By Carlos Avalos

Next Tuesday, August 22, 2017, David Moore, who had worked the last 16 years of his 23 years in law enforcement with the Fontana Police Department, will fight to be fully reinstated in his job as a police officer together with recovering five months of back pay when he comes before the Fontana City Council for a hearing.

Moore was ignominiously fired from the Fontana Police Department in March. That firing has a significant backstory, indeed a backstory with several layers.

The justification the department gave for cashiering Moore had nothing to do with using excessive force, nor pilfering items out of the department’s evidence locker, nor was he suspected or proven to have framed civilians with crimes they did not commit in the course of his work in the field or while he was carrying out investigations. And he was not charged with falsifying a police report. Indeed, Moore’s firing had nothing at all to do with his comportment on the job. Rather, his badge and service gun were taken from him because his wife, now his ex-wife, was listed as a beneficiary on the health insurance policy Moore was entitled to as one of his employment benefits. He had, the department maintained, phoneyed up a document pertaining to his health benefits policy. When the department’s internal affairs division came across this circumstance, he was placed on administrative leave, pending an investigation. It was not the first time he had been put on administrative leave.

During the investigation, Moore maintained his innocence and judicial records show that he marshaled proof in the form of a court order from a family law court judge that his wife remain as a beneficiary on his health plan until his divorce was finalized. Moore also produced a letter from his divorce attorney, which explained that he was acting on the advice provided by his divorce attorney. Despite his provision of those exhibits, Moore was terminated.

In effort to inflict more punishment on Moore, the Fontana Police Department denied unemployment insurance to him, contending that he intentionally committed fraud. Moore took the matter before an Unemployment Appeals Court. Two weeks ago, administrative law judge Catherine Leslie ruled in Moore’s favor with regard to his appeal for unemployment income. Records from that appeal stipulate that, “There was insufficient basis to establish that Moore willfully and intentionally breached his duty to his employer.” Next week, the Fontana City Council, sitting as the city’s de facto civil service commission will hear a fuller range of arguments as to whether Moore should be reinstated, including being reinstated with back pay.

The general contention is that the issue relating to keeping his wife on his health benefit account was merely a pretext, and a pretty poorly constructed one at that, to fire him.

Moore’s actual transgression had nothing to do with falsifying his benefits application and everything to do with his recurrent role as a whistleblower within the department.

A whistleblower is defined as a person who exposes any kind of information or activity that is deemed illegal or unethical. For the most part, whistleblowers are members within an organization rather than outsiders. While there are whistleblowers in both the corporate world and the public sector, the classic examples of whistleblowers are those within the public sector, generally government employees. Their positions and the authority they wield – limited or extended – vantages them to not only observe government and governmental operatives in action but endows them with a specialized knowledge of how government works, what the standard procedures are, how records and documentation are kept, what the political and bureaucratic lay of the land is. In short, they are insiders to some degree or another and they possess the knowhow, the data, the credibility and, most importantly the access to information, that allows them to reveal to the world, or at least a part of it, what is actually going on or what has gone on in the day-to-day function of that particular organization.

Some whistleblowers have purer motives than others. Some come forward out of conscience and something akin to altruism – a sincere desire to do what is right and make sure that others with power do not misuse that power. Others are whistleblowers because they themselves have been less than exemplary in their own behavior and action and use of authority and they have now been caught themselves or are on the brink of being caught and it now behooves them in some way to provide a wider context to the atmosphere in which their own misdeeds took place.

Whatever their motivation, whistleblowers are generally not in favor with their masters – their political masters or their professional masters or their employers. By whistleblowing, they are bringing attention to issues and behaviors those with authority beyond their own would rather remain below deck, off the radar screens, outside the consciousness of the public at large. With exposure of things that are not quite right comes demands for accountability and reform. Those holding the power and authority are not without recourse; they can bring that power and authority to bear. Those doing the whistleblowing almost always fall under the authority, within the purview or inside the bureaucratic reach of those being exposed, and those exposed are quite often at liberty to vector their power and bureaucratic control on those individuals who have exposed and embarrassed them. Bureaucratic infighting often takes the form of discrediting the whistleblower, subjecting him or her to exposure as well, and applying discipline or the force of law.

