By Mark Gutglueck

By Mark Gutglueck

There is less than perfect agreement among historians with regard to the year of Don Antonio Maria Lugo’s birth. Multiple sources say he was born in 1775. Another dates his birth as occurring in 1778. There is a further discrepancy with regard to whether he was born in the New or Old World. The City of San Bernardino’s website states that he was born in Spain. H. D. Barrows, who knew him and interviewed him extensively in 1856, which was some four years before Lugo’s death, in 1896 wrote Lugo “was born at the Mission of San Antonio de Padua, of Alta California.” Mission San Antonio de Padua was located in what is present day Jolon, California, which at that time was within New Spain. It is perhaps because California was at that time land under the crown of Spain that the confusion as to Lugo’s birthplace exists. There is no dispute that he was the seventh son of Francisco Salvador Lugo or that he became one of the largest land-owners and stock raisers outside of the missionary establishments in California.

In 1795, Don Antonio married Dolores Ruis, by whom he had ten children. After her death, he married as his second wife Maria Antonia German, by whom he had several children.

As a young man, he served for 17 years as a soldier of the king of Spain in the garrison at the Presidio of Santa Barbara.

Sometime around 1807, he took a few head of horses and cattle south to Los Angeles, and engaged in a small way, as his service as a soldier had not yet ended, in the business of stock-raising along the banks of the Los Angeles River. In 1810, Corporal Lugo received his discharge and settled with his family in the Pueblo de Los Angeles and was given a grant title to settle on seven leagues of land, or 30,998.8 acres, what became known as the Rancho de San Antonio. In 1813, the same year his son José del Carmen Lugo was born, he constructed a hacienda on that property near the present City of Compton. The rancho stretched from the Dominguez or San Pedro Rancho, one of the four most ancient grants in Alta California, nearly to the low range of hills separating it from the San Gabriel Valley, and from the eastern boundary of the Pueblo Ranch to the San Gabriel River, according to Barrows. It was considered one of the finest cattle ranges in the territory, with an abundance of water on it and on both sides of it, as the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers had not yet been converted for irrigation purposes, and there were lines of live willows extending along their banks nearly to the sea.

He served as Alcalde or Mayor of Los Angeles from 1816 to 1819.

In 1818, according to an account by Stephen C. Foster, “the pirate Bouchard had alarmed the inhabitants of this coast, and Corporal Antonio Maria Lugo received orders to proceed to Santa Barbara with all the force the little town could spare.” Lugo, expecting the pirates would land at or near the Ortega Ranch, descended upon them rapidly and unexpectedly there, taking several of crew members captive, including one named Joseph Chapman and another described by Foster as “a negro named Fisher, the only one of the rogues who showed fight.” Lugo employed one of his men, a Corporal Ruis, to lasso Fisher, who was “brought head over heels, sword and all” and bound to Santa Barbara, where he was left in the custody of those there. Both Chapman and Fisher spoke English.

