By Mark Gutglueck

Dennis Hansberger, a central figure within the Redlands political and financial establishment who served 20 years on the San Bernardino Board of Supervisors over the course of nearly four decades and adroitly used the political revolving door to capitalize on his insider knowledge in the role of a lobbyist once he was out of elected office, has died.

Dennis Hansberger, a central figure within the Redlands political and financial establishment who served 20 years on the San Bernardino Board of Supervisors over the course of nearly four decades and adroitly used the political revolving door to capitalize on his insider knowledge in the role of a lobbyist once he was out of elected office, has died.

As must all mortals, Hansberger this week made his exit from this world, in his case peacefully and with members of his family near him. His last weeks, days, hours and minutes were spent in Redlands, the epicenter of the county’s old guard and old money, which, while Hansberger was yet one of its prime movers and most dynamic operators, gave way to the upstart Young Turks in Ontario, Rancho Cucamonga and Fontana who created an economic synergy that shifted the power balance to the west end of the county in the 1970s, 1980s 1990s and 2000s.

Hansberger came to social and political prominence within the context of the Redlands political machine, in no small part because of assistance from his father, Leroy, who had become a part of the East Valley Establishment in the generation prior to Dennis Hansberger’s rise to public life.

Despite having well-heeled and highly influential distant familial relations elsewhere in the country, Leroy Hansberger had as legitimate of a claim to being a self-made multimillionaire as anyone. Driven by an uncommon work ethic, he had come while he was still a child with his mother, Irma Lee Hansberger and stepfather Arthur Fagg, from Los Angeles where he was born in 1918, to Yuciapa, where his family worked a farm on Third Street. That farm initially consisted of a few cows, poultry and rabbits and mostly apple groves, which were eventually converted to peaches and plums and other crops when the coddling moth wreaked havoc on the farm’s apples.

From about the time he was 12, Leroy was functioning as the head of his family, doing a good half of the work on the farm. Even before he had graduated from Redlands High School in 1936, he had made a foray into the world of business outside the family farm, delivering groceries from Sawyer’s Market along with newspapers.

By the time he was 22, Leroy Hansberger owned his own trucking company, which had come about when he traded the car he was using to make deliveries for a truck. He used the proceeds from the trucking company to bootstrap himself up further, purchasing Tri-City Concrete and Tri-City Rock Company, located in Redlands. With the combined income from the trucking company, the rock company and the concrete company, he began purchasing property, at first an acre or two at a time, then larger and larger parcels. Among his purchases was the 240-acre El Dorado Ranch; the 140-acre Ford Apple Ranch in Yucaipa, which he bought from Fred Ford, along with another large spread Ford owned, the Snow-Line Orchards; and a substantial portion of the Martin Ranch in Yucaipa. Leroy Hansberger subdivided the latter property into the Rolling Hills Estates. Over the course of several decades, he owned over a thousand acres, much of which he developed either residentially or commercially. Other real estate holdings he had were spun off at a profit to others who developed them.

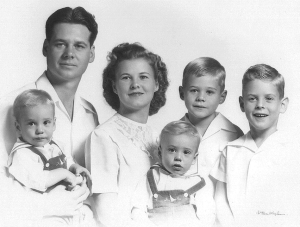

With his wife, Helen, Leroy Hansberger had four sons, all of whom were given names that started with the letter D: David, Dennis, Doug, and Don.

Hansberger came to social and political prominence within the context of the Redlands political machine, in no small part because of assistance from his father, Leroy, who had become a part of the East Valley Establishment in the generation prior to Dennis Hansberger’s rise to public life.

Despite having well-heeled and highly influential distant familial relations elsewhere in the country, Leroy Hansberger had as legitimate of a claim to being a self-made multimillionaire as anyone. Driven by an uncommon work ethic, he had come while he was still a child with his mother, Irma Lee Hansberger and stepfather Arthur Fagg, from Los Angeles where he was born in 1918, to Yuciapa, where his family worked a farm on Third Street. That farm initially consisted of a few cows, poultry and rabbits and mostly apple groves, which were eventually converted to peaches and plums and other crops when the coddling moth wreaked havoc on the farm’s apples.

From about the time he was 12, Leroy was functioning as the head of his family, doing a good half of the work on the farm. Even before he had graduated from Redlands High School in 1936, he had made a foray into the world of business outside the family farm, delivering groceries from Sawyer’s Market along with newspapers.

