By Mark Gutglueck

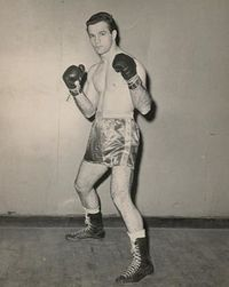

It is with no little degree of personal sadness that I am now tasked with reporting to the Sentinel’s readership that boxer Tony Valenti, who was based in Southern California for two years and fought 15 of his 34 professional fights here, has died.

For even those in my generation, Tony was a relatively obscure athlete and part of Americana. His heyday was confined to the 1960s. Those who followed the sweet science closely in those days most likely knew of him. The rest of us who were only fair-weather boxing fans who focused on the big names in the heavyweight division for the most part did not take special notice of him. He was a middleweight. Indeed, he was a pretty good one, gauging by his record. He was twice the USA Middleweight New England title holder.

I met Tony when my brother and sister-in-law welcomed him into their home during the 2015 Christmas Holiday. I spent hours in conversation with him on the night before Christmas and then much of Christmas morning talking with him. Our conversation would have continued, but I spent virtually all of Christmas afternoon 2015 in an airplane with three of my friends flying low over a huge selected swathe of the Eastern Mojave Desert, making pass after pass, trying to see if we could spot the Lost Dutch Oven Mine. That will have to be a story I relate more fully some other time.

Tony was born on April 13, 1940.

His debut as a professional fighter came on October 3, 1961, against John Kilmer in New Bedford. He won on a knockout in the third round.

After that first bout, Valenti moved to California, settling in Alhambra, where to hold body and soul together, he opened a pizzeria, dividing his time between baking Italian pies and training.

He won his first fifteen pro fights. His sixteenth fight was against Teddy Shores at the Moulin Rouge in Hollywood. They fought to a draw.

In his next fight, against Willie Turner, he registered a technical knockout.

Against the advice of some, who said he should have gotten a bit more seasoning before moving up to the next level, Valenti pushed himself to reach the ranks of the top tier fighters in his class. In his eighteenth fight, on September 12, 1963, he took on one of the three or four top contending middleweights in the world, the brutishly powerful Argentine, Juan Carlos Rivero, at the Olympic Auditorium. Tony suffered his first defeat at the fists of Rivero, a technical knockout that came 52 seconds into the fourth round. In the first three rounds, Rivero was relentless in throwing body shots, flurries of as many as six at a time. Less than a minute into the next round, Rivero, following another multitude of body shots, landed a left hook to Tony’s chin, leaving the American out but yet on his feet, prompting referee Tommy Hart to stop the fight.

At the end of 1963, Valenti returned to Massachusetts, fighting out of Boston. He won his next seven fights, including a technical knockout of Jimmy Beecham, the one-time USA Middleweight Pennsylvania title holder, at the Arena in Boston on October 5, 1964.

In his 26th fight, on December 14, 1964, Valenti lost for the second time as a professional, a split decision at the Boston Garden to Isaac Logart, the former Cuban middleweight champion.

Tony’s seven years as a professional boxer had the quality of two bifurcations. In one of those divides, he did the fighting at the beginning of his career out of Southern California and the fighting toward the end of his career out of Massachusetts. There was also a hiatus in the middle of his career that went into effect after his ninth fight after he was based on the East Coast. He abruptly stopped fighting after his victory over Clyde Taylor, a technical knockout, at the Boston Garden on March 27, 1965. He was idle the rest of that year, all of 1966 and nearly three-quarters of 1967.

On September 29, 1967, Tony returned to the ring after a 30-month layoff, in this case at Shea Stadium in a four-round exhibition bout, going up against the Argentine fighter, Juan “Butcher Boy” Botta. He floored Botta in the second round for a mandatory eight count and won a unanimous decision.

His career was remarkable from at least one standpoint, that being that it reached its zenith very near the end. When he resumed fighting in 1967, he seemed more determined than he had been previously to achieve a title shot. During his final year in the ring, he fought for the USA Middleweight New England title four times, winning it twice.

His first title fight occurred on December 11, 1967, an eight-round affair against Willie Munoz at Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He lost on points.

Seven months later, on July 11, 1968, after Munoz had vacated the title, Valenti met Bob Whitehead at the Exposition Building in Portland, Maine to slug it out for the New England title. In a pitched, hard-fought 10-round contest, the fight appeared even or that Whitehead was slightly ahead on points until Valenti knocked him down in the 10th round, and Tony prevailed in a split decision to capture the crown.

Two months later, on September 11, 1968, at the Silver Slipper in Las Vegas, he got into the ring for ten rounds against challenger Ferd Hernandez, the former co-holder of the World Boxing Association Middleweight title, with the USA Middleweight New England title on the line.

For Hernandez, this would be his last professional fight, the cap to a career in which he had fought four world champions, those being Luis Manuel Rodriguez, Sugar Ray Robinson, Nino Benvenuti and Denny Moyer, going the distance with all and winning a split decision against Robinson. Hernandez won the fight and the New England crown in a unanimous decision.