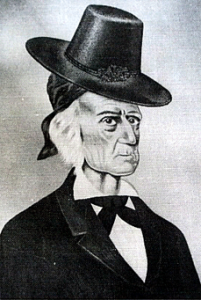

Some two weeks later, Lugo started with Chapman for Los Angeles, where according to Foster, “Dona Dolores Lugo, (wife of Don Antonio,) who, with other wives, was anxiously waiting, as she stood after nightfall in the door of her house, heard the welcome sound of cavalry and the jingle of their spurs as they defiled along the path north of Fort Hill. They proceeded to the guard house, which then stood on the north side of the Plaza across upper Main Street. She heard the orders given, for the citizens still kept watch and ward; and presently she saw two horsemen mounted on one horse, advancing across the plaza toward the house, and heard the stern but welcome greeting, ‘Ave Maria Purlsima,’ upon which the children hurried to the door and kneeling, with clasped hands, uttered their childish welcome, and received their father’s benediction. The two men dismounted. The one who rode the saddle was a man fully six feet high, of a spare but sinewy form, which indicated great strength and activity. He was then forty-three years of age. His black hair, sprinkled with gray, and bound with a black handkerchief, reached to his shoulders. The square-cut features of his closely shaven face indicated character and decision, and their naturally stern expression was relieved by an appearance of grim humor — a purely Spanish face. He was in the uniform of a cavalry soldier of that time, the cura blanca, a loose fitting surtout [a frock coat, of the kind worn by cavalry officers over their uniforms in the 18th and early 19th centuries], reaching to below the knees, made of buckskin, doubled and quilted so as to be arrowproof; on his left arm he carried an adargi, an oval shield of bull’s hide, and his right hand held a lance, while a high-crowned, heavy vicuna hat surmounted his head. Suspended from his saddle were a carbine and a long straight sword. The other was a man about twenty-five years of age, perhaps a trifle taller than the first. His light hair and blue eyes indicating a different race, and he wore the garb of a sailor. The expression of his countenance seemed to say, ‘I am in a bad scrape; but I reckon I’ll work out somehow.’ The senora politely addressed the stranger, who replied in an unknown tongue. Her curiosity made her forget her feelings of hospitality, and she turned to her husband for an explanation. ‘Whom have you here, viejito (old man)?’

– ‘He is a prisoner we took from that buccaneer — may the devil sink her — scaring the whole coast, and taking holiest men away from their homes and business. I have gone his security.’

-‘And what is his name and country?’

-‘None of us understand his lingo, and he don’t understand ours. All I can find out is, his name is Jose and he speaks a language they call English.’

-‘Is he a Christian or a heretic?’

-‘I neither know nor care. He is a man and a prisoner in my charge, and I have given the word of a Spaniard and a soldier, to my old comandante for his safe keeping and good treatment. I have brought him fifty leagues, on the crupper behind me, for he can’t ride without something to hold to. He knows no more about a horse than I do about a ship, and be sure and give him the softest bed. He has the face of an honest man, if we did catch him among a set of thieves, and he is a likely looking young fellow. If he behaves himself we will look him up a wife among our pretty girls, and then, as to his religion the good Padre will settle all that. And now, esposita mia (good wife), I have told you all I know, for you women must know everything, but we have had nothing to eat since morning; so hurry and give us the best you have.’”

According to Foster, Lugo’s decision to treat his Yankee prisoner, Joseph Chapman, humanely turned out to be a propitious one. Chapman became the first English speaking settler in Los Angeles. He assisted Lugo in bringing timber down from the mountains, with which a a church was constructed. Within a few years he was able to speak Spanish to the point of being understood. Having mastered horsemanship, Chapman accompanied Lugo to Santa Barbara, where an introduction was made to Sergeant Ortega and Chapman then took as his wife Sergeant Ortega’s daughter, Senorita Guadalupe Ortega. Lugo stood as sponsor at the wedding; Lugo then set out with the newly-nuptialed Mr. and Mrs. Chapman on horseback on the long road from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles. Chapman and his bride rode the same horse.

In 1821, Mexico obtained independence from Spain. All the territories of New Spain, including California, fell under the dominion of the new country and became subject to Mexican rule.

In 1833 and 1834, Lugo served as the juez del campo, or judge of the plains, for the Southern California region. In this office he was called upon to settle differences between rancheros relating to conflicts over boundaries, the ownership of cattle, and the like. His power of adjudication was absolute; there was no appeal from his decisions. His appointment as judge was a remarkable one in that Lugo could neither read nor write.

With three of his sons, Don Antonio Lugo purchased for $800 in hides and tallow the Rancho San Bernardino from the Mexican Government in 1842. Rancho San Bernardino consisted of Colton, San Bernardino, Highland, Loma Linda, Redlands and Yucaipa. Lugo was able to close the dealt because the Mexican government wanted to secure the land from outside encroachers and hostile Indians. Selling it to Lugo, who intended to use it for cattle raising and other agricultural purposes, suited the government’s goals.

