By Mark Gutglueck

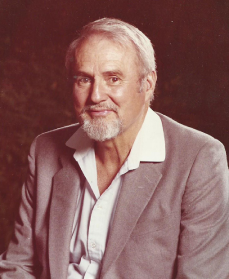

Donald Maroney, one of the longest serving city attorneys in San Bernardino County and California history, died on December 3.

Maroney’s was a brilliant mind that was channeled into the arena of law for 46 years.

Before attending law school or passing the state bar, Maroney racked up a series of accomplishments that distinguished him and his intellect. By his early trajectory he seemed destined for a career in high finance or the field of banking at the international level or with the Federal Reserve, but a handful of events would shift his focus and redirect him toward a legal career.

Even before he was born, Donald Maroney was recognized as precious human cargo. He was born in a hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah, to which his father, George Maroney, had driven his mother, Faith Maroney, because at that time the maternity ward in the hospital at Boise, Idaho, where the couple resided, was less thoroughly equipped and boasted a less-experienced staff than the one across the state line.

George Maroney was the county agent in Boise. Faith Maroney was a former concert pianist who worked as a piano teacher. Donald Maroney was six years old when he moved with his parents to California, where George Maroney would obtain a professorship at Pasadena City College, teaching chemistry. In 1930, the family settled in Modesto, where George Maroney taught chemistry, biology and physiology and coached the golf team at the junior college there. In high school, Don Maroney proved himself a gifted tennis player, earning his varsity letter in the racket sport. He was also a consummate violinist, meriting the position of first chair in the high school band. Upon graduation, Maroney matriculated at the University of California at Berkeley, where he majored in economics, graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1942.

At that point, as was the case for practically every American of his generation, Don Maroney’s life was interrupted by the Second World War. In 1943 he joined the Navy and was accepted into officer training school at Northwestern University near Chicago and was on track to becoming a PT boat captain. By his own account, he grew skittish at the prospects of commanding such a small vessel on the open seas in the midst of a world war in which the mortality rate for such crews was considerably higher than that of other naval recruits. He tested out, based upon his expertise in economics, to be a supply officer. He was sent for further training at Notre Dame University in Indiana and to Harvard for administration courses, finally making it into the field of action as a lieutenant in the Pacific in 1944, where he was detailed to the 102nd Construction Battalion (the Seabees) in Finschhafen, New Guinea. While there, he was given the assignment of constructing an open air entertainment amphitheater, which he carried off, promptly, efficiently and under budget. At the maiden performance at the amphitheater, however, a 16-foot long, 45-pound python slithered out of the jungle and into the stands, seemingly intent on making a meal of one of the audience members. The commotion interrupted the performance while the uninvited drama crasher was hauled aside and shot. Decades later, Maroney would recollect with consternation his initial alarm at what had occurred and his later resentment at being called on the carpet by a superior officer over the incident.

Sometime after Douglas MacArthur’s October 1944 return to the Philippines, the U.S. Navy recommitted to establishing its military base of operations there and Maroney, with the Seabees, was given a billet at Subic Bay. As the war was winding down, in mid-1945, Maroney was given a stateside assignment in Stockton at a POW camp for Germans captured in the European Theater. Officially, he was the mess officer at that facility. Nevertheless, as with nearly all of his activity, Maroney would go beyond the letter of his duty, and he was instrumental in humanizing the somewhat dehumanized conditions of confinement to which the soldiers of the Nazi regime found themselves consigned. Calling upon his own accomplishment as a musician, Maroney obtained authorization to recruit from among the prisoners those with musical ability, and thus formed a prison orchestra, to the members of which were entrusted instruments according to their particular talent. In this way, performances within the walls of the prison as well as in venues outside the camp were given. The participating prisoners were provided an outlet for their energy, all prisoners found a respite from their soul-deadening confinement, and the local populace abutting the camp was favored with entertainment and an illustration of the culture and refinement of the German Volk their adherence to Nazism notwithstanding. Perhaps most importantly, the participating musicians were vouchsafed a headstart on being reintegrated back into society and civilization.