The most celebrated whistleblower within the last several years was Edward Snowden, the one-time Central Intelligence Agency employee who had become a contractor with the National Security Agency. In his role, Snowden learned that the government was overstepping its legal authority and violating – wholesale – Americans’ constitutional rights. He abided it for a time, but upon hearing the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, lie under oath to Congress on March 12, 2013 by denying the existence of the metadata collection systems Snowden knew existed, he took it upon himself to reveal, in a profound example of whistleblowing, the existence of those systems to the New York Times, the British newspaper the Guardian and to documentary maker Laura Poitras.

Snowden explained himself and the motives behind his actions, saying that when a person in the position of privileged access is exposed to much more information on a broader scale than the average employee, two of several things can happen. One of those is that the individual becomes inured of what he sees and knows and begins to consider it routine, justifiable and acceptable. The other reaction – one that is a common theme with whistleblowers – is to become disturbed and outraged. Such a reaction carries with it danger and life- or career- threatening implication. And it can bring the full force and authority of the government – the larger government and not just that branch of it about which the whistleblowing was done – down on the head of the whistleblower. In Snowden’s case, his whistleblowing touched on the National Security Agency. And, to be sure, the National Security Agency used its power and authority against Snowden, using its ability to monitor – whenever and wherever it was not thwarted by Snowden’s countermeasures – his every effort at communication through whatever means and to track his moves and whereabouts. But the NSA did not stop there. It networked with other branches of the U.S. Government to bring him to heel. The U.S. Department of Justice in secret lodged charges against him, unsealing them on June 21, 2013, at which point it was revealed he had been charged with two counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and further counts pertaining to the theft of government property. The U.S. Customs Agency revoked his passport. He transited to Hong Kong and hence on to Moscow, where Russia granted him asylum, and where he yet resides, while the U.S. Government remains intent on prosecuting him if he can ever be brought back. As for those whose violation of the law – such as Clapper who oversaw the illegal surveillance and then perjured himself before Congress – drove Snowden to become a whistleblower, the U.S. Government has given them a pass and they have gone uncharged, unindicted and unpunished.

So it was with Officer David Moore. He had been an exemplary officer with the Fontana Police Department. As an African-American on a police force whose members are overwhelmingly white, he worked hard to fit in within the Fontana Police Department after he took a lateral transfer from the Los Angeles Police Department in 2000.

Moore’s fate, at least as far as within the context of the Fontana Police Department, has become inextricably linked with that of a Hispanic officer with the department, Andrew Anderson, who has been with the department since 2002. Anderson too had begun his career with the LAPD.

Moore and Anderson are known for speaking out about what they perceive as unfair practices where they are employed. Not only were Moore and Anderson sensitive to the racial disparity within the department, they voiced their concerns about what they say is inadequate leadership within the organization. Moore often decried the cliques and subculture within the department, pointing out that certain individuals, usually Caucasian SWAT [special weapons and assault team] officers, were swiftly promoted. Moore also spoke openly about the convoluted promotional process, which requires candidates to privately campaign for positions within the department. This arbitrary promotional process allowed the administration to handpick those individuals who they felt “fit the overall goals of the department.”

Despite his outspokenness, Moore was for many years given glowing performance reviews. That has changed within the last few years, shortly after Moore eclipsed his 22nd year in law enforcement. The first incident occurred in November 2015, when Moore and Anderson, who lived in the same neighborhood in Hesperia, decided to check on the health and wellbeing of their elderly neighbor, Steve Olsen.

Two squatters had covertly moved into the elderly man’s house. Without paying rent, they assumed control over the elderly man and his home. They forced Olsen to live as a recluse inside of his own garage. Anderson and Moore reported the incidents of abuse to their department; however the matter was never investigated. The elderly gentleman would show up to gatherings with evidence of physical abuse about his face and body.

One night, after hearing sounds of distress coming from Olsen’s garage, Moore and Anderson, both police department supervisors at the time, did a welfare check on their neighbor. Once Moore and Anderson came onto Olsen’s property, one of the male squatters attempted to access a knife. Moore and Anderson restrained him.

