigation. It was not the first time he had been put on administrative leave.

During the investigation, Moore maintained his innocence and judicial records show that he marshaled proof in the form of a court order from a family law court judge that his wife remain as a beneficiary on his health plan until his divorce was finalized. Moore also produced a letter from his divorce attorney, which explained that he was acting on the advice provided by his divorce attorney. Despite his provision of those exhibits, Moore was terminated.

In effort to inflict more punishment on Moore, the Fontana Police Department denied unemployment insurance to him, contending that he intentionally committed fraud. Moore took the matter before an Unemployment Appeals Court. Two weeks ago, administrative law judge Catherine Leslie ruled in Moore’s favor with regard to his appeal for unemployment income. Records from that appeal stipulate that, “There was insufficient basis to establish that Moore willfully and intentionally breached his duty to his employer.” Next week, the Fontana City Council, sitting as the city’s de facto civil service commission will hear a fuller range of arguments as to whether Moore should be reinstated, including being reinstated with back pay.

The general contention is that the issue relating to keeping his wife on his health benefit account was merely a pretext, and a pretty poorly constructed one at that, to fire him.

Moore’s actual transgression had nothing to do with falsifying his benefits application and everything to do with his recurrent role as a whistleblower within the department.

A whistleblower is defined as a person who exposes any kind of information or activity that is deemed illegal or unethical. For the most part, whistleblowers are members within an organization rather than outsiders. While there are whistleblowers in both the corporate world and the public sector, the classic examples of whistleblowers are those within the public sector, generally government employees. Their positions and the authority they wield – limited or extended – vantages them to not only observe government and governmental operatives in action but endows them with a specialized knowledge of how government works, what the standard procedures are, how records and documentation are kept, what the political and bureaucratic lay of the land is. In short, they are insiders to some degree or another and they possess the knowhow, the data, the credibility and, most importantly the access to information, that allows them to reveal to the world, or at least a part of it, what is actually going on or what has gone on in the day-to-day function of that particular organization.

Some whistleblowers have purer motives than others. Some come forward out of conscience and something akin to altruism – a sincere desire to do what is right and make sure that others with power do not misuse that power. Others are whistleblowers because they themselves have been less than exemplary in their own behavior and action and use of authority and they have now been caught themselves or are on the brink of being caught and it now behooves them in some way to provide a wider context to the atmosphere in which their own misdeeds took place.

Whatever their motivation, whistleblowers are generally not in favor with their masters – their political masters or their professional masters or their employers. By whistleblowing, they are bringing attention to issues and behaviors those with authority beyond their own would rather remain below deck, off the radar screens, outside the consciousness of the public at large. With exposure of things that are not quite right comes demands for accountability and reform. Those holding the power and authority are not without recourse; they can bring that power and authority to bear. Those doing the whistleblowing almost always fall under the authority, within the purview or inside the bureaucratic reach of those being exposed, and those exposed are quite often at liberty to vector their power and bureaucratic control on those individuals who have exposed and embarrassed them. Bureaucratic infighting often takes the form of discrediting the whistleblower, subjecting him or her to exposure as well, and applying discipline or the force of law.

The most celebrated whistleblower within the last several years was Edward Snowden, the one-time Central Intelligence Agency employee who had become a contractor with the National Security Agency. In his role, Snowden learned that the government was overstepping its legal authority and violating – wholesale – Americans’ constitutional rights. He abided it for a time, but upon hearing the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, lie under oath to Congress on March 12, 2013 by denying the existence of the metadata collection systems Snowden knew existed, he took it upon himself to reveal, in a profound example of whistleblowing, the existence of those systems to the New York Times, the British newspaper the Guardian and to documentary maker Laura Poitras.

Snowden explained himself and the motives behind his actions, saying that when a person in the position of privileged access is exposed to much more information on a broader scale than the average employee, two of several things can happen. One of those is that the individual becomes inured of what he sees and knows and begins to consider it routine, justifiable and acceptable. The other reaction – one that is a common theme with whistleblowers – is to become disturbed and outraged. Such a reaction carries with it danger and life- or career- threatening implication. And it can bring the full force and authority of the government – the larger government and not just that branch of it about which the whistleblowing was done – down on the head of the whistleblower. In Snowden’s case, his whistleblowing touched on the National Security Agency. And, to be sure, the National Security Agency used its power and authority against Snowden, using its ability to monitor – whenever and wherever it was not thwarted by Snowden’s countermeasures – his every effort at communication through whatever means and to track his moves and whereabouts. But the NSA did not stop there. It networked with other branches of the U.S. Government to bring him to heel. The U.S. Department of Justice in secret lodged charges against him, unsealing them on June 21, 2013, at which point it was revealed he had been charged with two counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and further counts pertaining to the theft of government property. The U.S. Customs Agency revoked his passport. He transited to Hong Kong and hence on to Moscow, where Russia granted him asylum, and where he yet resides, while the U.S. Government remains intent on prosecuting him if he can ever be brought back. As for those whose violation of the law – such as Clapper who oversaw the illegal surveillance and then perjured himself before Congress – drove Snowden to become a whistleblower, the U.S. Government has given them a pass and they have gone uncharged, unindicted and unpunished.