After the war had been concluded, Maroney was discharged from the Navy as a lieutenant commander and he too would find himself faced with the same challenge of reintegrating back into a society now jaded with the horrors of the most consuming war in history and its horrific conclusion against the backdrop of the deaths of some 73 million combatants and civilians. Accompanying the positive accomplishment of the defeat of Nazism and Fascism was the negative consequences of the advancement of Soviet Communism. Maroney and his fellow inductees were now faced with returning to a place between the Atlantic and Pacific not much different from the place they had left, one yet beset with the same social ills that had plagued America before the war which in no way had been remedied by the war. By the end of 1946 he had settled upon pursuing law as a career and was attending USC Law School.

He graduated from USC Law School in 1949 and immediately passed the bar. He went to work for Henry Busch, who was then Ontario’s city attorney. He was initially paid $100 a week.

In 1950, he married Loris Mercer, The couple raised eight children born between 1951 and 1965: Gay-Lynne Maroney; Robin Maroney; Raymond Maroney; Susan Maroney, who later married Lee Hudson; John Maroney; and Neal Maroney. Don Maroney had established a home in Upland and all six of his children were born at San Antonio Hospital.

Maroney learned the ropes of the legal profession under Busch, who later, in addition to being Ontario’s in-house counsel, became the city attorney for Upland. After Busch was elevated to the bench, Maroney became Upland’s city attorney, a position he then held for a third of a century.

Maroney loved practicing law and going to the mat for his clients. His habitation of the adversarial system, however, did not blind him to the reality that coming to an accommodation between litigants often represents a far less costly outcome than litigating many matters to a conclusion, and he had perfected the art of compromise to a science. His advice to the junior members of his firm, as well as the municipal department heads in Upland who had found themselves enmeshed in an unforgiving legal confrontation was “just handle it,” which was very often construed as “make a face-saving settlement acceptable to all parties.”

He once told a newspaper reporter who had been informed that Maroney had “never lost a case” that the reporter needed to find more reliable sources of information because, Maroney said, he had lost many a case.

For the last thirty years of his career as an attorney, Maroney was in partnership with Barry Brandt, under the aegis of the firm Maroney and Brandt, at that time Upland’s largest law firm. The relationship between Maroney and Brandt started out as an adversarial one in which they each represented parties in litigation against one another.

According to Barry Brandt, “I was a much younger man and had just come out of the Judge Advocate General’s Office with the Air Force and was practicing at a local law firm. To tell you the truth, I was not completely happy there. Don and I had a case together and as the opposing attorney, he had moved to assign a deposition at a different office and when I showed up for the deposition, Don wasn’t there. I was miffed, I must say, and when I called him up, he was completely apologetic. He bent over backwards to undo the problem. He had inadvertently offended me, but what he did was not out of arrogance. He was something like 13 years my senior and he could have pushed me around on the basis of that, but he did not. That case brought us together. You can learn more about somebody in the course of a trial than just about anywhere else. When you are in battle, the way you behave when you’re in the foxhole tells a whole lot about you and your character. During that trial, I said to myself ‘I want to be around this guy more often’ and when the opportunity came for us to go into practice together, I took it.”

Their firm, Brandt said, dealt in a wide spectrum of the law. Maroney’s line of expertise was in municipal law, business law and probate law. Maroney’s longest lasting, largest and most consistent client was the City of Upland. Brandt said, “Don and I had a lot of business clients between the two of us.”

According to Brandt, “Don had a razor-sharp mind, but he had a real talent for keeping you from thinking he did. He didn’t want you thinking he was smart. He had this self-deprecating manner. But for me, I never forgot who was the wise old sage and who was the understudy.”

There was an element of cunning and stealth to Maroney’s practice of law, Brandt said, which he himself would later benefit from. “We were coming up on a trial and he gave me the file on the case, together with a document that was about to be filed. He told me to read it. I looked it over and said, ‘This is really bad. You can’t file this.’ Don said, ‘Why not?” I said, “Because the opposing lawyer will think you’re an idiot.’ Don said, ‘That isn’t so bad, is it?’’

Brandt learned from his partner in other ways.