Olsen was found unconscious inside his garage, slumped over the steering wheel of his car. The sheriff’s department, which provides law enforcement service to the City of Hesperia under a contract, was called. The responding officers addressed the matter, and cleared Moore and Anderson of any wrongdoing.

Olsen survived this incident, but would not be so fortunate in the months to come.

Moore and Anderson reported the incident as proscribed by their department policy, and solemnly warned the Fontana Police Department that if law enforcement did not intervene in the odd living arrangements at Mr. Olsen’s home, he would very likely soon be dead. Anderson and Moore’s assessment of the situation was disregarded by their supervisors with the Fontana Police Department, and those higher-ups decided against making an agency-to-agency request to the sheriff’s department to look into Olsen’s circumstance to ensure his welfare. Eleven months later, Steve Olsen died in the care of the two squatters.

The male squatter who was detained by Anderson and Moore complained to their employing agency, the Fontana Police Department. To Moore’s and Anderson’s mortification, the Fontana Police Department, without regard to the determination made by the sheriff’s department with regard to the initial call regarding their confrontation with the squatters, initiated an internal department investigation of their action. The Fontana Police Department relieved Anderson and Moore of duty and declared their conduct unbecoming to the department.

The Fontana Police Department suspiciously lost some of the initial recordings of the calls from Moore and the squatters. A memorandum was completed by a lieutenant, which was supposed to contain Moore’s verbal report of the incident. This memo was forwarded up the chain of command. The memorandum was filled with false statements and allegations which conveyed Moore and Anderson were not truthful and honest in their reporting. The recording which contained Moore’s actual verbal report of the incident was somehow lost. Under the direction of former Chief Rodney Jones, Moore and Anderson were accused of false and misleading statements. They were terminated and compelled to participate in an administrative hearing to keep from having their careers ruined.

During the hearing it was established that Moore and Anderson had been truthful. They produced their audio recording of what Moore actually reported the night of the incident to the lieutenant, to prove that their statements in fact were accurate. The audio recording and other evidence marshaled by them cleared them of lying. It further brought into question the integrity of the internal investigation process and the action of the chief.

As a result of this investigation, the officers were reinstated to full duty. In a face-saving gesture for the department, Fontana City Manager Ken Hunt gave them 30-day suspensions without pay. Moore and Anderson would not accept that punishment, asserting they had done nothing wrong in looking after their elderly neighbor and that there was no proof they had physically harmed the complainant. Anderson and Moore appealed the 30-day suspensions through an arbitration hearing.

During this hearing the city attorney accused Moore and Anderson of conduct unbecoming. After a short opening statement by Moore’s attorney, the city attorney asked for a brief intermission. The city attorney approached Moore with a settlement offer. The offer was to reimburse Moore of his lost wages from the 30 days suspension and accept a letter of reprimand, which would be eliminated within one year’s time frame. Attorneys for Moore stated he was close to accepting the offer however, in fine print he realized the city was asking to be excused universally from liability. More rejected the offer and decided to file a civil suit to clear his name and reputation.

In early 2016, Moore and Anderson fought back, filing suit against the department. Officer Moore was dealing with this lawsuit and still working at the department as a police corporal, an unenviable position to be in. According to sources within the department, Moore was hated by some of his peers, and he was encouraged by others. In the same time frame, his marriage was in the course of dissolving.

In the early months of 2017, officer Moore was put on administrative leave by Jones’ replacement as chief of police, Robert Ramsey. For the second time within two years officer Moore was fighting for professional survival, up against the police department he had spent more than two-thirds of his career with. Both the Chief of Police Robert Ramsey and City Manager Ken Hunt terminated Moore.

Since his termination, now five-month ago, Moore has done all he can to make ends meet. Fontana city officials have not just snatched away his livelihood they also deprived Moore and his family of health benefits.

Moore’s experience with the Fontana Police Department has not been unique.