So it was with Officer David Moore. He had been an exemplary officer with the Fontana Police Department. As an African-American on a police force whose members are overwhelmingly white, he worked hard to fit in within the Fontana Police Department after he took a lateral transfer from the Los Angeles Police Department in 2000.

Moore’s fate, at least as far as within the context of the Fontana Police Department, has become inextricably linked with that of a Hispanic officer with the department, Andrew Anderson, who has been with the department since 2002. Anderson too had begun his career with the LAPD.

Moore and Anderson are known for speaking out about what they perceive as unfair practices where they are employed. Not only were Moore and Anderson sensitive to the racial disparity within the department, they voiced their concerns about what they say is inadequate leadership within the organization. Moore often decried the cliques and subculture within the department, pointing out that certain individuals, usually Caucasian SWAT [special weapons and assault team] officers, were swiftly promoted. Moore also spoke openly about the convoluted promotional process, which requires candidates to privately campaign for positions within the department. This arbitrary promotional process allowed the administration to handpick those individuals who they felt “fit the overall goals of the department.”

Despite his outspokenness, Moore was for many years given glowing performance reviews. That has changed within the last few years, shortly after Moore eclipsed his 22nd year in law enforcement. The first incident occurred in November 2015, when Moore and Anderson, who lived in the same neighborhood in Hesperia, decided to check on the health and wellbeing of their elderly neighbor, Steve Olsen.

Two squatters had covertly moved into the elderly man’s house. Without paying rent, they assumed control over the elderly man and his home. They forced Olsen to live as a recluse inside of his own garage. Anderson and Moore reported the incidents of abuse to their department; however the matter was never investigated. The elderly gentleman would show up to gatherings with evidence of physical abuse about his face and body.

One night, after hearing sounds of distress coming from Olsen’s garage, Moore and Anderson, both police department supervisors at the time, did a welfare check on their neighbor. Once Moore and Anderson came onto Olsen’s property, one of the male squatters attempted to access a knife. Moore and Anderson restrained him.

Olsen was found unconscious inside his garage, slumped over the steering wheel of his car. The sheriff’s department, which provides law enforcement service to the City of Hesperia under a contract, was called. The responding officers addressed the matter, and cleared Moore and Anderson of any wrongdoing.

Olsen survived this incident, but would not be so fortunate in the months to come.

Moore and Anderson reported the incident as proscribed by their department policy, and solemnly warned the Fontana Police Department that if law enforcement did not intervene in the odd living arrangements at Mr. Olsen’s home, he would very likely soon be dead. Anderson and Moore’s assessment of the situation was disregarded by their supervisors with the Fontana Police Department, and those higher-ups decided against making an agency-to-agency request to the sheriff’s department to look into Olsen’s circumstance to ensure his welfare. Eleven months later, Steve Olsen died in the care of the two squatters.

The male squatter who was detained by Anderson and Moore complained to their employing agency, the Fontana Police Department. To Moore’s and Anderson’s mortification, the Fontana Police Department, without regard to the determination made by the sheriff’s department with regard to the initial call regarding their confrontation with the squatters, initiated an internal department investigation of their action. The Fontana Police Department relieved Anderson and Moore of duty and declared their conduct unbecoming to the department.

The Fontana Police Department suspiciously lost some of the initial recordings of the calls from Moore and the squatters. A memorandum was completed by a lieutenant, which was supposed to contain Moore’s verbal report of the incident. This memo was forwarded up the chain of command. The memorandum was filled with false statements and allegations which conveyed Moore and Anderson were not truthful and honest in their reporting. The recording which contained Moore’s actual verbal report of the incident was somehow lost. Under the direction of former Chief Rodney Jones, Moore and Anderson were accused of false and misleading statements. They were terminated and compelled to participate in an administrative hearing to keep from having their careers ruined.

During the hearing it was established that Moore and Anderson had been truthful. They produced their audio recording of what Moore actually reported the night of the incident to the lieutenant, to prove that their statements in fact were accurate. The audio recording and other evidence marshaled by them cleared them of lying. It further brought into question the integrity of the internal investigation process and the action of the chief.