By the time he was 22, Leroy Hansberger owned his own trucking company, which had come about when he traded the car he was using to make deliveries for a truck. He used the proceeds from the trucking company to bootstrap himself up further, purchasing Tri-City Concrete and Tri-City Rock Company, located in Redlands. With the combined income from the trucking company, the rock company and the concrete company, he began purchasing property, at first an acre or two at a time, then larger and larger parcels. Among his purchases was the 240-acre El Dorado Ranch; the 140-acre Ford Apple Ranch in Yucaipa, which he bought from Fred Ford, along with another large spread Ford owned, the Snow-Line Orchards; and a substantial portion of the Martin Ranch in Yucaipa. Leroy Hansberger subdivided the latter property into the Rolling Hills Estates. Over the course of several decades, he owned over a thousand acres, much of which he developed either residentially or commercially. Other real estate holdings he had were spun off at a profit to others who developed them.

With his wife, Helen, Leroy Hansberger had four sons, all of whom were given names that started with the letter D: David, Dennis, Doug, and Don.

Dennis was born October 1, 1941 in Redlands. Seemingly determined to equal or surpass his father’s display of early initiative, while he was yet attending Redlands High School, from which he graduated in 1960, Dennis was working the night shift at Atlas RediMix Concrete Company in Colton. He remained employed with Atlas while he attended San Bernardino Valley College from 1960 to 1963. In 1964, he enrolled at the University of California at Riverside, studying geology, world literature and business administration. At that time he was employed with the Redlands School District, as a teacher’s assistance in a class for handicapped children at Crafton Elementary School. Late in 1964, his father hired him as the financial manager of the Tri-City Concrete Company.

Four years later, convinced by his father of the convergence between politics, government and business, Dennis applied for a position of authority in government. At that point, such an opportunity had presented itself when Wesley Break, a Redlands establishment institution unto himself and friend of Leroy Hansberger, chose not to seek reelection as Third District San Bernardino County supervisor, retiring after his sixth term in office and endorsing another element of the Redlands establishment who was also a Leroy Hansberger associate, Don Beckord, to succeed him. Rather than begin at the bottom rung in government, the younger Hansberger relied upon his father’s connections and he bypassed a good seventeen steps up the county pecking order, applying to become and being accepted as Beckord’s executive assistant and lead field representative. Dennis Hansberger over the next four years made himself intimately familiar with the ins-and-outs of San Bernardino County governance. When Beckord opted out of seeking reelection after serving a single term, from December 1968 until December 1972, Hansberger vied to succeed him, winning that election. He was 31 years old, making him, after Norman Taylor in 1855, Minor Cobb Tuttle in 1862, Robert McCoy in 1861 and John C. Turner in 1893, what was then the fifth youngest member of the board of supervisors in San Bernardino County history.

After just two years in office, in December 1974 at the age of 33, he was selected by his supervisorial colleagues, to serve as board chairman, making him what was then celebrated as the youngest chairman of the 58 boards of county supervisors in California, and the second youngest, after John C. Turner in 1895, board chairman in San Bernardino County history.

In 1980, after serving eight years on the board, the latter four with then-Fifth District Supervisor Robert Hammock, one of the most corrupt politicians in San Bernardino County history, and the latter two with then-Second District Supervisor Cal McElwain, whose self-interested voting decisions and political and personal associations with disreputable and unscrupulous personages and business interests cast discredit upon San Bernardino County and its governmental structure, Hansberger declined to seek reelection.

In short order, he formed Hansberger and Associates, a lobbying firm in which he front-ended for a host of businesses and entities which had project proposals before or were seeking contracts or franchises from local governmental entities. One initial success that Hansberger and Associates scored was when four ambulance service providers – Steve Dickmeyer, Don Reed, Homer Aerts and Terry Russ – who up until that time were in a cut-throat competition with one another for ambulance routes and franchises within the most urbanized portions of lower San Bernardino County, merged to become Mercy Ambulance Service. With Hansberger as both its strategist and representative, the company carried out a campaign of ruthlessly acing out its competitors through a combination of hefty political donations to city council members and members of the board of supervisors, retaining as the company’s legal counsel members of the law firms that employed many of the city attorneys where Mercy was seeking an exclusive ambulance franchise, inducing city councils to adopt ambulance ordinances ostensibly written to protect the public but which locked in Mercy’s operating advantages, and thereupon buying out or forcing out of business other ambulance companies in the area. Ultimately, Mercy, functioning within the pay-to-play atmosphere that had become the norm in San Bernardino County at both the county and municipal levels, established what was, if not a technical monopoly, then absolute dominance over the provision of ambulance service in the most populated, and therefore most lucrative, districts within the county’s 20,105-square mile expanse.