An assistencia – an extension of the San Gabriel Mission – had been established near what is the present day boundary between Redlands and Loma Linda by Spanish priests in 1819. It was called the San Bernardino de Sena Estancia. But the Mexican Government had forced the Spanish missionaries out of the missions and the assistencia in the 1820s. When Lugo became interested in the San Bernardino Valley, he had both altruistic and selfish concerns with regard to the abandonment of the assistencia. The indigenous population was subsisting on the grounds of the assitencia, in dire poverty and in danger of perishing. Lugo was conscious, as well, of the tendency of some native tribal members to engage in marauding of the cattle herds. Shortly after he bought the Rancho, Don Antonio appealed to the governor to assign Father Jose Zalvidea, formerly of the San Gabriel Mission, to set up an operation at the assistencia, and in so doing alleviate the suffering of the Indians.The text of his letter, which he dictated but which was written down by a scribe, provides an insight into Lugo’s character, his regard for the physical well-being and souls of the Indians intermixed with his effort to ensure that a church and armed parish priest with a flock of Christian devotees might stand as a bulwark against hostile Indians and make sure his livestock were safeguarded. The governor never responded to that request, and so his son made his home at the assistencia, where he offered employment and protection to the Indians there.

At the San Bernardino Rancho, the numbers of cattle grew as they had at the San Antonio Rancho.

During his life, Lugo lived under Spanish rule, then Mexican rule and then American rule. In his orientation, and throughout his life, he remained, according to H.D. Barrows, “in most respects as thoroughly a Spaniard as if he had been born and reared in Spain.” Though he functioned as a member of both the Spanish and Mexican establishments, he bridled though did not rebel under the dictates and impositions of the Mexican governmental authority. After Mexican American War and the Bear Flag Revolt placed California in the hands of the Americans, he remarked “‘So the Mexicans have sold California to the Americans for $15,000,000, and thrown us natives into the bargain? I don’t understand how they could sell what they never had, for since the time of the king, we sent back every governor they ever sent here. With the last they sent 300 soldiers to keep us in order, but we sent him with his ragamuffins back too. However, you Americans have got the country; and must have a government of your own, for the laws under which we have lived will not suit you.”

According to Barrows, “He looked upon the coming of the Americans as the incursion of an alien element, bringing with them as they did, alien manners and customs, and a language of which he knew next to nothing, and desired to know less. With ‘Los Yankees,’’ as a race, he, and the old Californians generally, had little sympathy, although individual members of that race whom from long association he came to know intimately, and who spoke his language, he learned to esteem and respect most highly, as they in turn, learned most highly to esteem and respect him, albeit, his civilization differed in some respects radically from theirs.”

Barrows said, “He retained to the last the essential characteristics which he inherited from his Spanish ancestors; and although he had as was very natural no liking for Americans themselves, as a rule, or for their ways, nevertheless, he and all of the better class of native Californians of the older generations did have a genial liking for individual Americans and other foreigners, who, in long and intimate, social and business intercourse, proved themselves worthy of their friendship and confidence. His daughter,Maria Merced Lugo, married Stephan C. Foster, an American who served in the California Constitutional Convention in 1849, and was elected to the State Senate and was elected as the first mayor of Los Angeles in 1856 under United States military rule, and was later elected for four terms to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

Lugo remained engaged as a California cattle baron, living primarily in San Bernardino, When the Mormons arrived in California in 1850, he entered into negotiations with them and in 1851 Sold Rancho San Bernardino to them for $77,000.

After the sale of San Bernardino, the Lugos returned to Los Angeles. In 1860, Don Antonio Maria Lugo died at his hacienda on Rancho San Antonio near present day Compton.

SBCSentinel

News of note from around the largest county in the lower 48 states.