As a result of this investigation, the officers were reinstated to full duty. In a face-saving gesture for the department, Fontana City Manager Ken Hunt gave them 30-day suspensions without pay. Moore and Anderson would not accept that punishment, asserting they had done nothing wrong in looking after their elderly neighbor and that there was no proof they had physically harmed the complainant. Anderson and Moore appealed the 30-day suspensions through an arbitration hearing.

During this hearing the city attorney accused Moore and Anderson of conduct unbecoming. After a short opening statement by Moore’s attorney, the city attorney asked for a brief intermission. The city attorney approached Moore with a settlement offer. The offer was to reimburse Moore of his lost wages from the 30 days suspension and accept a letter of reprimand, which would be eliminated within one year’s time frame. Attorneys for Moore stated he was close to accepting the offer however, in fine print he realized the city was asking to be excused universally from liability. More rejected the offer and decided to file a civil suit to clear his name and reputation.

In early 2016, Moore and Anderson fought back, filing suit against the department. Officer Moore was dealing with this lawsuit and still working at the department as a police corporal, an unenviable position to be in. According to sources within the department, Moore was hated by some of his peers, and he was encouraged by others. In the same time frame, his marriage was in the course of dissolving.

In the early months of 2017, officer Moore was put on administrative leave by Jones’ replacement as chief of police, Robert Ramsey. For the second time within two years officer Moore was fighting for professional survival, up against the police department he had spent more than two-thirds of his career with. Both the Chief of Police Robert Ramsey and City Manager Ken Hunt terminated Moore.

Since his termination, now five-month ago, Moore has done all he can to make ends meet. Fontana city officials have not just snatched away his livelihood they also deprived Moore and his family of health benefits.

Moore’s experience with the Fontana Police Department has not been unique.

Dave Ibarra, a two-time Iraq War veteran, worked at the Fontana Police department for ten years, from 1996 until 2006. While at the Fontana Police Department, Ibarra received many commendations for his actions while in the line of duty. While at the Fontana Police Department, Ibarra noticed a core difference within the police culture, whereby high ranking officers in the department favored, with very few exceptions, certain Caucasian members of the department. Those so favored were known as the, “Golden Boyz.” These well-connected Golden Boyz swiftly advanced within the organization. African American officers were not permitted within this inner circle. Anyone who opposed their accelerated career advancements, according to Ibarra, became a target of the department’s administration. When it came to promotions, the rest of the members in the department found themselves scratching the bottom of the barrel, looking for any leftovers the chosen ones bestowed upon them. The Golden Boyz were hand-selected in advance by the administration, the members of which were previously selected by those elite members who came before them. This resembled a fraternity or secret organization.

Some have noted the similarity between the eagle depicted on the Fontana Police Department patch above and the eagle on the Nazi military patch shown below.

Dave Ibarra during his tenure at the Fontana Police Department experienced harassment from his white colleagues. Ibarra on numerous occasions made formal complaints about his mistreatment. Ibarra claimed that on numerous occasions he encountered odd behavior on the part of his white colleagues. He maintains he came across Nazi literature and high ranking officers giving the Nazi salute. Ibarra at one point stayed within the chain of command in reporting these anomalies, calling out the “Good ol’ Boy System,” or “Golden Boyz,” and openly challenging his superiors. Eventually he became more vocal about the lack of diversity at the top of the department and with regard to the different treatment Fontana officers afforded the white citizens of Fontana as opposed to the minority residents of Fontana. Those reports did not result in the reforms Ibarra thought necessary, and in 2006 he submitted his formal resignation and moved on to a different department. At that time, some of the opposing Fontana administrators asserted that Ibarra was a lone, disgruntled employee. Ibarra’s contentions were borne out, however, by at least a half dozen officers who provided similar accounts or complaints of police brutality, racism, hostile work environment, favoritism and racial disparity within the ranks. Some of these officers were Chris Burns, Paul Martin, Ray Schneiders, Cliff Ohler, Kurtis Slotterbeck. and recently David Moore and Andrew Anderson. Most of these so called disgruntled officers were forced to resign or medically retire. Andrew Anderson was recently forced to retire after he testified against the department during depositions.

