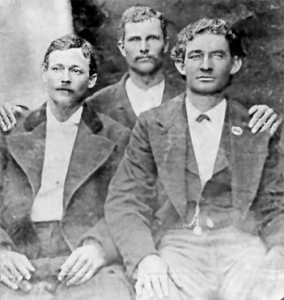

John D. Glenn (left) and Silas S. Glenn Jr. (center) and Robert (right) A fourth brother, “Jerry”, died in a gunfight in Tehachapi in 1878. (Photo from the Virginia R. Harshman Collection)

By Mark Gutglueck

The Glenn family, consisting of Silas Glenn and his wife Mourning and their daughter and four sons, were early settlers in Lytle Creek. Silas and his wife moved from Texas to El Monte to raise their family in California, where conscription into the Confederate Army would not take place. In 1866, they moved to Lytle Creek, where Silas created a ranch.

1878 was a rough year for Mourning Glenn, as she suffered through the deaths of her husband, Silas Glenn, Sr., and her son, Jeremiah, who was killed in a gun battle. In the years thereafter, it was all she could do to maintain the Glenn Ranch in Lytle Creek Canyon. The widow was not without resources, and she was able to make ends meet by welcoming asthma and consumption patients at the ranch as boarders. As the situation suggests, she offered them comfort in a place where the climate might prove a curative to their maladies.

Over the next decade, Mrs. Glenn received little in the way of assistance from her son, Silas, Jr., who was engaged in working gold claims further up the canyon he had originally filed in 1874, although he lived at the ranch off and on.

By the late 1880s, Mrs. Glenn was in need of ever more assistance, and she turned to her daughter, Ellen, who had married James Applewhite, hoping to persuade her to relocate back to the ranch in Lytle Creek and provide her with the assistance she needed to keep the ranch from falling by the wayside. In 1889, at the age of 75, she wrote her daughter a letter with a formal invitation to return home with her husband and take on the management of the ranch. She was particularly looking forward to having her son-in-law, James Applewhite, present to handle the rougher duties running a ranch entailed. In an August letter she again wrote to her daughter, indicating that she had her hands full in dealing with those camping and taking day tours of the ranch, saying she was looking forward to the arrival of Ellen and her husband.

In the spring of 1890, Ellen and James Applewhite arrived at the ranch and took up residence there. And while Silas, Jr. and his brother John had long taken for granted that the ranch would be a part of their inheritance, they had been less than diligent with regard to looking after it or their mother. With the arrival of their brother-in-law, both grew alarmed that this meant James Applewhite was moving in on what they assumed was rightfully theirs and that they were being cut off at the pass for their piece of the canyon.

At that point, Silas and John had not been absent from the Glenn Ranch and Lytle Creek altogether, but they were rarely around, having been herding cattle in the valley.

Contemporary newspaper accounts paint a somewhat deprecating picture of the two brothers, intimating that they were, in the words of Lytle Creek historian Virginia R. Harshman, “generally considered worthless and shiftless.” Conversely, chroniclers of the time had a somewhat higher regard for their brother, Robert, who was making a name for himself in Tehachapi, and enjoyed what Harshman characterized as “an excellent reputation.”

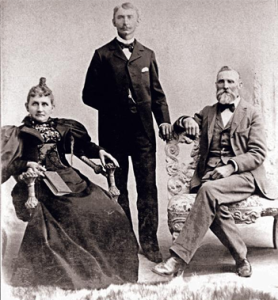

Ellen Applewhite (nee Glenn), left; James Oliver “Ollie” Applewhite, the sone of James and Ellen Applewhite, center; James M. Applewhite, right (Photo from the Virginia R. Harshman Collection)

In addition to his suspicion that his brother-in-law and his sister were in the process of usurping his inheritance, John Glenn had grounds for a further animus toward them. In November 1889, his wife, Maude, had left him to return to live with her parents. John believed she had done so at least in part because of the counsel of his 27 year-old nephew, Ollie Applewhite, the son of Ellen and James Applewhite.