“Relatively early on, he was telling me about how he had gone into Los Angeles on a settlement,” Brandt said. “The plaintiff had put a lien on Don’s client’s property. The case was on the brink of being settled. The other lawyer asked Don, ‘Did you bring the check?’ Don said, ‘Yeah. It’s right here.’ Don gave the lawyer the check. The lawyer looked at it and said, ‘Everything appears to be in order. It was nice to meet you.” Don said, ‘Well, then, we need a release.’ The lawyer said, ‘We’re not going to give you a release.’”

Brandt continued with the narrative, “I was still a pretty headstrong young man at this point and I’m thinking about how I would have reacted. I can tell you, I would not have just backed down, and no one would have pulled anything like that on me. No matter what would have happened, I wouldn’t have let another lawyer just walk away with a check like that. At this point I’m upset with Don for letting himself get pushed around. So I asked, ‘What are you going to do?’ Don said, ‘I already did it.’ I said to him, ‘What do you mean?’ Don said, ‘I just said to him, “You know, I’m just a simple country lawyer. This isn’t the first time I’ve been had like this. You really got me,’ and took a step back. He let his guard down when I said that, and I reached out and grabbed the check and put it back into my pocket under my vest. I told him, “When I get the release, you’ll get the check.”’”

Brandt offered another vignette of Maroney in action. “We had a case in Pomona and we were there for a trial setting conference,” Brand said. “Don said he was making a motion for nontrial, to outright dismiss the case. At once, the judge ordered us into chambers. So there we were, in chambers – the judge, Don and I and plaintiff’s counsel – and the judge, who was obviously upset, said ‘What do you mean?’ Don said, ‘Everything he has cited is plain wrong, Your Honor, and you’ll just have to dismiss this case.’ The judge asked why. Don said, ‘With regard to this part, on technical grounds. Look at sections 2840 through 2848 (or whatever it was) and you’ll see why.’ So the judge asked about another one of the causes of action. Don said, ‘Well, that’s covered by Smith vs. Jones, 1937 (or whatever it was). It continued on like that for a few minutes with Don just narrowing the case more and more. Finally, the judge said to the plaintiff’s attorney, ‘It looks like he’s right. I’ll give you ten days to answer on all of those points.’ And ten days later, he dismissed the case.”

Despite Maroney’s ability to tear the opposition’s case to shreds on legal or factual grounds, Brandt said that Maroney had forbearance and empathy, recognizing the imperfections in the legal system and was unwilling or constitutionally incapable of using the law as a cudgel to beat anyone, or just about anyone, into the ground. “He was a peacemaker and dealmaker,” Brandt said. He kept his clients and the city and the people his clients went up against out of vendettas and paybacks. I keep coming back to what his mantra was: ‘Just handle it.’”

In 1971, Maroney moved with his family to Fallbrook, on property that had 20 acres of avocado trees and 25 acres of orange and lemon trees. The Maroney brood, Don and Loris and four of their six children who were not at that point old enough to be attending college lived in a trailer on the property for nearly four months while a house was built. Don was required to make an-hour-and-a-half commute to work at that point.

In 1978, the Maroneys sold the avocado and citrus farm in Fallbrook and moved to Corona.

For three decades, Maroney was a mainstay at Upland City Council meetings. Years later, a position for the city attorney would be reserved for the city attorney and city manager on the council dais, but in those days, Maroney would observe, and on occasion participate in, the proceedings from a position in the first row of seats on the left side of the council chambers. Maroney would sit upright, usually to the immediate right of the city manager. Soon after recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and the audience was seated, the meeting proper would begin, first with Maroney reporting on any action or non-action taken during the closed door session of the council immediately prior to the public meeting. Voting on the consent calendar would ensue, followed by other items of civic business and/or public hearings. Sometime during the consideration of the consent calendar, Maroney’s eyes would close and he appeared to be asleep. If ever an issue meriting legal attention surfaced during discussion, however, Maroney’s eyes would open and he would offer ample indication through his analysis and comment that he had been hyperconscious throughout.

In 1981, with the last of their children having achieved college age, Don and Loris moved from the large house in Corona to Hacienda Heights.