Dave Ibarra, a two-time Iraq War veteran, worked at the Fontana Police department for ten years, from 1996 until 2006. While at the Fontana Police Department, Ibarra received many commendations for his actions while in the line of duty. While at the Fontana Police Department, Ibarra noticed a core difference within the police culture, whereby high ranking officers in the department favored, with very few exceptions, certain Caucasian members of the department. Those so favored were known as the, “Golden Boyz.” These well-connected Golden Boyz swiftly advanced within the organization. African American officers were not permitted within this inner circle. Anyone who opposed their accelerated career advancements, according to Ibarra, became a target of the department’s administration. When it came to promotions, the rest of the members in the department found themselves scratching the bottom of the barrel, looking for any leftovers the chosen ones bestowed upon them. The Golden Boyz were hand-selected in advance by the administration, the members of which were previously selected by those elite members who came before them. This resembled a fraternity or secret organization.

Some have noted the similarity between the eagle depicted on the Fontana Police Department patch above and the eagle on the Nazi military patch shown below.

Dave Ibarra during his tenure at the Fontana Police Department experienced harassment from his white colleagues. Ibarra on numerous occasions made formal complaints about his mistreatment. Ibarra claimed that on numerous occasions he encountered odd behavior on the part of his white colleagues. He maintains he came across Nazi literature and high ranking officers giving the Nazi salute. Ibarra at one point stayed within the chain of command in reporting these anomalies, calling out the “Good ol’ Boy System,” or “Golden Boyz,” and openly challenging his superiors. Eventually he became more vocal about the lack of diversity at the top of the department and with regard to the different treatment Fontana officers afforded the white citizens of Fontana as opposed to the minority residents of Fontana. Those reports did not result in the reforms Ibarra thought necessary, and in 2006 he submitted his formal resignation and moved on to a different department. At that time, some of the opposing Fontana administrators asserted that Ibarra was a lone, disgruntled employee. Ibarra’s contentions were borne out, however, by at least a half dozen officers who provided similar accounts or complaints of police brutality, racism, hostile work environment, favoritism and racial disparity within the ranks. Some of these officers were Chris Burns, Paul Martin, Ray Schneiders, Cliff Ohler, Kurtis Slotterbeck. and recently David Moore and Andrew Anderson. Most of these so called disgruntled officers were forced to resign or medically retire. Andrew Anderson was recently forced to retire after he testified against the department during depositions.

Dave Ibarra during his tenure at the Fontana Police Department experienced harassment from his white colleagues. Ibarra on numerous occasions made formal complaints about his mistreatment. Ibarra claimed that on numerous occasions he encountered odd behavior on the part of his white colleagues. He maintains he came across Nazi literature and high ranking officers giving the Nazi salute. Ibarra at one point stayed within the chain of command in reporting these anomalies, calling out the “Good ol’ Boy System,” or “Golden Boyz,” and openly challenging his superiors. Eventually he became more vocal about the lack of diversity at the top of the department and with regard to the different treatment Fontana officers afforded the white citizens of Fontana as opposed to the minority residents of Fontana. Those reports did not result in the reforms Ibarra thought necessary, and in 2006 he submitted his formal resignation and moved on to a different department. At that time, some of the opposing Fontana administrators asserted that Ibarra was a lone, disgruntled employee. Ibarra’s contentions were borne out, however, by at least a half dozen officers who provided similar accounts or complaints of police brutality, racism, hostile work environment, favoritism and racial disparity within the ranks. Some of these officers were Chris Burns, Paul Martin, Ray Schneiders, Cliff Ohler, Kurtis Slotterbeck. and recently David Moore and Andrew Anderson. Most of these so called disgruntled officers were forced to resign or medically retire. Andrew Anderson was recently forced to retire after he testified against the department during depositions.

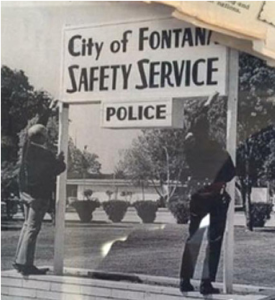

The Fontana Police Department for a time referred to itself as the safety service, or SS for short. Note the Teutonic Rune font used on the printing of the sign.