In relatively short order, Hansberger had established his reputation as a political fixer, someone who in advance arranged, in the backroom or across the table at a restaurant or in some other type of private meeting, how things were going to play out publicly when a governmental decision-making panel made its vote in public. Skillfully, Hansberger was able to convert the goodwill and influence some of his clients were achieving and obtaining with their large-scale political donations to officeholders into carryover goodwill and influence for his other clients. While the companies that hired Hansberger and Associates to represent them were not the only successful applicants for project approvals or the only competitors for county or city contracts or franchises, few elected officials who were recipients of substantial political donations from Hansberger and Associates’ clients were willing to vote against or make decisions contrary to the interests of those represented by Hansberger. The message to politicians all over San Bernardino County was clear: Support Dennis Hansberger in whatever he is advocating and you will receive sufficient political donations to sustain yourself in office; vote against what he advocates, and your political opponent in the next election will be provided with enough monetary support to ensure your removal from office. More than three decades after Hansberger had perfected this formula, he conceded that it was “distasteful, but that’s the way things get done in politics.”

The way Hansberger was operating was not without controversy at the time, and on occasion, his advocacy for a particular applicant for governmental approval triggered very close and always unwanted scrutiny of the applicant and the applicant’s proposal by a member of the decision-making panel who was offended by the casual political influence-purchasing ethos that Hansberger embodied. Such episodes were relatively rare, however. The standard response that Hansberger had formulated when he was confronted in this manner was to state that he could not understand why his communicant was so angry.

In 1996, after 16 years in the private sector, as the political gravitas of San Bernardino County was shifting away from the old money Redlands-based political establishment toward the new money West San Bernadino County political forces in Rancho Cucamonga, Ontario, Chino and Fontana, Hansberger, in what might be interpreted as an effort for the traditionalists in power in Redlands to reassert themselves over the political sphere in San Bernardino County, again took up the political gauntlet, running to replace the retiring Barbara Cram Riordan, another member of the Redlands old money political establishment who had held the Third District position for 13 years after initially being appointed to the post when David McKenna, who had succeeded Hansberger in 1980, was appointed county public defender.

Hansberger was elected, largely on the strength of backing by the rapidly-aging-and-fading but yet far-reaching Redlands power elite. Once again in office, Hansberger encountered a world that had changed in many respects from when he had previously been on the board. Most evident was that the Redlands power block, which at one point was so pervasive in its reach that it outweighed, outranked and could outspend the other four-fifths of the county and its presence on the board of supervisors, no longer held the sway it once did. Hansberger encountered, and was encountered by, board colleagues who were very much his equals in terms of political control and influence. One of the few means of leverage he possessed was the Republican affiliation he shared with the majority of the board’s members, as the Republican Party remained a significant player in the way in which governance manifested in San Bernardino County.

Still, there was another presence on the board that Hansberger had to contend with in the personage of Jerry Eaves, a labor union-affiliated Democrat who was both a former mayor of Rialto and a member of the California Assembly before he had somewhat inexplicably departed pre-term limit Sacramento to successfully run for Fifth District San Bernardino County supervisor when Bob Hammock, unsuccessfully, had sought to vault into Congress in 1992. Eaves, who was only marginally less dishonest, self-serving and corrupt than his predecessor as Fifth District supervisor, represented a formidable political presence on the board. Whereas Eaves had been at most a medium-sized fish in the Sacramento Lake, he was a virtual whale in the San Bernardino County pond. One strength Eaves had was that he had done favors for a number of state, national and international interests during his eight years in the California legislature, collecting chits along the way. Having returned to localized politics on a board where instead of lining up dozens of votes to achieve legislative goals he needed only two votes beyond his own to prevail, Eaves would call upon his donors from outside the Fifth District, outside San Bernardino County, indeed even outside of California or the United States to confer large donations on those he would designate to be the recipients of that largesse. In this way, Eaves was purchasing, when the stakes were high enough and he needed to, control over the board of supervisors to achieve his sometimes lofty and sometimes sordid, sometimes noble and sometimes ignominious, objectives.

As a consequence, Hansberger somewhat paradoxically given his 16-year role as an influence broker, found himself in the role of a political reformer, one of the minority members of the board of supervisors resisting special interests who were seeking to use their monetary reach to influence the county’s public policy in a way that would benefit a private interest to the detriment of the public at large. Ultimately, Hansberger would see his political stock rise when Eaves became enmeshed in a political corruption scandal and was forced from office upon being convicted.