Dave Ibarra during his tenure at the Fontana Police Department experienced harassment from his white colleagues. Ibarra on numerous occasions made formal complaints about his mistreatment. Ibarra claimed that on numerous occasions he encountered odd behavior on the part of his white colleagues. He maintains he came across Nazi literature and high ranking officers giving the Nazi salute. Ibarra at one point stayed within the chain of command in reporting these anomalies, calling out the “Good ol’ Boy System,” or “Golden Boyz,” and openly challenging his superiors. Eventually he became more vocal about the lack of diversity at the top of the department and with regard to the different treatment Fontana officers afforded the white citizens of Fontana as opposed to the minority residents of Fontana. Those reports did not result in the reforms Ibarra thought necessary, and in 2006 he submitted his formal resignation and moved on to a different department. At that time, some of the opposing Fontana administrators asserted that Ibarra was a lone, disgruntled employee. Ibarra’s contentions were borne out, however, by at least a half dozen officers who provided similar accounts or complaints of police brutality, racism, hostile work environment, favoritism and racial disparity within the ranks. Some of these officers were Chris Burns, Paul Martin, Ray Schneiders, Cliff Ohler, Kurtis Slotterbeck. and recently David Moore and Andrew Anderson. Most of these so called disgruntled officers were forced to resign or medically retire. Andrew Anderson was recently forced to retire after he testified against the department during depositions.

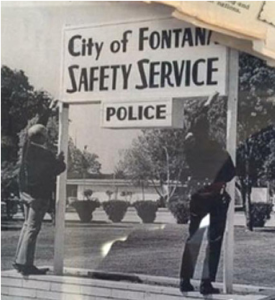

The Fontana Police Department for a time referred to itself as the safety service, or SS for short. Note the Teutonic Rune font used on the printing of the sign.

At one point, the Fontana Police Department renamed itself the Safety Service or the “SS.” Older officers and residents of the city say they remember during that time double lightning bolts could be seen on officers’ lapels, not unlike the lapel symbols of the Schutzstaffel of Nazi Germany, the SS, literally the “protection squadron.” In the 1950s Fontana police officers wore white uniforms. Older officers joked that the reason the uniform was white was so when officers got off of work they could take off their hats and put on their hoods. One of the police chiefs during this era was Ed Stout. Stout had been seen with a swastika tattooed on his arm and double lightning bolts on his back. Stout was known to have attended KKK meetings during his off-duty hours.

According to current and retired Fontana P.D officers certain images have been strategically and inconspicuously embedded within the culture of the Fontana Police Department, some of which are in plain sight; others are concealed on the bodies of officers in the form of tattoos, like badges of honor. The Fontana Police Department has a SWAT logo which takes as its primary element an eagle. To the casual observer, it might simply be an American bald eagle, a standard American symbol. This eagle does not look away way like the US Eagle. A closer look reveals that it more closely resembles the symbol of the Nazi Party, which has been adopted as emblem of many white supremacy groups. A small diamond is placed dead center on the Fontana Police Department’s winged SWAT logo. Several outlaw motor cycle gangs, as well as Nazi and white supremacy groups, use the diamond to symbolize the one percenters, or the small elite group of hardened soldiers who were selected to carry out key, specialized and dangerous assaults on specific targets.

In the Fontana police chief’s office there is a statue of a large owl with Germanic code beneath the logo. This same owl is visible on the patch worn on the arm of the rapid response team uniform, a unit founded by former chief of police Rodney Jones. On that patch, just below the owl there is Germanic Rune writing, which spells out RRT. All of this is a subtext, of course, and it is unclear, precisely, whether this symbolism is merely a paramilitary conceit or whether it signals, in a code to the initiated, a suggestion relating to white supremacy. We must remember, White supremacy groups cherish and admire the same Nazi paraphernalia, but they are extremely careful not to plagiarize fellow organizations.

Currently, Hispanics comprise roughly 69 percent of Fontana’s 212,000 residents. African-Americans comprise slightly more than ten percent of the city’s population. Nevertheless, the 194-member Fontana Police Department is composed of sworn officers who are predominantly white, such that it has never had more than four African American officers on the force at any given time. The department employs fewer than thirty Latino officers – roughly 15 percent of the force. The department’s prestigious special enforcement detail (SED), the most hallowed of the department’s divisions and the reservoir of officer talent from which all, or nearly all, of the department’s commanders are promoted, boasts 19 white members and one Hispanic. There are no African American members.

The Fontana Police Department has done little to welcome, or recruit, minorities into its ranks. Within police headquarters photos are displayed in plain view on the walls depicting white officers detaining minorities. There are also old photos taken where police are suited in riot gear surrounding minorities.

Reports of police brutality inflicted upon minorities in the community are commonplace. In conjunction with statistics showing a racial disparity in the department’s hiring and promotional practices, are anecdotal accounts of retaliation against department members who report discriminatory actions.

George Pepper, a former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, lived in Fontana in the 1970s and 1980s, using Fontana as the rallying spot for his organization.