On Friday June 23, 1893, John and Silas, Jr had returned to the ranch, ready, legend has it, to settle the matter with regard to their brother-in-law encroaching on what they felt was theirs. According to some, they had come to even the score with Ollie Applewhite for moving in on John’s wife. If their plan had been to ambush Ollie at dusk when he returned home for the weekend from his job in the valley, that plan was frustrated when Ollie waited until Saturday morning to return in broad daylight. James Applewhite, alarmed by the Glenns’ demeanor, behavior and loose talk, left the ranch very early to meet his son on his way into Lytle Creek and forewarn him of what might lay in store for him.

Sometime around 10 a.m. on Saturday June 24, 1893, with John and Silas, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Applewhite and Ollie outside of one of the ranch’s dwellings, one of the Glenn brothers became accusative and insulting toward Ollie, who dismissed what was being said by his uncle, telling him he wanted to hear no more. John Glenn escalated the accusatory palaver to threats. James Applewhite told his brothers-in-law that he could see they were itching for a fight, and that he did not want there to be any hostilities. Nevertheless, he said, if they were determined to mix things up, there was going to be trouble. He then walked toward one of the ranch houses, which was some 120 feet from where he had just had the testy exchange with John and Silas. He would later testify that he believed he might be shot in the back as he made this tension-filled walk. At the house, he retrieved his shotgun from where he kept it at the ready behind the dining room door. He went to the other side of the house and out another door to another ranch house some 180 feet distant, where he positioned himself on the porch. The others, having spotted him, began approaching him. Ellen, sensing things were moving toward an unwanted confrontation, importuned her brothers to stop. They continued on. At a point somewhere in between the two houses, one of the brothers remarked that it would be best to “do up” the son before they took on their brother-in-law. As John drew his revolver, Ollie drew his and blasted his uncle John, reportedly firing a single shot which hit him in the temple, killing him instantly. At the same moment, James Applewhite discharged a single round of buckshot, three pellets of which struck Silas, dropping him. Silas, still alive, was taken into one of the houses while Ollie headed off directly to Cajon, to the closest telegraph station. There he telegraphed Colton to reach Dr. Daniels, who formerly lived in Lytle Canyon and was the Glenn family doctor. Ollie Applewhite rendezvoused with Deputy Sheriff Whiteman in Cajon after sending the electric dispatch, surrendered to him and they both returned to the Glenn Ranch. Whiteman found John’s weapon in his hand and the gun belonging to Silas under his coat. Both were cocked but had not been fired.

Silas Glenn hung on for more than a day-and-a-half, but expired at 6 a.m. on Monday June 26. Before he died, Silas dictated and then affixed his signature to a will bequeathing his 160 acres and water rights to his mother, to an 18-year-old girl in Cajon, and to Dr. Daniels. Among his last words was his pronouncement that he was sorry for what had happened.

The coroner’s inquest over John’s death concluded Ollie Applewhite had acted in self defense. But his father, fearing reprisals if the matter was not settled entirely in a court of law, insisted that Ollie stand trial. After Silas died, both father and son were taken to San Bernardino, but were not subjected to the ignominy of being housed in the jail. Ellen went with them, and they stayed at King House, under a type of house arrest supervised by a deputy.

The trial had its dramatic moments. Mrs. Mourning Glenn testified that she had seen Ollie, her grand son, and Maude Glenn, her daughter in law and John’s wife, engaged in an animated conversation “like a couple sparking.” And, she said they had gone to three dances together.

In his testimony, James Applewhite laid the blame for the events leading up to the shooting at his mother-in-law’s feet, saying she had stirred things up with her sons. He said he did not believe she was in full control of her senses and had acted irresponsibly.

Father and son were acquitted.

John Glenn’s share of the ranch went to his estranged wife, Maude (Hazard) Glenn.

Mourning Glenn sold the portion of the Glenn Ranch under her control to James Applewhite and left for Tehachapi to live with her son, Robert.