While serving as supervisor, Hansberger served on a multitude of regional governmental adjunct and joint powers authorities and boards, and acceded to the presidency of the Southern California Association of Governments, the foremost regional planning authority in the southern part of the state, known by its acronym SCAG. He also received a gubernatorial appointment to serve on the California State Board of Mines and Geology.

Hansberger’s return to politics coincided with the break up of his first marriage. In 2000, Karen Gaio, an obstetrician-gynecologist who was 23 years Hansberger’s junior, had been elected to the Loma LInda City Council. Subsequently, her city council colleagues had appointed her mayor. Hansberger and Gaio encountered each other on governmental adjunct and joint powers authority boards in their capacities as supervisor and councilwoman/mayor. By 2001 they had entered into a personal relationship. In 2002, they married.

Hansberger’s role and reputation as a political reformer in the face of Eaves’ depredations carried across partisan lines when he stood up against the county being cozened into providing the flood control infrastructure for a massive development proposal on over 400 acres of what was considered undevelopable land in Upland which was crisscrossed with flood control easements and had traditionally been used for groundwater recharge. When Dan Richards, a prominent Republican who was a member of the new money Republican political faction on the county’s west side, sought to have the county defray a significant portion of the cost of supplying the Colonies at San Antonio residential and Colonies Crossroads commercial subdivisions’ drainage infrastructure, Hansberger consistently supported the county in administratively and legally opposing those requests. Ultimately, the county board of supervisors, over an opposing vote by Hansberger and Fifth District Supervisor Josie Gonzales, in November 2006, voted to settle litigation brought by Richards’ company, the Colonies Partners, over the county’s lack of cooperation in allowing the project to proceed. That settlement included a $102 million payout from the county to the Colonies Partners.

That was not the end of it, however, as Mike Ramos, himself a member of the Redlands Republican political establishment who had first been elected district attorney in 2002 with Hansberger’s support, had charges filed against Richards’ primary associate in the Colonies Partners, Jeff Burum, on charges that the Colonies Partners had used intimidation, extortion, blackmail and bribery to obtain the $102 million settlement. In addition to Burum, that prosecution extended to First District Supervisor Bill Postmus and Second District Supervisor Paul Biane, who voted in support of the settlement, as well as to Mark Kirk, the chief of staff to Fourth District Supervisor Gary Ovitt, who had likewise voted in favor of handing the $102 million in county money over to the Colonies Partners, and Jim Erwin, a one-time sheriff’s deputies union president who had assisted the Colonies Partners in its strategy to obtain the settlement. The prosecution of Postmus, who was convicted in the scheme, along with that of Burum, Biane, Kirk and Erwin, was undertaken in some measure on the strength of information provided by Hansberger to the district attorney’s office then under the authority of Ramos.

Well after Hansberger had left office following his second stint as supervisor, he was again in the public limelight when he was called as a witness in the case against Burum, Biane, Kirk and Erwin when it at last went to trial in 2017. Hansberger’s testimony was considered one of the key components to proving the case the prosecution had but together against the defendants, one which in significant measure hinged on the use of political influence – what the prosecution insisted was tantamount to bribery – in obtaining the $102 settlement. As it would turn out, however, the use of Hansberger as a witness in the case proved problematic. Hansberger’s own reputation as a political fixer who had arranged for the provision of large amounts of cash to politicians to gain their support for his clients’ projects, contracts and franchises undercut the prosecution’s case. Burum, Biane and Kirk were acquitted and the jury hearing the matter against Erwin was unable to reach a verdict.

A complicating issue during Hansberger’s second tenure as supervisor was the bark beetle infestation in the San Bernardino Mountains. In 1967, the Lake Arrowhead Corporation had merged with lumber giant Boise-Cascade, whose CEO, Robert Hansberger, was a distant relation to Dennis Hansberger. Boise-Cascade, after its Lake Arrowhead acquisition, had continued to clear forest property where it could for the purpose of subdividing properties and developing residential tracts. In 1971, Boise-Cascade had sold most of its Lake Arrowhead holdings to a consortium out of Chicago, but then reacquired the property as the result of a foreclosure. By the late 1970s, Boise-Cascade had divested itself of much or most of its Lake Arrowhead holdings. By the time of Dennis Hansberger’s second tour as third District supervisor, his father had acquired a good deal of property in the San Bernardino Mountains. Among a cross section of mountain residents, there was concern – rightly or wrongly – that from his position as a member of the board of supervisors, Dennis Hansberger was going to use the bark beetle infestation to engage in the wholesale destruction of swathes of the forest to allow the property there to be developed.