A challenge that Upland, and therefore Maroney, faced in the 1980s and early 1990s, was the nepotism represented by the presence of Frank Carpenter on the city council and the status of Carpenter’s wife, Dee, as Upland’s elected city clerk. Both were entitled to hold their positions as a consequence of a voter mandate. Yet conflicts manifested and Maroney had to deal with some prickly issues, which required tact and diplomacy, as well as the ability to resolve contentions quietly and out of the public limelight without embarrassment to either husband or wife, without endangering his own position and while keeping the public’s interests from being intruded upon. Maroney would face a similar challenge in the 1990s, when Gail Horton was a member of the city council and her husband, John Scanlon, was fire chief.

In addition, Maroney would also need to deal with headstrong councilmembers and mayors in Upland during his tenure as city attorney, such as Bob Nolan, whose political reach exceeded their legal grasp. Maroney, skillfully, was able to conform their action to the law, requiring them, on occasion to trim their sails, yet somehow maintaining his position as city attorney, despite the consideration that he served at their pleasure and could be terminated by a simple vote of three of the council’s members at any time.

In 1983, Maroney and Loris separated. Don moved to Upland. Soon thereafter, the couple divorced. Maroney, seemingly overnight, became a target of virtually every predatory female over the age of 30 on the eastern end of the San Gabriel Valley and the entirety of San Bernardino Valley. Some were more aggressive than others. Many, it would turn out, had teenaged or adult sons who had fallen afoul of the law and were seeking legal representation for their offspring. Others saw Don as their ticket to riches or social standing, as he might instantly transform one of them into the spouse of Upland’s premier lawyer. One outwardly attractive and alluring woman appeared to be making considerable headway in this regard and was sharpening her claws with a mind of sinking them deeply and securely into Maroney’s flesh. One evening, as the couple was engaged in a serious discussion, which contained a hint of permanence and monogamy, the woman, daringly, asserted she had very high standards and asked if Maroney was prepared to do what it would take to keep her. This broke the giddy air of fascination with which she had been beguiling her prey, and Don adroitly disengaged himself from her thereafter.

In 1994, Don, at the age of 74 was no longer playing tennis and had moved to Pinion Hills in the desert just northwest of the Cajon Pass. At that point he was felled by what was termed a “baby stroke.” This hampered his function somewhat, but not completely. He did not remain in Pinion Hills long, thereafter, moving in 1995 to Oceanside. The following year, he retired for good as an attorney. When he left as Upland’s city attorney, the city would award him a plaque with the words “Just handle it.” A handle was attached to the plaque.

Shortly after he retired, he married Loretta Roknian, the widow of a former client. They relocated to Upland. Don quickly recognized the union was an unwise one and the couple were separated for more of the two years their marriage lasted than they were together. The divorce finalized, with Mrs. Maroney, nee Roknian, realizing very little in the way of profit from the short term nuptials.

Once he was no longer in the thick of legal issues, he said, more than once, that he wanted to take up being a college student once more, and study auto mechanics.

In 2000, Maroney moved to Apple Valley, where he remained for the remainder of his life.

On occasion, Maroney reimmersed himself into public issues, in particular in Upland. After his departure, the City of Gracious Living had careened into scandal following the election of John Pomierski as mayor and the establishment of a political machine that used as its capital the proceeds from bribes paid to ensure the approval of projects and proposals being processed at Upland City Hall. From time to time Maroney wrote missives to Upland elected officials, making observations of the anomalies he detected, warning that things were amiss or offering his advice as to how the city should proceed.

“He was just a remarkable guy,” said Brandt. “He was a gentleman’s gentleman and his guiding principle was kindness. He had six kids and he looked after them. There was some illness in his family and he always made sure those things were taken care of. He retired before I did and was living up in Apple Valley and I would go to see him. He had been bedridden for a few months earlier this year and his speech was impaired. But a few weeks ago, he seemed to be getting better. He was 96 and it seemed like he might make it to 100. Last week, he took a turn for the worse.”

There was nothing dramatic at the end. Maroney went to bed on Friday night and never woke up.

Maroney is survived by his children: Gay-Lynne Maroney, Robin Maroney, Raymond Maroney, Susan Maroney Hudson and her husband Lee, John Maroney and his wife Jennifer, Neal Maroney and his wife Lisa; 4 grandchildren, Elliot Maroney, Emily Aprea, Kevin Maroney, Courtney Maroney; and 3 great grandchildren. Don was married 33 years to the late Loris Mercer.

SBCSentinel

News of note from around the largest county in the lower 48 states.