The championship was vacated with Hernandez’s retirement. On Halloween night 1968, in a 12-round bout against Jimmy Ramos at the Roseland Ballroom in Taunton, Massachusetts, Valenti successfully fought to regain the title, doing so in a split decision.

Just fifteen days later, after Valenti had flown to Los Angeles, he fought Rocky Hernandez at the Olympic Auditorium. The winner was to get a match-up with the leading middleweight contender, Andy Heilman, which had the potential for setting up a world middleweight title fight. Valenti lost in a technical knockout one minute and 52 seconds into the fourth round when referee Lary Rozadilla stopped the bout after Tony was knocked down for the fourth time. At that point, Valenti called it a career.

In 34 fights, he won 28 lost 5 and had one draw. At 5 foot 8 inches tall, the lowest weight recorded at a weigh in for him was 151 pounds prior to his bout against Tiger Williams at the Las Vegas Convention Center on December 8, 1962. His heaviest showing was for the fight he had against Sonny Moore at Sargeant Field in New Bedford, Massachusetts on July 14, 1964, when he weighed in at 164 pounds.

He was 28 years old when he hung up his gloves. There is something to be said for that, and I am about to say it.

Those I come into contact with have seen my cauliflower ears and know that I spent some time in the ring myself. I was never at Tony’s level. I shudder at imagining what someone like Ferd Hernandez or Juan Rivero or Tony would have done to me if I had squared off against one of them at their peak or even their nadir. Still, as an athletic challenge, boxing can be addictive. It’s no fun, really, getting punched in the nose, but there is something enlivening about slipping punches, making your opponent miss, and not getting punched in the nose. The idea is to hit and not get hit, or get hit as little as possible. Still, it is a young man’s game. Inevitably, if you stay in the sport, you are going to get hit and, occasionally at least, hit hard. Every time you get hit, you lose a little. At first it is imperceptible, but over time, it is cumulative. There is a degree of ego involved. Even at my advanced age, I still imagine – imagine – that I can slip punches. I even fantasize that I might be right. I am not the smartest guy out here, but I’m still sharp enough to recognize that I do not want to get into the ring and find out that I can’t do what I imagine I can still do.

When I met Tony at my brother’s house, he was 75 years old. I would estimate that he was right at, or maybe even a little bit below, his fighting weight. He was trim. He moved with grace. He was more than a decade-and-a-half older than I was, and I was still running between five and six miles a day at that point five or six days a week, but I wouldn’t have wanted to mix it up with him. He was in better shape than most guys half his age. This was because he had discipline, an inner discipline that you can’t help but admire. As a professional, he had gone 166 three-minute rounds in the ring against opponents of lesser and greater skill and ability trying to knock his block off. He put in several thousand rounds in the gym training. He had risked, to be sure, his physical wellbeing every time he got into the ring. Still, he had the ability, the reflexes, to slip the punches headed his way, to dodge the damage others were intent on doing to him. He had given way better than he got. He remained intact. And when the time came that he was going to no longer profit by being a pugilist, he made a clean break of it and walked away. I did not come into his sphere until 47 years after he retired from boxing. Still, when I met him, he was a magnificent physical specimen and he had preserved the advantage that God had given him for more than seven decades.

He was no punch drunk palooka. He had his wits about him. I spent several hours Christmas Eve 2015 and as many hours again Christmas morning discussing with him life in America, as it was in that time before Donald Trump had come to be the dominant political force that defines everything around him. He knew the East Coast. He knew the West Coast. He appreciated the contrast of the Midwest with both. As a boxer, he had traveled to different venues to take on his opponents. He was opinionated but not intolerant of other ideas. He was nuanced in his observations. He did not condemn the Democrats for their ruination of the country nor demonize the Republicans for their approach. Neither did he see one side as offering a solution that was exclusively better than the nostrums of the other. He was articulate. He was neither profane nor vulgar. He had a generosity of soul and respect for others.

He had been beaten up by circumstance in a way that none of the 31 opponents in his 34 bouts had ever managed to inflict on him. In 2003, his wife of nearly 40 years, Helen, died. He survived her by two decades but was in a real sense cut off from the life he had known and lost.

I learned about Tony’s passing from my sister-in-law yesterday.

In the scheme of things, Tony and I didn’t really have a lot of interaction. It is hard for me to convey the degree of respect I had for him. I will try to express it in two ways.

First, as a journalist, I virtually never write in the first person. You can go back and examine nearly a half century of my newspaper articles and they are exclusively, as best as I can recall, written, to the limitation of my ability to do so, as third-person objective narratives. As you can see, gentle reader, I have dispensed with that and am writing this tribute to Tony as a first-person narrative.

Secondly, I can tell you that over the last few years, perhaps because all of those blows he had taken had begun to catch up with him or maybe simply through the ravages of age, Tony was beset with a slowly advancing dementia. That development provoked a spat among his six daughters – Audrey, Camille, Carol, Lisa, Rhonda and Tobey – as to which of them would get to care for him. I am told they eventually resolved that by agreeing to a schedule to rotate him among them.

How many of us will have our children competing to look after us when we no longer can?