At certain points during his second round as supervisor, Hansberger was dogged by charges that his chief of staff, Jim Foster, was using his position of authority to enrich himself, as when he purchased a piece of what the county had deemed to be surplus property in Redlands. Foster was also suspected of steering business to his wife’s company, based upon his county influence. Eventually, Hansberger was obliged to shed Foster as his chief of staff.

In 2008, as Hansberger was nearing the completion of his third term in his second go-round on the board of supervisors and his fifth term overall, the political forces on the west side of the county, including those affiliated with the Colonies Partners, moved to derail his political career. Without major fanfare and doing so in a well-timed manner which essentially prevented Hansberger from knowing what was afoot until it was too late for him to effectively react to counter the intensive campaign against him, those focused on his removal vectored their support to then-San Bernardino City Councilman Neil Derry, who outpolled Hansberger in that year’s June primary, a head-to-head contest in which Derry prevailed by the relatively narrow margin of 22,567 votes or 51.89 percent to Hansberger’s 20,926 or 48.11 percent.

Hansberger’s political career was over, but he managed to have something of the last laugh, or perhaps, two last laughs. In April 2011, Hansberger was able to have Mike Ramos, the district attorney with whom he remained closely associated, charge Derry with one felony count of perjury, one felony count of filing a false document and one misdemeanor count of failing to report a campaign contribution properly, stemming from a $5,000 political contribution to Derry’s 2008 campaign that had originated as a $10,000 check from developer Arnold Stubblefield, but which was, according to Ramos, “laundered” through a political action committee controlled by Bill Postmus, who kept $5,000 of the money Stubblefield provided for himself. Ultimately, Derry pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor count in return for the two felonies being dismissed. Thereafter, Hansberger convinced James Ramos, the independently wealthy chairman of the San Manuel Indian Tribe, who reportedly netted $18,000 per day from the tribe’s casino operation, to run against Derry in the 2012 election. Hansberger crossed party lines to promote Ramos, a Democrat, over Derry, a Republican. To Hansberger’s immense satisfaction, Ramos defeated Derry.

In 2018, when James Ramos was elected to the California Assembly in the middle of his second term as Third District supervisor, necessitating that he resign to take the state legislative office, Hansberger was one of 48 applicants seeking the appointment to replace Ramos. He was one of 13 of the 48 chosen to be interviewed by the board of supervisors before a selection was made, which ultimately fell to former Yucca Valley Councilwoman Dawn Rowe.

Hansberger cited as his proudest accomplishments in public office the construction of the Seven Oaks Dam at the headwaters of the Santa Ana River in the foothills of the San Bernardino Mountains near Highland and Mentone; his contribution with regard to the establishment of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, of which he was a founding member and among its first directors; the completion of the San Timoteo Creek Project; the expansion of the San Bernardino County Museum; the expansion of the San Bernardino County Regional Park System, most particularly Yucaipa Regional Park; ongoing efforts against blight, and his role in securing federal funding for that effort; and the restoration of the public’s trust in the integrity of local government.

At the time of his death, he was on the board of the San Bernardino County Museum.

He died Wednesday, at the age of 78, less than a month after he was diagnosed as suffering from pancreatic cancer. A report held that his wife, Karen Gaio Hansberger, his sons Martin, Mark and Matthew, and his daughter Marshand were present at the time of his passage.

Assemblyman James Ramos said, “My family and I express our deepest condolences to the family of Chairperson Dennis Hansberger. Our thoughts and prayers are with them. Among my fondest memories of Dennis are the many times we spent talking about the history of San Bernardino County, often from my perspective as chairperson of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. Dennis was also a valued supporter who encouraged me to run for the county board of supervisors, and was proud when I became chairperson of the board. He will always serve as a model for me because of his integrity and service to constituents. Dennis carries a special place in my life.”

“Dennis was a kind and thoughtful leader who truly cared about improving the lives of the people he served,” said current Third District Supervisor Dawn Rowe. “The role he played in shaping the future of our county cannot be overstated. Our thoughts and prayers go out to his wife, Karen, and his entire family.”

Board of Supervisors Chairman Curt Hagman said, “Dennis is a legendary figure in the history of San Bernardino County. We will remember him as a fearless and vocal advocate for ethical, open and intelligent government who guided our county through some of its most challenging times.”

Supervisor Josie Gonzales characterized Hansberger as a “San Bernardino County icon who was always steadfast in his convictions and who valued the truth above his own popularity. He was a maverick… never afraid to say what needed to be said and bring up new ideas and fresh approaches. He was an honorable man.”