At one point, the Fontana Police Department renamed itself the Safety Service or the “SS.” Older officers and residents of the city say they remember during that time double lightning bolts could be seen on officers’ lapels, not unlike the lapel symbols of the Schutzstaffel of Nazi Germany, the SS, literally the “protection squadron.” In the 1950s Fontana police officers wore white uniforms. Older officers joked that the reason the uniform was white was so when officers got off of work they could take off their hats and put on their hoods. One of the police chiefs during this era was Ed Stout. Stout had been seen with a swastika tattooed on his arm and double lightning bolts on his back. Stout was known to have attended KKK meetings during his off-duty hours.

According to current and retired Fontana P.D officers certain images have been strategically and inconspicuously embedded within the culture of the Fontana Police Department, some of which are in plain sight; others are concealed on the bodies of officers in the form of tattoos, like badges of honor. The Fontana Police Department has a SWAT logo which takes as its primary element an eagle. To the casual observer, it might simply be an American bald eagle, a standard American symbol. This eagle does not look away way like the US Eagle. A closer look reveals that it more closely resembles the symbol of the Nazi Party, which has been adopted as emblem of many white supremacy groups. A small diamond is placed dead center on the Fontana Police Department’s winged SWAT logo. Several outlaw motor cycle gangs, as well as Nazi and white supremacy groups, use the diamond to symbolize the one percenters, or the small elite group of hardened soldiers who were selected to carry out key, specialized and dangerous assaults on specific targets.

In the Fontana police chief’s office there is a statue of a large owl with Germanic code beneath the logo. This same owl is visible on the patch worn on the arm of the rapid response team uniform, a unit founded by former chief of police Rodney Jones. On that patch, just below the owl there is Germanic Rune writing, which spells out RRT. All of this is a subtext, of course, and it is unclear, precisely, whether this symbolism is merely a paramilitary conceit or whether it signals, in a code to the initiated, a suggestion relating to white supremacy. We must remember, White supremacy groups cherish and admire the same Nazi paraphernalia, but they are extremely careful not to plagiarize fellow organizations.

Currently, Hispanics comprise roughly 69 percent of Fontana’s 212,000 residents. African-Americans comprise slightly more than ten percent of the city’s population. Nevertheless, the 194-member Fontana Police Department is composed of sworn officers who are predominantly white, such that it has never had more than four African American officers on the force at any given time. The department employs fewer than thirty Latino officers – roughly 15 percent of the force. The department’s prestigious special enforcement detail (SED), the most hallowed of the department’s divisions and the reservoir of officer talent from which all, or nearly all, of the department’s commanders are promoted, boasts 19 white members and one Hispanic. There are no African American members.

The Fontana Police Department has done little to welcome, or recruit, minorities into its ranks. Within police headquarters photos are displayed in plain view on the walls depicting white officers detaining minorities. There are also old photos taken where police are suited in riot gear surrounding minorities.

Reports of police brutality inflicted upon minorities in the community are commonplace. In conjunction with statistics showing a racial disparity in the department’s hiring and promotional practices, are anecdotal accounts of retaliation against department members who report discriminatory actions.

George Pepper, a former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, lived in Fontana in the 1970s and 1980s, using Fontana as the rallying spot for his organization.

The KKK was responsible for burning a black family alive in their home during the 1940s. Fontana was once a magnet for Nazi low riders, white supremacist skinheads and the WAR Party, the White Aryan Resistance. These groups co-existed with the police department, indeed thriving in what was for them a safe haven.

According to one of the department’s current lieutenants; “You see what is going on at the upper ranks of this department and you get discouraged. Good people are being taken advantage of, and no one wants to speak about it.”

One might call it a coincidence that David Ibarra, David Moore, and Andy Anderson have been fired, were encouraged or forced to leave, or were medically retired at the hands of the department they once were proud to serve, that all three were officially defined ethnic minority class members and that all three questioned their superior officers and the department’s policy.

Unproven allegations of racism and white supremacy within the halls of the Fontana Police Department are contained in the lawsuit brought by David Moore and Andrew Anderson now wending its way through San Bernardino County Superior Court. The Sentinel welcomes any response the Fontana Police Department is prepared to give to the allegations in that lawsuit.

Ted Hunt, a Fontana Police Officers Association representative has said the pool from which the department has to pick and keep hard working officers is diminishing. It has been alleged that there is only one outcome for a Fontana police officer who blows the whistle: termination preceded by ostracism.